2025 Inequality Landscape

View the report as a PDF

View the 2025 report background data

Data at a glance – charts from this report with most recent (updated monthly) data (available for download) can be accessed here

Download a replication file to guide reproduction of analysis of data obtained from the UK Data Service using Stata here

Foreword

The Health Foundation is proud to support the Scottish Health Equity Research Unit (SHERU), an independent policy research initiative rooted in Scotland. The team brings together socio-economic and public health expertise and experience from within and outside government to inform the action and collaboration needed to improve health and reduce inequalities – an ambition that remains as urgent as ever. They are strengthening independent voice, scrutiny and analysis in Scottish policy debates and building a stronger evidence base to drive more effective policy implementation.

This second annual report 2025 Inequality Landscape: Health and Socio-economic Inequality in Scotland, offers a timely and important contribution to that end. It can help inform policy and delivery at a time of emergence from successive crises – and debate ahead of the coming Scottish elections.

The report highlights some small signs of promise – particularly in reducing child poverty and narrowing the educational attainment gap. However, it also makes clear that there has been either little meaningful change in respect to health outcomes and many of the other building blocks of health – factors like employment and housing that shape those outcomes. While many of these problems are recognised and well formulated policy strategies and frameworks exist to support progress, the report’s analysis makes clear that without more effective delivery health inequalities will remain entrenched.

One of the most striking insights from the report is the persistent policy blind spot affecting a subset of younger men at risk of dying from drugs, alcohol or suicide. Too often help comes too late, at a time of crises instead of when issues start to emerge and can be more easily remedied. This failure in prevention is most starkly reflected in Scotland’s high and unequal rates of drug-related deaths – a tragedy that continues to expose deep-rooted structural inequalities.

Drawing on international examples of successful joined-up approaches and stakeholder perspectives of the efficacy of joined-up working in Scotland, the report proposes a clear framework to embed collaboration in policy implementation. It is one with prevention at its heart – a cross-government and cross-sectoral approach breaking down directorate boundaries at the centre and enhancing partnership with, and between, local authorities, agencies and the third sector on the ground.

Fiscal pressures and a growing demographic make it more important than ever to make an efficient use of limited resources and deliver on preventative public service reform. Whoever is elected in 2026 must commit to the action needed to improve health and reduce inequalities and be bold in making it happen. More of the same will not be enough.

David Finch is Assistant Director at the Health Foundation.

Executive Summary

This is the second annual report from the Health Foundation funded Scottish Health Equity Research Unit (SHERU). This year we have split the report into two sections:

Part 1 provides a stock-take of key data that capture health inequality trends and the underpinning socio-economic conditions that shape population health in Scotland.

Part 2 offers a deep dive into deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide and highlights young adult men experiencing socio-economic deprivation as a population group at high risk of these preventable deaths.

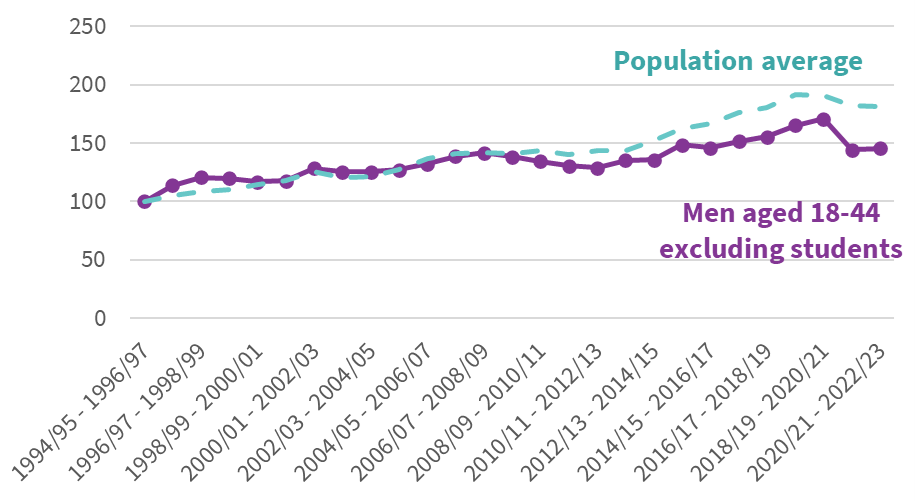

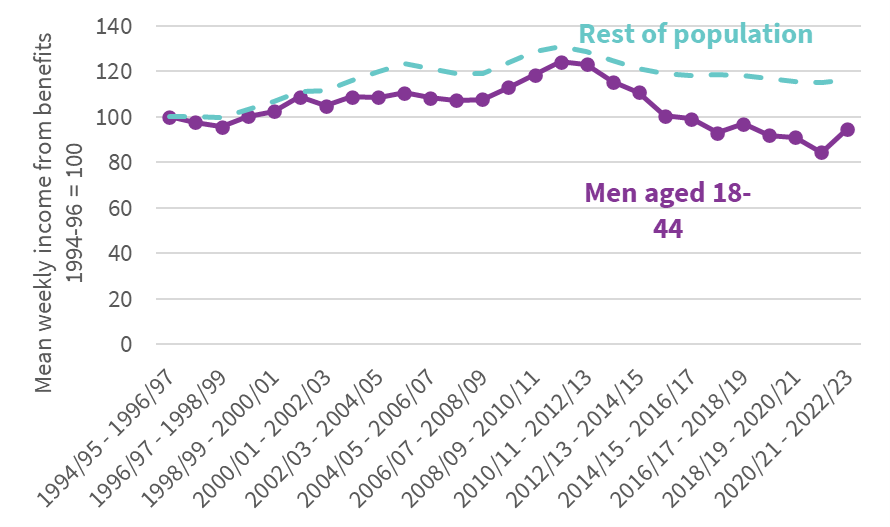

Overall, this report suggests there have been modest gains in some living-standards, including some hopeful signs of reductions in child poverty, but this is set against persistent, and in places deepening, structural inequalities that continue to drive poor health. Focusing on average outcomes paints a picture of men in Scotland doing relatively well but this obscures a subset of young adult men facing multiple socio-economic challenges who are at high risk of early, preventable deaths.

1. Progress on key trends: what changed this year?

Life expectancy & mortality: Both life expectancy and median income ticked up slightly from pandemic lows, but pre-pandemic stagnation looms large; inequality in key health indicators remains pronounced and shows, at best, only marginal narrowing.

Incomes & poverty: Median household income was higher in 2021–2024 than in 2020–2023 for most groups; pensioners were the exception. Methodological improvements now better capture the Scottish Child Payment, with early signs of child-poverty reduction. However, families with three or more children, households with disabled members, and households in rural areas are not seeing the same gains, and interim child poverty targets were not met.

Housing & homelessness: Homelessness applications dipped slightly in 2024–25, despite an overall upward trend in recent years, with temporary accommodation rising to unprecedented levels amid evidence of overcrowding, disrepair, and safety concerns. Targets for affordable homes remain a long way from being met in the context of what the Scottish Government has declared is a housing emergency. Damp/condensation and mould have increased in rented sectors and, while new laws should strengthen social-landlord duties, similar obligations are not yet planned for private renting.

Education & early years: The gap in developmental concerns at 27–30 months narrowed slightly over the last year but remains wide. School attainment gaps show limited improvement, while other indicators of childhood inequality remain stubbornly high. Attendance gaps persist, with higher levels of disengagement among disadvantaged pupils further reinforcing inequalities. In 2025, higher education participation rates for the 20% least and most deprived remained largely unchanged from the previous year, despite a slight widening of the gap.

Labour market & earnings: Survey quality issues mean there is some uncertainty as to whether economic inactivity is increasing to the degree that the statistics imply, which leaves policymakers struggling to make evidence-based decisions. Earnings data indicate small real-terms gains at the bottom and middle and declines at the top decile, narrowing, but not closing, the gap. Qualitative accounts highlight the need for tailored approaches to support people with health issues to stay in work.

Headline message: modest improvements in incomes and some child-poverty measures are not yet translating into material reductions in health inequality. Structural drivers – housing insecurity and quality, working conditions, and the long shadow of austerity – continue to shape outcomes.

2. Young adult men and preventable deaths

Scotland’s rates of drug-related deaths, alcohol-specific deaths and deaths from suicide remain the highest in the UK, with drug misuse mortality among the highest in Western Europe; around 70% of deaths across these causes were among men in 2023. The burden is concentrated in the most deprived communities and contributes to Scotland’s stark male life-expectancy gap (13+ years between the most and least deprived).

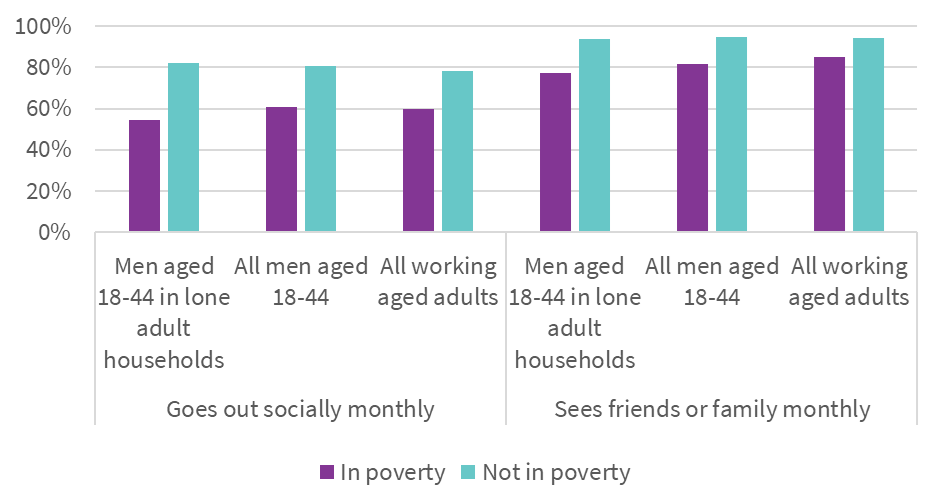

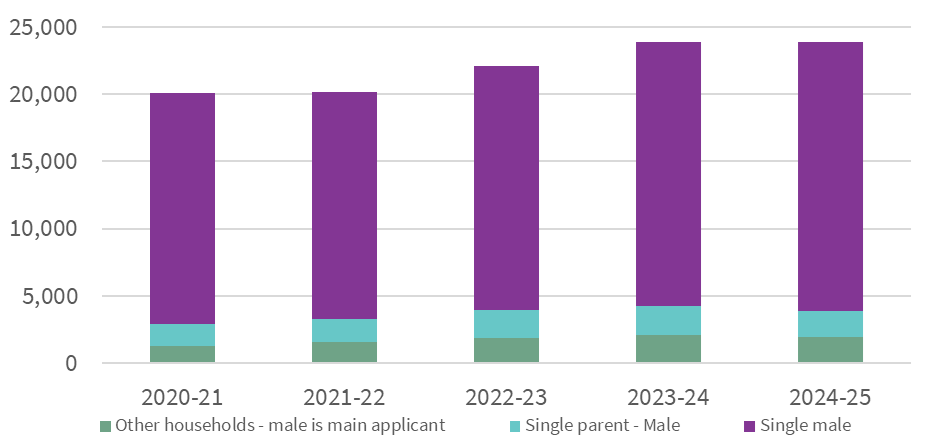

The report argues that young adult men at heightened risk are a policy ‘blind spot’: while they often ‘average’ well on income and employment, a subset experience compounding exclusion across work, housing, justice and mental health. Contact points – homelessness presentations, police/justice interactions, or A&E – typically occur after crises emerge, missing the preventative ambition of Scottish policy.

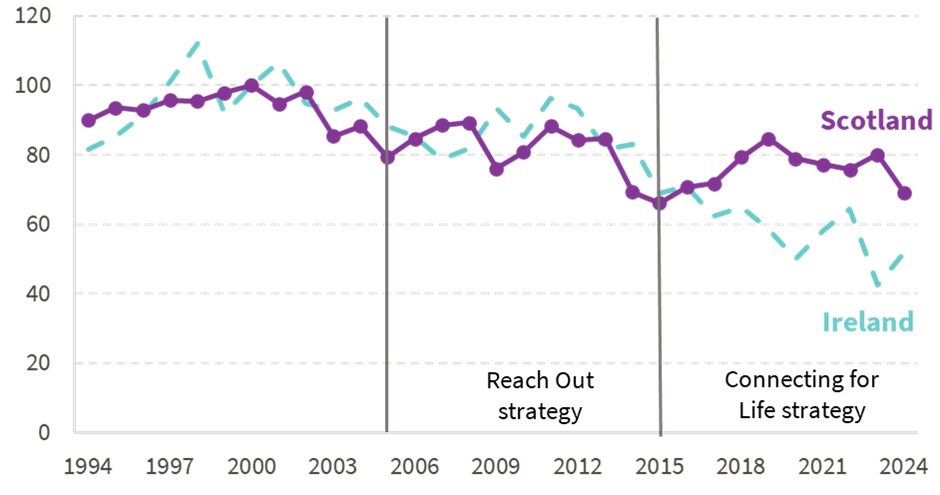

Two international examples of prevention: Ireland’s cross-government suicide-prevention governance strategy and Iceland’s community-led prevention model both demonstrate what is possible when national coordination, data, and local delivery align. The immediate challenges for Scotland are to: (1) strengthen the evidence base to track at-risk trajectories across systems; and (2) create robust, cross-sector governance so prevention is embedded in national policy and budgets, with a strong focus on delivery and implementation. Taken together, these examples suggest that Scotland will only deliver its long-standing ambition of prioritising prevention by improving cross-sector collaboration and tackling fragmentation between local and national bodies.

Overall conclusion: Scotland has begun to stabilise some indicators of living-standards but average trends obscure the fact that progress is not evenly distributed. As we show in Part 2, some young adult men facing disadvantage are at high risk of preventable deaths and yet seem to constitute a policy ‘blind spot’. A more joined-up, preventative approach to housing, income security, work quality and early intervention is urgently needed to tackle health inequalities. The path forward requires both targeted upstream investment and governance mechanisms to ensure that joined-up policy approaches are effectively implemented. Without these changes, the Scottish Government cannot credibly drive the action needed for long-term progress.

Introduction

This report is an annual publication that follows SHERU’s 2024 Inequality Landscape: Health and Socio-economic Divides in Scotland (1). Last year, we looked at a range of indicators covering household income, employment, education, and housing, all of which are socio-economic determinants of health. Understanding inequalities within these socio-economic indicators is critical to understanding the state of health inequalities in Scotland, which has some of the most extreme differences in key health outcomes in Western Europe (2).

We also explored how these inequalities have changed over time. A series of previous Health Foundation funded reports looked at developments in health and socio-economic inequality, beginning with Scottish devolution in 1999 and ending in the pre-pandemic period in 2019. Our 2024 report focused on 2019-2023, giving us a sense of how health and socio-economic inequalities have changed during and immediately after the pandemic.

Our key findings were concerning. Throughout the 2010s, Scotland experienced a stagnation in both health outcomes and living standards. The pandemic brought a period of extreme volatility, with sharp improvements in some areas but severe deterioration in others. In its aftermath, many indicators began to revert to the underlying trends established since 2010, with no evidence that the aftermath of the pandemic looked any better than the stagnation that came before. An even more concerning finding was that some health and socio-economic indicators had noticeably worsened post-pandemic, with deepening inequality.

It will be many years before the full effects of the pandemic can be quantified in data. However, each year on from the pandemic gives us an opportunity to take stock and better understand how Scotland is faring. Differences between two years will often be small, but each year gives us a slightly better understanding of the effects of policy changes, which bring opportunities for policymakers to learn lessons that can inform future policy plans, and also allows us to spot possible emerging trends.

The policy context has shifted a little in the past year, with a renewed focus from the Scottish Government on health inequalities via the new Population Health Framework (3). Whilst strong on evidence and aspiration, the implementation of the framework will need to fulfil its ambition of cross-government working to address the upstream determinants of health inequalities. Shortly afterwards, the Scottish Government also published its Public Service Reform Strategy. This outlines some of the necessary steps required for Scotland to achieve public sector accountability that enables “collaboration, and the investment of resources and capacity in collectively achieving priority outcomes” (4). A challenging fiscal backdrop remains and while this can make structural reforms more challenging, the financial sustainability of the NHS has also come under scrutiny in the past year (5), underlining the necessity of reducing demand through improving health via upstream, preventative measures.

This year’s report is divided into two parts. In Part 1, we explore how these outcomes have developed over the last year, examining any changes in the policy space along with any new studies or commentaries that help shine a light on underlying trends.

This year, key findings include:

- Relatively little change in inequalities in health outcomes, when comparing the most and least deprived areas in Scotland for key indicators where new data is available

- Small improvements in incomes and indications of a shift in child poverty rates for most households with children, following the roll-out of the Scottish Child Payment

- Decreases in affordable home building, alongside increases in homelessness applications

Our last report also discussed a well-reported trend: people in Scotland are more likely to die from drugs (6), alcohol (7), or suicide (8) than any other nation in the United Kingdom, and Scotland has the highest drug related mortality rate in Western Europe. In 2023, all three mortality rates increased compared to 2022. While we won’t have 2024 data in time to update for all three mortality rates for this report’s publication, in Part 2 of the report we have explored data on the socio-economic conditions of the people most at risk of these extreme outcomes: young adult men living in the most deprived areas of Scotland.

Scotland has the lowest life expectancy in Western Europe, and men in deprived areas have a life expectancy that is more than 13 years shorter than men in the least deprived areas (4). However, on average, men aged 18-44 are doing well: they earn more and have lower rates of poverty than other age and gender cohorts. They also have the highest rates of employment and are more qualified than ever before. Because of how well men fare on average, the subset of men living in poor socio-economic situations who are most at risk of deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide are often overlooked in economic and social policy considerations. It is not until they are already facing crises, such homelessness, criminal activity, addiction or mental health breakdown that the state usually intervenes. Likewise, research on the lives of men in this age group is relatively limited up until the point of crisis intervention.

We close by looking at some international examples that Scotland can learn from, showcasing two examples of preventative policy approaches from other countries which aimed to reduce harmful substance use and suicide.

Together, the two parts of this year’s report offer a deeper understanding of the evolving landscape of inequality in Scotland, both in terms of national trends and the experiences of a specific population group – young adult men – who are often missed in mainstream analysis. As inequalities persist and, in some cases, deepen, the need for timely, data-informed, and joined-up action becomes ever more urgent.

Part 1: Progress on key trends

Progress on key trends

As was the case in SHERU’s 2024 Inequality Landscape, we start with two high level indicators that give a snapshot of health and socio-economic outcomes: life expectancy and median income. Both indicators show a similar small improvement in the latest data, seemingly recovering slightly from a pandemic related downturn in the preceding years.

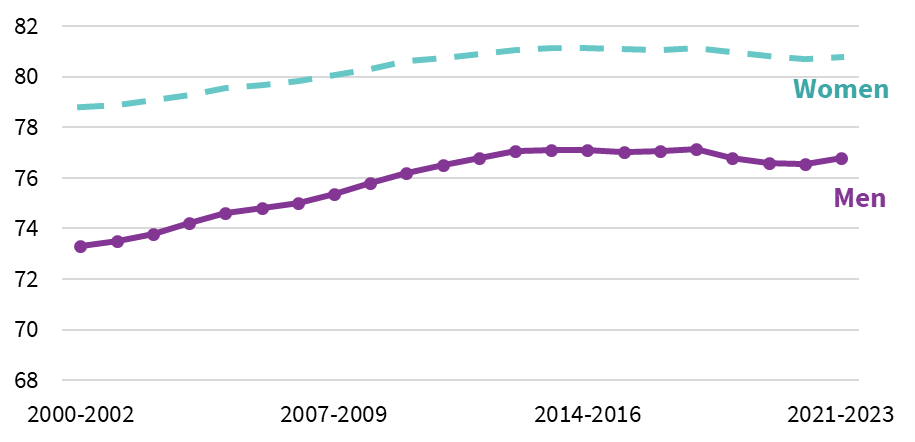

Figure 1.1 Life expectancy at birth, in years

Source: National Records of Scotland, 2024 (9)

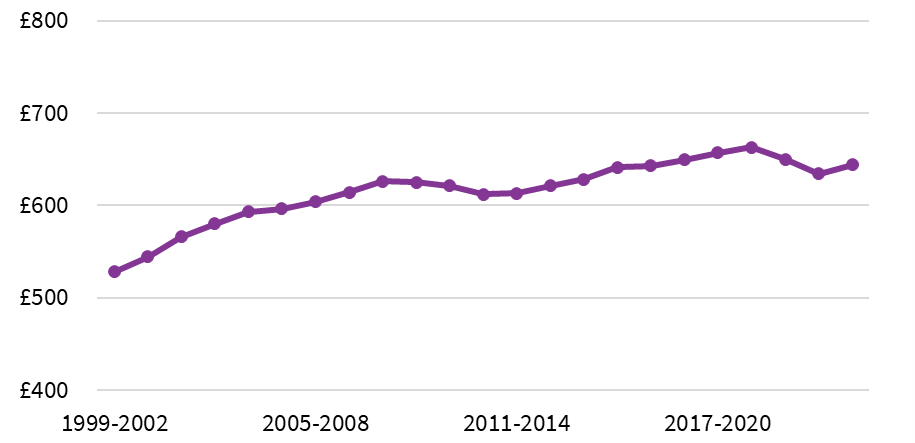

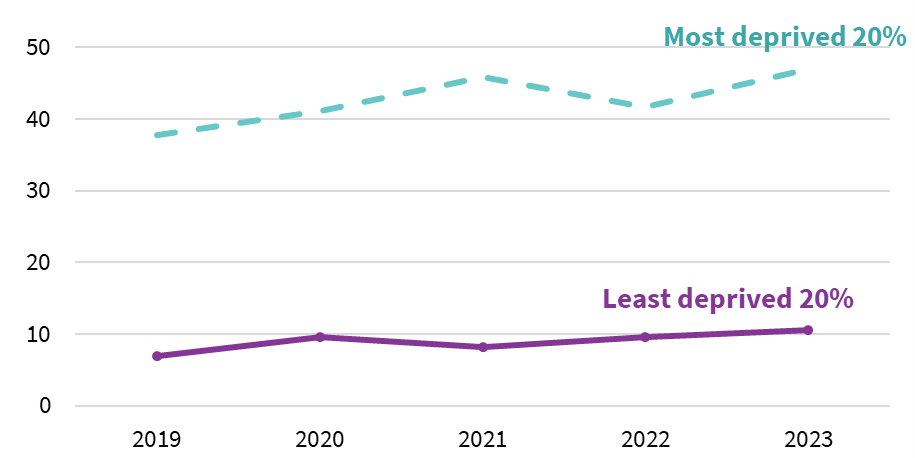

Figure 1.2 Median weekly household incomes (in 2023-24 prices) before housing costs

Source: Scottish Government, 2025 (10)

Pre-pandemic, there was evidence of a flattening of the long-run trend of improvement in life expectancy.

Mirroring life expectancy, the long-term rise in median income flattened after the 2008 financial crisis and during the 2010s, a period marked by UK Government austerity policies that reduced public spending. It is widely accepted that this austerity period through the 2010s contributed to the subsequent decline in life expectancy and left public services in a fragile state going into the pandemic (2). Ongoing fiscal restrictions on public spending have made public service recovery challenging, especially in the face of increasing demands (11,12). The ongoing fragility of many public services in Scotland remains a stark challenge for efforts to reduce health inequalities.

Several studies published in 2024 and 2025 have added to the growing evidence base suggesting that the scale of life expectancy declines during the pandemic was linked to the pre-pandemic slowdown in life expectancy improvements (13–15). Examining trends across European countries, a Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors study found that nations that had made the most progress in improving population health pre-Covid were able to maintain those improvements through the pandemic (14). Sweden, Norway and Ireland even recorded improvements in mortality rates between 2019 and 2021, with improvements in mortality rates for non-Covid conditions outweighing the impact of deaths related to respiratory causes. By contrast, countries that had seen more limited reductions in mortality, particularly from cardiovascular disease and cancers, between 2011 and 2019 experienced little or no progress in reducing deaths from non-Covid causes between 2019-2021. Scotland and Greece were singled out as the worst performing in this regard with no notable reductions in mortality from non-Covid causes over the period. The impact of austerity was given as a possible cause of the relatively poor performance of the UK nations, Greece and Italy on broader mortality rates in the run-up to and during the pandemic.

New analysis released in the last year also includes a systematic review across high-income countries (16) and a book by Glasgow based academics David Walsh and Gerry McCartney that provides an in-depth assessment of UK experiences compared to other high-income countries (15). Both conclude that austerity led to negative health outcomes and that the UK was particularly negatively affected. Walsh and Macartney’s book attributes this to the fact austerity policies in the UK disproportionally impacted the most vulnerable populations, including those on low incomes. Their analysis identifies mental health as a key pathway connecting austerity policies to poor health outcomes. This aligns with earlier work published by VOX, a national mental health service user led organisation based within Scotland, which cites multiple examples of people describing how cuts to public services during the austerity years exacerbated their mental health challenges. For example:

“I’ve gone from someone who lived/worked full time despite an underlying mental health condition, to someone unable to work, unable to access health care (refused) or community support (When I have tried I’m told I am too unwell and need health care first) reliant on social care. The social care I’m allocated is unable to meet my needs. The Service I have found helpful is closing due to council cuts. I can’t see any hope at all; I’ve tried to keep going despite deteriorating health, but the removal of hope by both health care, social care cuts, benefit freezes leave me just functioning in survival mode and [I am] looking forward to the morning when I don’t wake up and don’t have to suffer anymore.”

VOX, 2017 (17)

A couple of recent studies provide further evidence of the mechanisms and pathways linking austerity to poorer health outcomes, placing a similarly strong emphasis on mental health. Mason et al. (2024) found that housing payment difficulties, worsened by austerity, raised the risk of mental health disorders and sleep disturbances, especially among renters, young people, and low-income families (18). While Taylor et al. (2024) linked increased foodbank use to welfare cuts, sanctions, and benefit delays, with users reporting worsened mental and physical health due to stress, stigma, and poor nutrition (19). For further evidence of the links between austerity and health outcomes, see SHERU’s June 2025 Spotlight on Research: Exploring the Health Impacts of Austerity (20).

High Level Indicators of Health Inequality

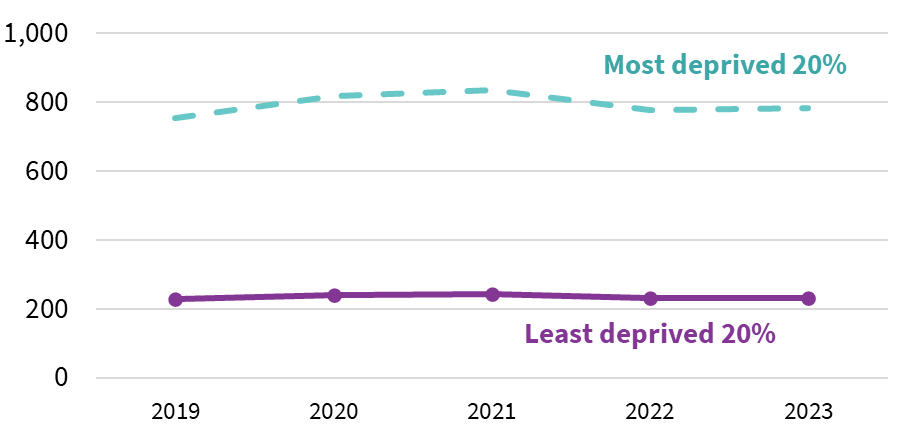

Delays in the publishing of indicators on deaths related to alcohol mean we cannot provide an update on all indicators included in our 2024 report. However, we do have new data on a number of indicators, including early mortality. This shows that, after a narrowing of the early mortality gap between most and least deprived areas in 2022, there was no change in 2023 (Figure 1.3).

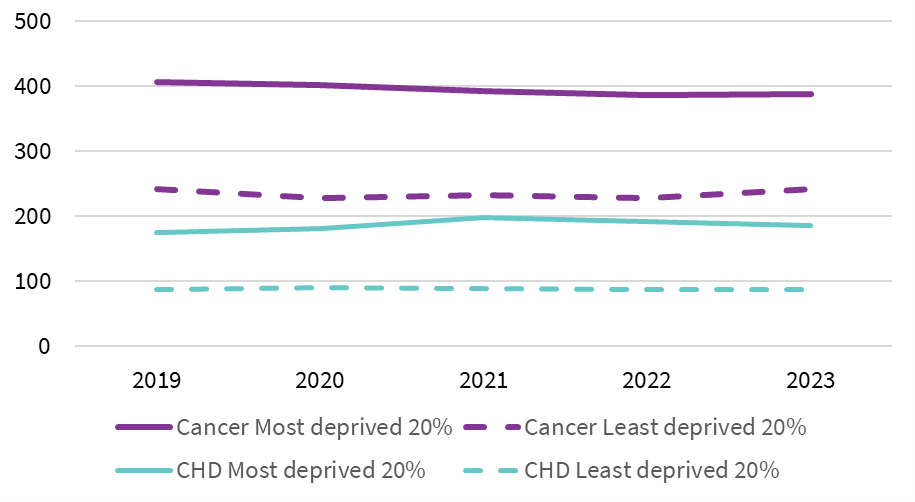

If we compare the most and least deprived areas of Scotland, the most recent (2023) data shows that there has been a slight narrowing of the gap in deaths from coronary heart disease and cancer (the most common causes of death in Scotland) (Figure 1.4) (21).

For cancer, the improvement is unfortunately due to an increase in mortality rates in the least deprived areas. In contrast, for CHD, it reflects a reduction in mortality rates in the most deprived areas, with no change in the least deprived.

Reviews of international evidence, and new comparative research, find that risk factors for cancer and cardiovascular disease tend to be higher in lower-income groups and in groups with less education (14,22,23). Common risk factors for cancer and heart disease include smoking, low levels of physical activity, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and being overweight and obesity. Several countries, including Scotland, have managed to reduce some of these risk factors at population level in recent decades but large inequalities remain (24).

Figure 1.3 Early mortality rate (under 75) (age-sex standardised rate per 100,000 population)

Source: National Records of Scotland (2024) (25)

Figure 1.4 Difference in mortality rates for cancer and coronary heart disease (CHD) (age-sex standardised rate per 100,000) between the 20% most and least deprived areas of Scotland

Source: National Records of Scotland (2024) (25)

Research suggests that policy measures that are mandatory and population wide (such as product reformulation, fiscal measures and restrictions on products and marketing) are both more effective in achieving reductions in risk factors at population level, and more likely to reduce inequalities, than voluntary measures (such as health promotion campaigns) (26,27). The multifaceted tobacco control measures implemented in Scotland and the wider UK in the 2000s have yet to be mirrored for alcohol and unhealthy food. Indeed, Scotland’s post-devolution food reformulation and public education efforts have been primarily voluntary, with limited impact on increasing fruit and vegetable consumption to recommended levels (14). The underlying material, social and environmental factors associated with disadvantage have been identified as a significant barrier to the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce key risk factors (28).

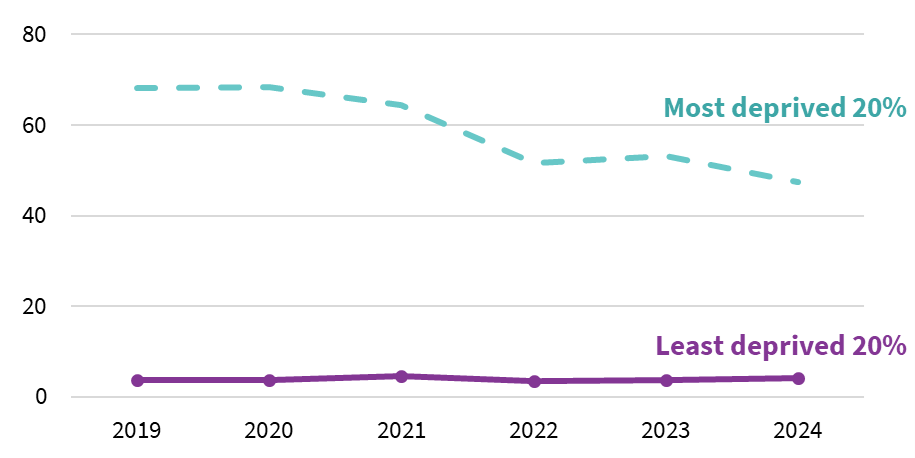

Figure 1.5 Drug-related mortality rate (age-sex standardised rate per 100,000)

Source: National Records of Scotland (2025) (29)

Figure 1.6 Alcohol specific mortality rate (age-sex standardised rate per 100,000)

Source: National Records of Scotland (2024) (29)

Poverty and household income

Household income plays a critical role in explaining health inequalities, and there are dramatic differences in health outcomes between wealthy and poor groups. Limited income makes it harder for people to adopt healthy behaviours and creates stress for households struggling to make ends meet. There are obvious negative outcomes from this: people may struggle to afford essentials like food or heating. Perhaps less obviously, the gap between those with low incomes and those with middle or higher incomes can also lead to social isolation – a factor that negatively impacts health (30). This can be because people cannot afford to participate in common societal activities, such as paid-for school trips or social events that involve paying for food or drink but can also be a result of people trying to avoid the stigma of poverty (31).

The latest data incorporates the financial year 2023-24 where the “cost of living” crisis was at its height. These data are presented as real-terms changes (all previous year’s figures are uprated to the latest year) so the uptick for most households is a real improvement in living standards. Factors which will have impacted on incomes in this year include pay rises (including the National Living Wage and the Minimum Wage) and additional targeted cost of living payments.

Median incomes, illustrated in Figure 2.1, rose in the three-year period[1] from 2021 to 2024 relative to the previous three-year period (2020-2023) across most population groups, with the exception of pensioners which may be at least partly explained by their greater reliance on fixed incomes and savings which tend not to adjust in line with inflation unlike earnings from employment.

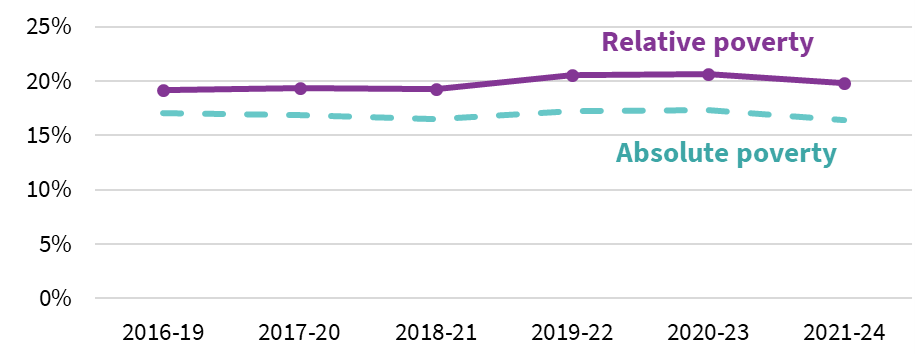

The most recent data, illustrated in Figure 2.2, show that poverty has reduced slightly, indicating a relative improvement in living standards for those at the bottom of the income distribution. This has particularly been the case for children (see page 17, Better news on child poverty).

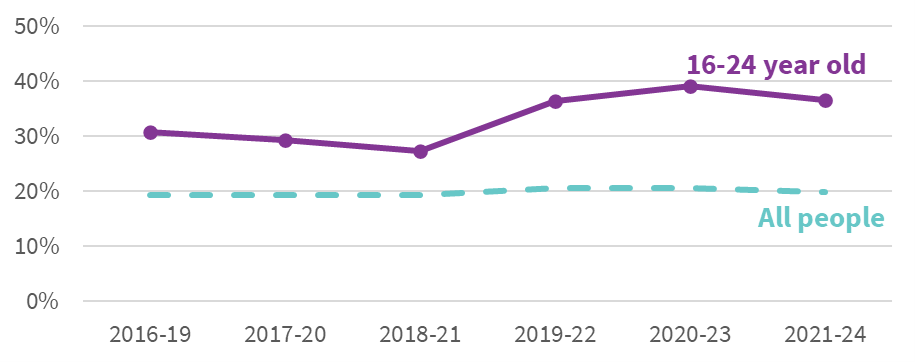

In last year’s report, we noted a particularly concerning trend for poverty among 16–24-year-olds, a period when many people are leaving home and transitioning to financial independence. Promisingly, there is now evidence that poverty is also starting to reduce for this age group although, as Figure 2.3 shows, rates remain far above the Scottish average.

Figure 2.1 Median weekly equivalised household incomes (in 2023-24 prices) before housing costs

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

Figure 2.2 Average yearly proportion of the Scottish population in relative and absolute poverty (after housing costs)

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

Figure 2.3 Average yearly proportion of non-dependent 16- 24-year-olds in relative poverty (after housing costs)

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

A 2025 review of children and young people’s experiences of poverty in Scotland provides additional evidence of the stress that experiencing poverty causes for this age group:

“It’s not healthy to have to regulate when you receive heat or not nor having to buy less/ worst quality food.”

16, Dundee (33)

“You can’t even sleep – worrying about not having food to eat. They [Council] need to provide food for young people.”

Unaccompanied, asylum-seeking young person (33)

Qualitative accounts also identify some place-based variations in young people’s experiences (e.g., between rural and urban areas):

“I get £67 per week. When I lived in Inverness this was enough to buy all my food. Now I live in [village] it is more difficult because they don’t have Lidl or Aldi, only a Co-op which is more expensive.”

Participant (33)

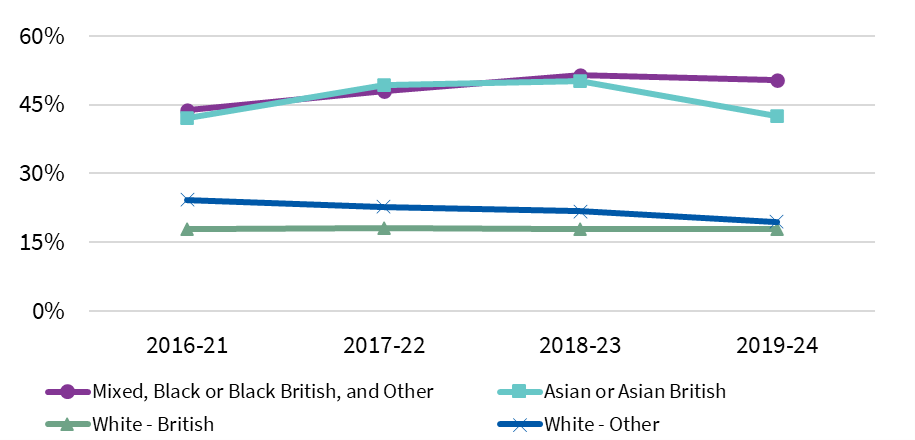

Analysis for households which contain one or more people from a minority ethnic group show that rates have also begun to improve for Asian/Asian British Households, although rates remain far above groups described as “White – Other” or “White – British”. The rate for “White – Other” has now moved closer in line with “White – British” whereas the combined rates for mixed ethnic groups, Black or Black British, and Other ethnicities have remained static (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Average yearly proportion of households including a member from an ethnic minority background in relative poverty (after housing costs)

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

Newly published research exploring the health and wellbeing experiences of minority ethnic unpaid carers in Scotland suggests that eligibility restrictions and challenges negotiating an unfamiliar social security system may both contribute to poverty in Scotland’s ethnic minority communities:

“I was alone, I didn’t have children. But then when you’re an immigrant you don’t have access, no recourse to public funds, what it means is you are always existing on eggshells… you’re just day to day. It’s a very, very stressful existence.”

Female, 45-64, Pakistani (34)

“The only reason I got the allowance was that Al-Masaar [a charity for minority ethnic carers in Forth Valley – now renamed Coalition of Carers and Rise Forth Valley] helped me complete the forms. If that wouldn’t have happened, then I still wouldn’t be getting that allowance and I’m not sure how I’d cope.”

Female, 45-64, African (34)

Better news on child poverty

One of the most significant policy responses to tackling poverty in recent years has been the Scottish Child Payment. As of April 2025, this provides an additional £27.15 per child, per week, to all eligible families (up from £26.50 in 2024-25). Data from March 2025 suggest approximately 326,000 children were benefiting from the payment, which equates to around a third of all children in Scotland (35).

Our report last year highlighted concerns that the increase in the Scottish Child Payment was not feeding through to income and poverty data as expected. We noted that this was likely to relate to issues with data collection.

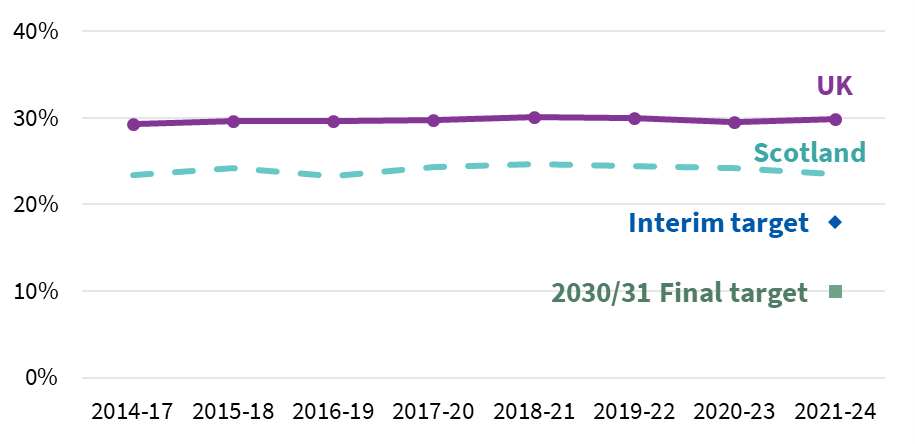

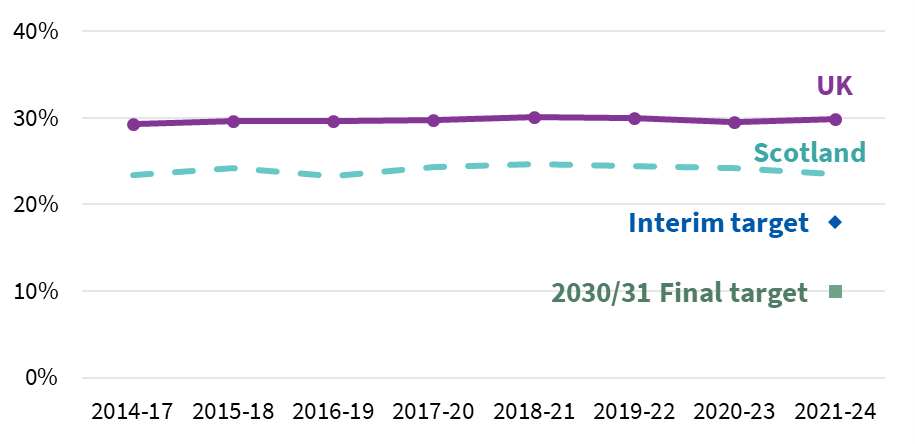

Since last year, there has been a welcome change in the methodology for capturing the Scottish Child Payment. As Figure 2.5 shows, data released in March 2025 (for the year 2023-24) demonstrate a small decline in child poverty and indications of a deviation from the UK trend. Whilst the change is small when looking at the three-year average, we would expect this trend to be consolidated as more years of data is gathered.

Figure 2.5 Average proportion of children in Scotland and the UK in relative poverty (after housing costs)

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

Note: Data collected for the financial year 2020/21 is not included due to issues with data quality in this year.

Following discussions with Scottish Government, colleagues from the Fraser of Allander Institute tested the new methodology to assess whether it did a better job of capturing children who were eligible for the payment. Ultimately, they concluded that adopting the new methodology sooner would not have changed the poverty rate in the 2022-23 data, but the new method does a much better job of capturing the number of people receiving SCP, giving us more confidence in figures going forward (36).

In our 2024 Inequality Landscape report we said that, even if the Scottish Child Payment was showing up in the data as expected, Scotland would still be some distance away from meeting its statutory child poverty targets (1). Unfortunately, the new data released in March 2025 confirmed that the 2023-24 interim child poverty target was not met.

SHERU analysis, published shortly after the new data release, also looked at child poverty for different social groups (37). This showed that child poverty was falling for lone parents, and children living in a household where at least one person was from a minority ethnic group but was increasing for families with three or more children (Figure 2.6) and had plateaued for households with at least one disabled person. And while child poverty fell in urban areas, it rose in rural areas. This shows that, although the Scottish Child Payment appears to be reducing child poverty overall, there are other countervailing factors that may be limiting its impact on some families.

Figure 2.6 Proportion of households in relative poverty by number of children in household

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

While the Scottish Child Payment at its current rate will not be a sufficient policy intervention to meet child poverty targets, the value of these payments to families has continued to be articulated by those who receive the payment. For example, a participant in the Changing Realities project shared the following account of the difference the payment was making with the First Minister in April 2025:

“Now, with the payment at £26.70 per week, it has allowed me and my son to afford social and educational activities we would otherwise miss. It has reduced financial pressure, supported my son’s health, and given us more breathing space to enjoy life. Kids need to thrive – not just survive. The Scottish Child Payment has been instrumental in our lives. It has enabled me to invest in healthier food, which supports my son’s learning and brings me peace of mind. […] As someone with lived experience of mental health challenges, the SCP has been vital in easing stress and improving our quality of life. This has had a direct, positive impact on my son… […] While I applaud the government’s commitment to tackling this through the SCP, more is needed.”

Isabella-rose F (38)

This extract reflects broader, lived experience accounts, with families generally reporting that the payment helps them to cover essential costs and access activities for their children, but remains insufficient to fully alleviate the anxiety associated with economic insecurity (39). A recent Scottish Government report, Learning from 25 Years of Prevention, includes the Scottish Child Payment as a case study of primary prevention, though acknowledges the evidence of impacts is still emerging (40). In September 2025, the Scottish Government published a report offering new insights into claimants’ accounts of the Scottish Child Payment’s impact, though further work is required to more robustly assess the effects on health outcomes (41).

The year ahead will bring some significant changes to how data on income and poverty is captured across the UK. DWP will be linking their administrative data on benefit income and potentially HMRC data on earnings. The current source of data, which we have relied on in this section, comes from the Households Below Average Income Survey, which significantly underreports income from benefits. This administrative data linking will ease this issue and, as such, we expect households accessing benefits to see increases in their income in the official data which means, holding all else equal, we should see a decline in poverty rates.

As yet, the extent to which devolved Scottish benefits will be included in this administrative data linkage is unknown. Without such inclusion (or some new methodological innovations, as has now happened for the Scottish Child Payment), incomes for people in Scotland who draw on Social Security Scotland administered disability and carer benefits will start to look markedly (and misleadingly) worse compared to people in England and Wales who draw on DWP administered benefits.

Beyond these data innovation related changes, there is likely to be little change in income and poverty with no new policies likely to positively impact poverty rates having been introduced in the UK or Scotland in 2024-25. The withdrawal of some cost-of-living payments that were paid during the financial year 2023-24 could show up as a reduction in incomes for some households.

While efforts to mitigate the impact of the two-child benefit limit in Scotland should show in future data, this will likely not be before 2026-27. Countering this, the impact of UK Government welfare reforms, for example the reduction in the health-related top ups to UC for new claimants, will also start to take effect in 2026-27.

Spotlight on debt

Debt is an important aspect of the money available for household spending which is not captured in most data on income and poverty. It can take on many forms but is generally considered to be money that individuals or households are legally obligated to repay in future. Debt may accrue for a wide range of reasons, often relating to household needs, and can accrue on a short-term or long-term basis.

Debt is not always harmful if repayments are manageable. Mortgages, for example, spread the cost of an asset and can raise living standards. Problems arise when debt becomes unaffordable (“over-indebtedness”), which is linked to poorer physical and mental health and is both a cause and a consequence of poverty (42).

Levels of debt are usually captured in surveys that look at household assets (in Scotland, the main data source is the Wealth and Assets Survey, which is conducted every two years, although along with other statistical publications in the UK at present, there are concerns over robustness of the latest data). Surveys typically rely on people’s willingness to declare debt. Stigma, especially around some debts, such as gambling, can lead to under-reporting (43).

The ongoing issues around the rising cost of living continue to exert significant financial pressure on households across Scotland and for some people this has compromised their ability to manage and service existing debts. Inequalities in available financial services and support mean that low-income households are often forced to take on high interest loans, further exacerbating income pressures (42).

“We’ve had no savings, since the beginning of COVID. Everything has gone up – our overdraft is maxed out most of the time. The safety net is being used. We can plan for things and save up but when a big-ticket item goes, the money isn’t there. When the cooker went – we applied for a loan, got knocked back. I had to ask my dad to put it on his credit card and pay him back. We didn’t have a choice – we needed to feed the kids. The same bank won’t give us a loan to repay at £20 a month, but they’ll happily take £17 a month in overdraft charges”.

Gordon (44)

Public debt (i.e., debt which is monies owed to public bodies e.g. local authorities such as rent arrears, council tax arrears, school meal debt or DWP repayment of Universal Credit advances) also continues to be a problem faced by low-income households in Scotland. Analysis collated on the Universal Credit in Scotland has found that, in February 2025 alone, £17.4 million is being deducted from Universal Credit payments across Scotland. When annualised, this amounts to nearly £210 million in deductions each year (45).

In 2025, Citizens Advice Scotland noted that council tax debt was the single most common debt type people had been seeking advice about (46). An earlier Citizens Advice Scotland report expressed concern that councils have been sharply increasing debt enforcement (in contrast to other types of creditors), using tools such as bank account freezes, wage and benefit deductions, and “Exceptional Attachments” that let officers enter homes to seize goods (47).

Research in Scotland has found that household debt is disproportionally impacting families with lone parents with a disabled child or children in the house (45). Qualitative research on the experience of households affected by public debt in Scotland found that this was exacerbating household income inadequacy, leaving some people taking on other forms of consumer debt to cope:

“So I was paying all this stuff out and I literally was struggling. It was making my mental health worse. Obviously, I had a lot to deal with already and it was horrible. So that was like – I ended up getting in debt with my housing benefit as well. So then I got into rent arrears because I didn’t pay that into my rent because I physically, I had two children I physically couldn’t do it”

Laura (48)

Policymakers have acknowledged this issue in Scotland, and we have seen, for example, investment to support local authorities in writing off school meal debt to help mitigate the cost-of-living crisis (49). In the coming year, SHERU will work with others to better understand the role that household debt is playing in Scotland as a socio-economic determinant of health inequalities and the potential for policy measures to help reduce these impacts

[1] As is standard practice, we use three-year averages to illustrate trends in incomes and poverty. However, because of data issues in 2020-21, any period that would normally include that year has instead been calculated using a two-year average.

Education & early years

The relationship between education and health is complex. Education is shaped by the same socio-economic conditions that influence health and is sometimes used as a proxy for childhood socio-economic position (50). Many health outcomes are worse among people with less education, but evidence that more education directly improves adult health is mixed. There is evidence that educational attainment mediates links between childhood socio-economic adversity and health-harming behaviours in adulthood (50) and that bullying in childhood is a risk factor for a wide range of poor social, health, and economic outcomes in adulthood (51). We also know that experiences at school can provide the foundation for secure living standards in adulthood (52), through qualifications achieved, wider skills and capacities, and via social networks that are enabled (53).

Inequalities begin before birth (54). The importance of the early years for health across the life course is well established, with broad consensus on the need for early support and interventions to reduce health inequalities (55,56). Scottish policy aims to reduce their impact by supporting families – financially and through early-years and school settings. Despite sustained efforts to reduce the attainment gap, such as implementing policy initiatives including Getting it Right for Every Child (57) and The Promise (58), indicators of childhood inequality remain stubbornly high.

Lower socio-economic circumstances affect many aspects of early family life. Across high-income countries, people living in deprived circumstances experience worse pregnancy outcomes (59). In Scotland, childhood experiences are shaped by limited household income, which reduces the potential to participate in social activities; family stress, which arises from difficulties meeting essential costs including food, housing, energy; and the condition and quality of accommodation and key services (notably education). These socio-economic and contextual factors interact to influence child development, wellbeing and families’ long-term opportunities.

Play – at home and in the community – is critical in early childhood. Its importance is recognised in Article 31 (Leisure, play and culture) of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990) (60). Play underpins children’s language, physical and cognitive development and other contributors to health and wellbeing (61). Yet many low-income families in Scotland report barriers to high-quality play, including prohibitive costs and a lack of suitable, accessible spaces (62).

“Why do you have to be minted to take your baby swimming?”

Parent in Scotland (63)

“There is nowhere in my street that is safe to meet up with friends and play, my friends live 10/15 min walk from me, my mum won’t let me out by myself because the traffic is busy and it’s boring by myself if my friends aren’t with me.”

Boy, 9, Glasgow (61)

Early years have been a core policy focus in Scotland, with investment in flagship measures such as funded childcare for eligible two-year-olds and 1,140 hours of free childcare for three- and four-year-olds through funded early education and childcare (ELC) providers (64). This reflects policy recognition that “a fully functioning childcare sector is a pivotal part of Scotland’s national economic infrastructure” (65). Despite this progress, gaps remain in the cost and availability of provision. A Joseph Rowntree Foundation poll of parents with children under age five found that nine in 10 parents wanted more funded early years childcare. The research also identified groups facing additional barriers, including families in part-time, insecure employment and households with irregular or shift work (66).

Wider research supports these findings. A longitudinal study tracking workers in Scotland’s hospitality sector – typically characterised by low pay and insecure hours – reported similar challenges, with parents struggling to access childcare that fits their work patterns.

“Because me and my husband, we both work extra hours every week to be afford – like to be able to afford to live kind of thing. Without the extra hours, we wouldn’t be able to survive”

Carla, remote rural area (67)

Free childcare is an important policy, but it must be integrated with other services to work well for families.

“I began a college course… I had to leave home at 7am to walk across town with my child to childminder, as no buses to that area, then walk back across town to catch bus then run, on foot, to college for a 9am start…. I had a breakdown as both myself and my child were exhausted from this due to heavy traffic and late picking up child and being charged late fees.”

Single parent, one child, rural area (68)

The early years are a critical period for physical, cognitive and socio-emotional development, with long-term effects on health and life chances. Targeted support at this stage can reduce inequalities and build a stronger foundation for future learning and there is a clear need to focus on aligning provision to the needs of low-income families. As such, educational attainment is closely linked to early experiences and to the availability of sustained support throughout a child’s learning journey.

Improving children’s lives and attainment depends on cross-government policy, including efforts to reduce child poverty and improve housing, both of which have been the subject of high-level Scottish Government strategies. These actions should improve outcomes, but this is dependent on effective implementation. Monitoring and evaluation are needed to track their impact on both immediate outcomes and more distal health experiences.

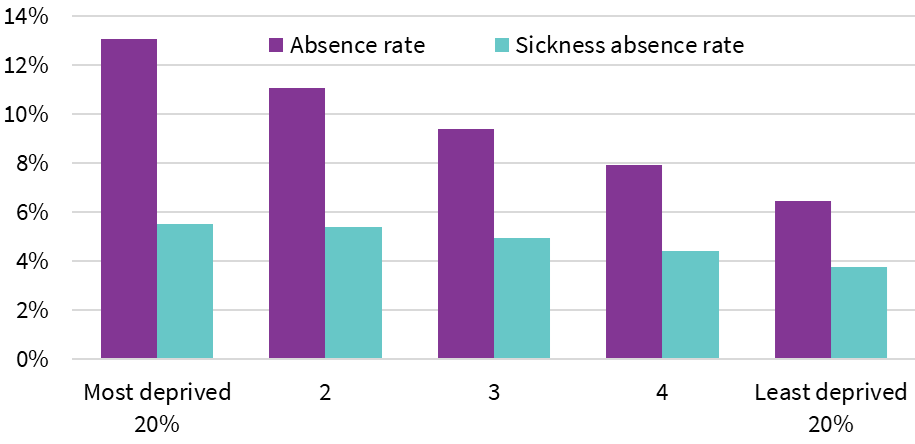

The gap in developmental concerns at 27-30 months narrowed slightly over the last year but remains wide at 15.6 percentage points – close to the highest level since 2014/15. In the most deprived areas, levels are similar to those seen nearly a decade ago, suggesting persistent early development challenges with little long-term improvement (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Proportion of children who have developmental concerns at 27-30 months

Source: Public Health Scotland (2025) (69)

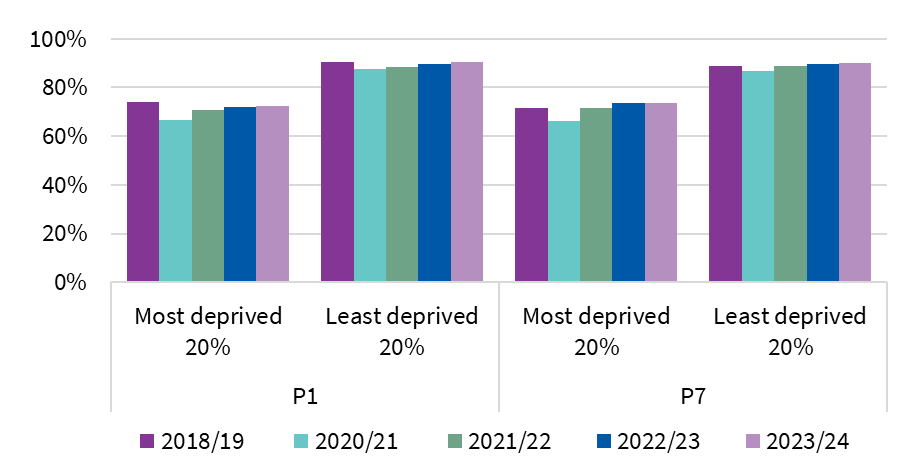

The latest data on inequalities in educational outcomes at primary school level shows little change on last year, meaning the gaps in meeting grade-level expectations between the most and least deprived pupils remain similar to those seen before the pandemic (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Proportion of P1 and P7 students meeting grade level expectations in reading

Source: Scottish Government (2024) (70)

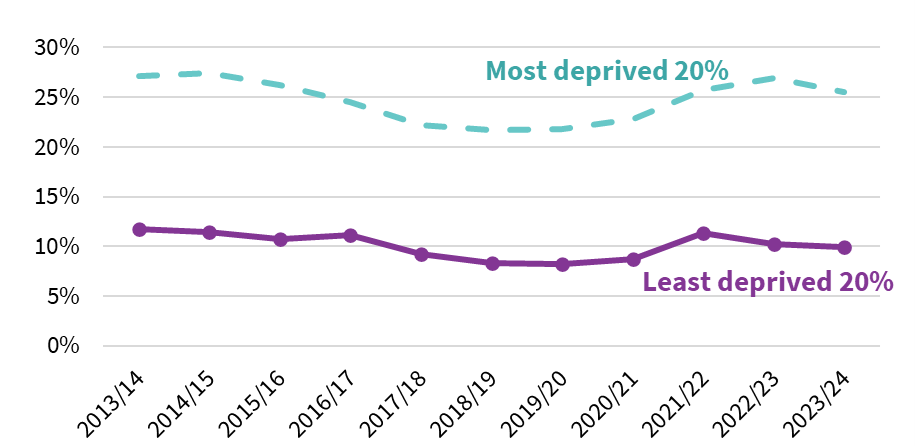

Rates of attendance at school have been falling in recent years, across all pupils. Moreover, pupils from the most deprived areas continue to experience lower attendance rates compared to those from the least deprived areas. Sickness absence rates are also higher in more deprived areas (which may be a manifestation of early health inequalities). Rates have changed very little in the latest data. This persistent gap in attendance highlights ongoing challenges facing disadvantaged students and a risk of disengagement, which can lead to poorer educational outcomes and exacerbate existing inequalities (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Proportion of half days of possible attendance recorded as absent in school by students’ deprivation quintile, 2023-24

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (71)

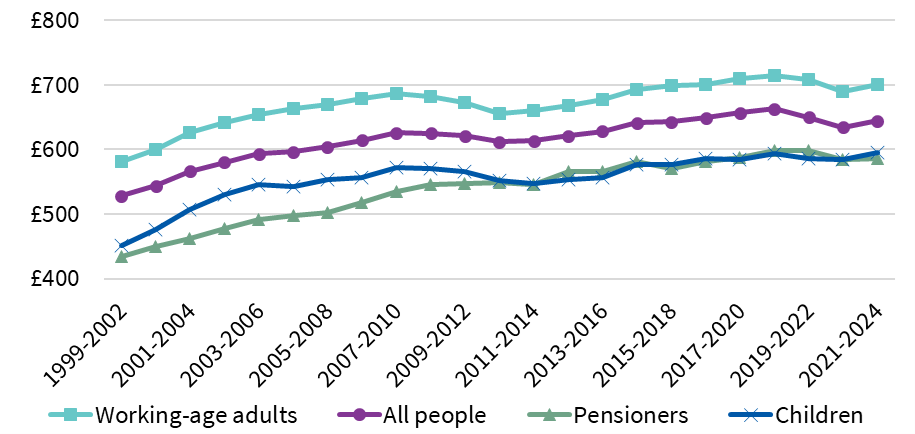

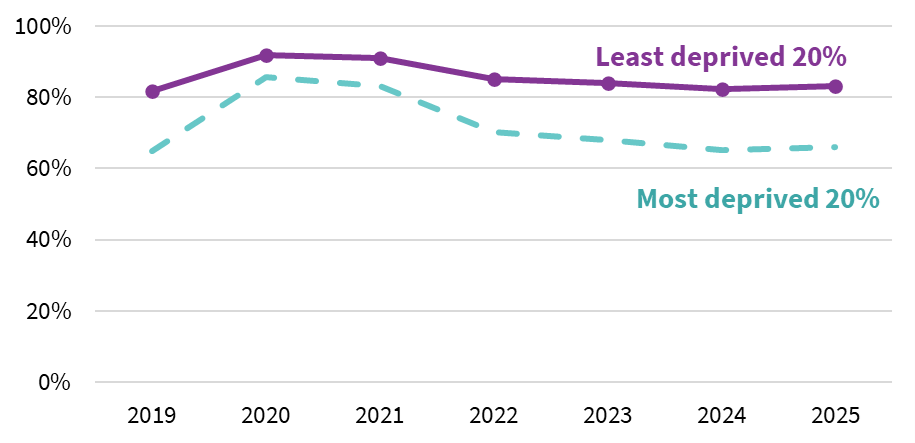

In 2025, Scotland recorded positive progress, with the attainment gap narrowing between the most and least deprived 20% of communities, driven by improved pass rates (grades A-C) across National 5, Higher (Figure 3.4) and Advanced Higher qualification levels. Nonetheless, the rate of improvement remains modest, and the disparity between advantaged and disadvantaged students endures, with the persistent link between poverty and educational outcomes continuing to limit progress.

The Scottish Government’s wider struggle to meet its interim child poverty reduction targets has further hindered efforts, leaving its 2016 commitment to “substantially eliminate” the attainment gap by 2026 increasingly out of reach.

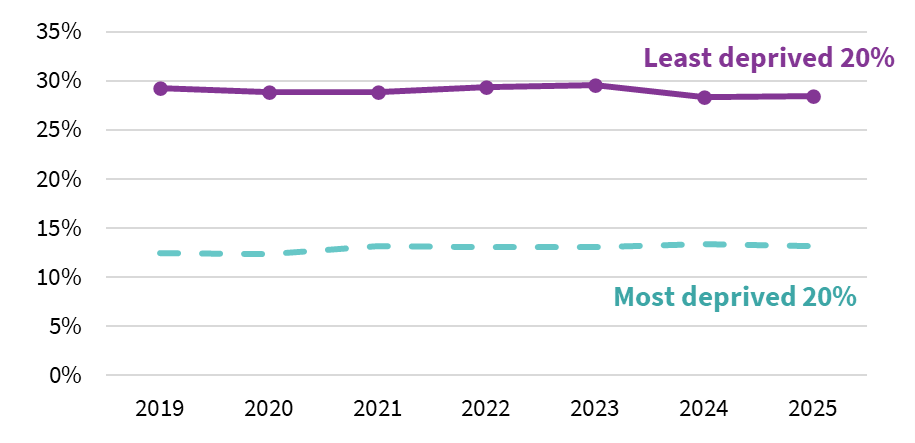

Meanwhile, the gap in higher education participation among 16-19-year-olds remained largely persistent throughout the pandemic, with a modest narrowing in 2024. In 2025, participation rates for the 20% least and most deprived remained largely unchanged, despite a slight widening of the gap compared to the previous year (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.4 Proportion of candidates attaining grade A-C at Higher

Source: Scottish Qualifications Authority (2025) (72)

Figure 3.5. Proportion of people aged 16-19 participating in higher education

Source: Skills Development Scotland (2025) (73)

A new mixed methods study of Scottish young people from areas of high deprivation who had accessed higher education, features qualitative accounts of their educational journeys. It identifies unequal access to advanced subjects as a key barrier to progress, particularly Advanced Highers, and highlights how this can limit access to some competitive degrees, such as medicine and STEM subjects (74). Many students also felt their educational opportunities had been limited by their schools’ comparative lack of funding and resources, which led to a high staff turnover and limited sense that there were people who cared about their outcomes:

“it’s like vastly different … it’s like actual like teachers and stuff… my school in my last year I did English Higher English and… we had three teachers a week… it’s like the actual lack of like staff and even when you do have staff there’s a lot of staff that are like, ‘aw we’ve given you the resources, if you fail, you fail – I don’t care, go away and learn it’”

Saoirse (74)

Employment

The links between the work that people do and their health are multifaceted. There is a lot of concern about people who are not engaged in the labour market (referred to as economic inactivity), but we also know that quality of work, which encompasses job security, working conditions, and the level of stress associated with a job, plays a critical role in people’s physical and mental health. Both having a job and the quality of that job are linked to earnings, which is a significant component of household income.

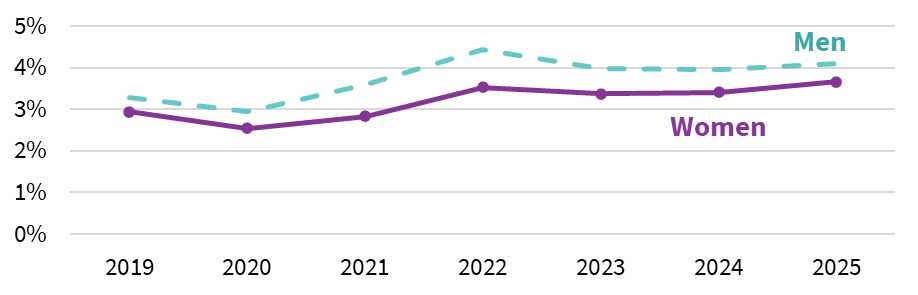

Unfortunately, it is becoming increasingly difficult to monitor what is happening with the labour market in Scotland, which means that it is difficult to understand recent trends and the resulting intersection between health and employment. Most data on the labour market in the UK comes from the quarterly Labour Force Survey and the Annual Population Survey, both published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The quality of data produced from these sources has come under a lot of scrutiny in the last couple of years due to concerns around falling sample sizes and increasing volatility.

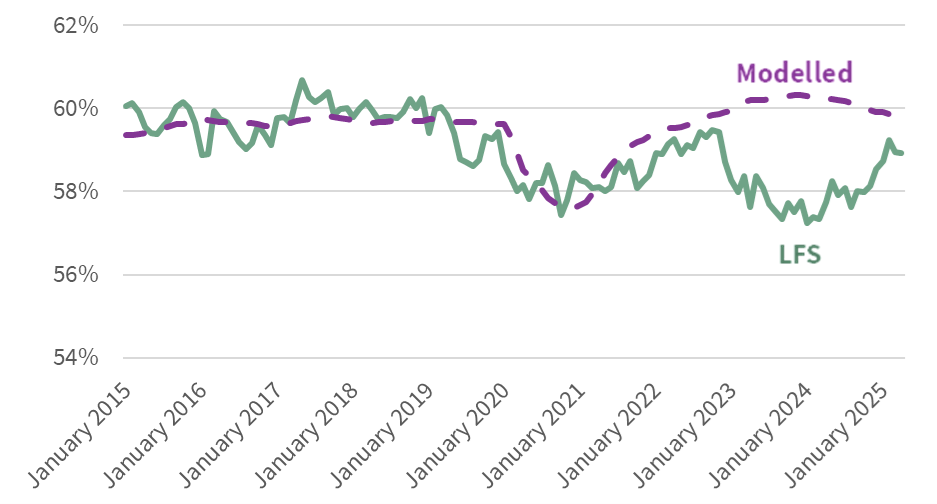

The Scottish Government and the ONS have assessed the reliability of labour market statistics and using their quality thresholds and have found that headline statistics of employment, unemployment and inactivity, are deemed “robust.” However, analysis by the Resolution Foundation for the UK, replicated by SHERU for Scotland, used administrative data from HMRC’s PAYE data, and found evidence to suggest that employment has been stronger than the Labour Force Survey suggests. If this is true, then it follows that the number not in employment (i.e., those categorised as unemployed or economically inactive) may not have risen as much as the LFS suggests (Figure 4.1) (75).

Figure 4.1 Modelled employment rates, 16+

Source: SHERU (75)

For more specific categories with small numbers of responses, there is less confidence from official statisticians in the quality of indicators. For example, the Scottish Government reported lowered confidence in the statistical quality of five out of nine possible survey responses under “reasons for inactivity,” and “whether want to work” in 2023 compared to 2019 (76). Given these issues, we have chosen not to show updated statistics for inactivity by reason in this year’s report. However, the Scottish Government, along with other organisations, continue to use this data widely, perhaps because long-term sickness and student data are rated as “high confidence” in both 2019 and 2023, even though confidence in other reasons for inactivity have declined over time. The current statistics show a rising economic inactivity rate and a large increase shown in the number of people inactive due to long term ill health (77).

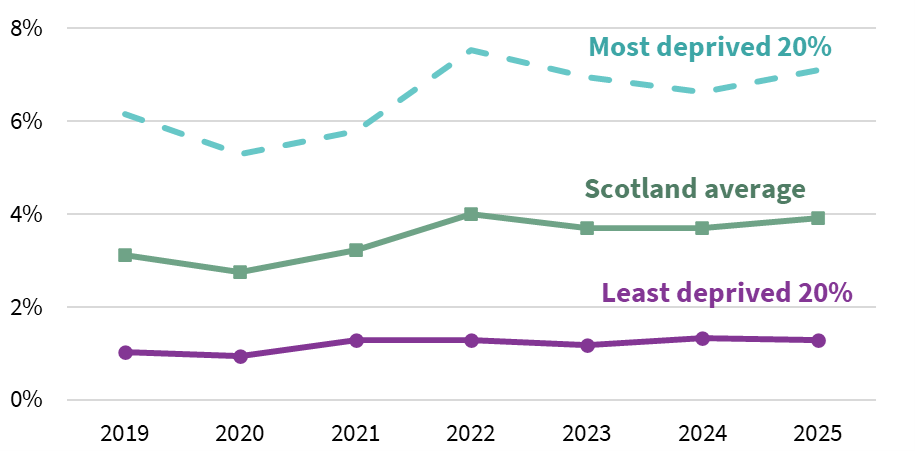

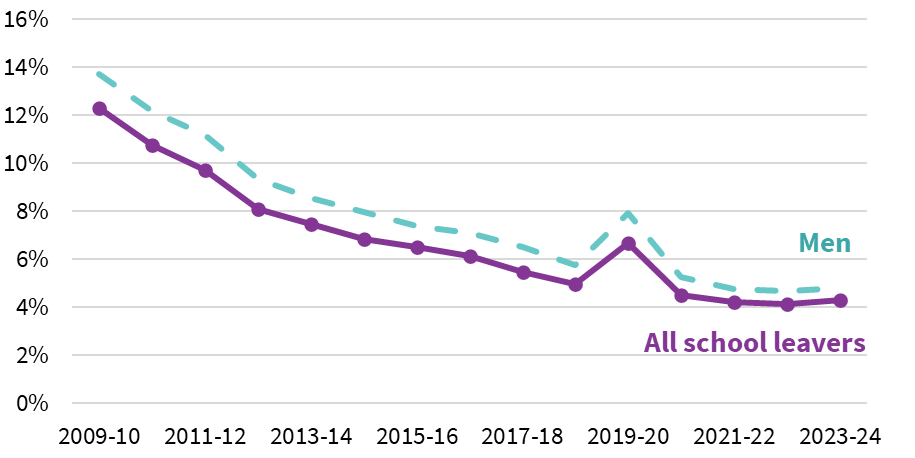

Alternative official statistics on inactivity for those aged 16 to 19 exist in Scotland through the Annual Participation Measure. This measure utilises data from Skills Development Scotland’s customer support system. According to these data, the share of 16–19-year-olds confirmed as not participating in employment, education or training rose across Scotland over the past year, reaching 7.1% in the most deprived areas, while remaining stable at 1.3% in the least deprived (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Proportions of those aged between 16 and 19 who are not participating in education, employment or training

Source: Skills Development Scotland (2025) (73)

Another possible source for insights on the relationship between health and work in Scotland is administrative data from the benefit system. Here there has been an increase in the number of people claiming the health component of Universal Credit (UC) and/or disability benefits. A rise in the number of people on these benefits is not necessarily correlated with an increase in people not working, as people on these benefits may be in work or out of work.

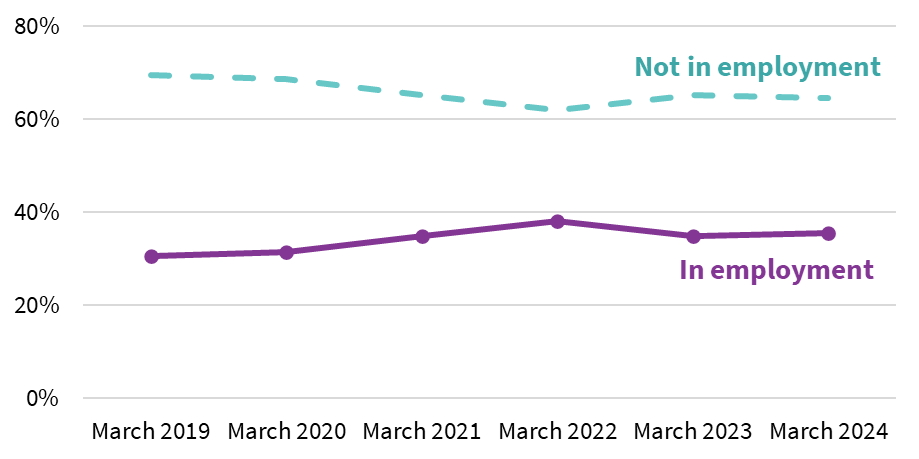

However, we can look at data on the proportion of people on UC who are in work in Scotland. If the increase in people claiming the health component of UC was also correlated with more people being unable to work due to illness or disability, then we would expect to see an increase in the proportion of people on UC who are not in employment.

Figure 4.3 shows, whilst there is evidence of a slight recent rise in the proportion of people accessing on UC who are out of work, the rise is small, and the proportion remains below pre-pandemic levels. We aren’t seeing evidence of step change in the number of people out of work and on UC since the pandemic, but there are other factors that might be affecting this data. For instance, different cohorts across the long-running managed transfer of people from “legacy” benefits such as Employment and Support Allowance may have particular employment characteristics that could skew the data one way or another. Unfortunately, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) does not provide a breakdown of employment status for those newly claiming the Health Element of UC.

Figure 4.3 Proportion of those on Universal Credit in Scotland by work status

Source: SHERU analysis of DWP (2025) (78)

Social Security Scotland do not publish data on work status for people on devolved disability benefits, but analysis presented by the DWP for PIP for England and Wales in their Get Britain Working green paper showed that, since the pandemic, the proportion of PIP claimants who are employed has started to increase, from 14% in March 2021 to 17% in March 2024 (79). Again, this does not corroborate a trend of rising inactivity due to ill health.

Where does this leave us? Whilst there is evidence from the benefit system and from elsewhere that supports the fact that there are more people seeking additional medical and/or financial help due to ill health (80), there is clearly reasonable doubt that this is leading to the large increase in economic inactivity described by the Labour Force Survey.

We note that a range of high-profile economists have raised concerns on labour market data being used for policy making, including Richard Hughes, chair of the OBR, and the Bank of England Governor, Andrew Bailey. And yet, we see both Scottish Government and UK Government ministers citing Labour Force Survey data uncritically and using this to push ahead with responsive action (81,82). At the UK level, this is part of the discourse justifying controversial welfare reforms, whilst in Scotland, less controversially, these data have been cited in relation to plans to push ahead with a health and work action plan.

“The LFS is essentially useless.”

Xiaowei Xu, senior research economist at the IFS (83)

This is a difficult position for policy makers to be in. If rising economic inactivity related to ill health and disability is real, as the Labour Force Survey suggests, the long-term consequences for both the population and the economy could be severe. And regardless of recent trends, there is a long-standing gap between inactivity rates in Scotland and the rest of the UK due to ill health. Nevertheless, we would like to see appropriate caveats and caution used by the Scottish Government and other public bodies when putting forward labour market evidence to justify policy changes or strategic intent, and more exploration of alternative data sources.

Given the issues with the quantitative data, it is especially important to consider insights from available qualitative research. We have yet to see studies that take a longitudinal approach to understanding employment experiences since the pandemic, but Public Health Scotland published a report in 2025 drawing on participatory research exploring mental health in and out of work (84). The accounts within this report suggest that a lack of flexibility and mental health support within work settings contribute to people feeling unable to stay in work, while a “one size fits all” approach to employment services limits opportunities to return to work for people with ongoing mental health challenges.

“…you must go through occupational health before you start and they knew I have mental health issues but there wasn’t really an offer of ‘Oh, there is such and such a service we provide, and if you feel you need to, you can attend there’. There wasn’t anything like that. Basically, the senior staff were just interested in why I couldn’t do night shift. I was hounded about it.”

Sarah (84)

“[…] it doesn’t work for people’s mental health, a one size fits all rule for people who are looking for work doesn’t work. Because you have got people who are out of work who are way over qualified for jobs that they are forced to apply for just so that the job centre can tick boxes to say that they are applying for jobs and they are wasting time and they can’t actually apply for jobs, like worthwhile jobs, where they would actually be boosting their mental health if they were filling out the applications and they are just sinking down this slippery slope.”

Fiona (84)

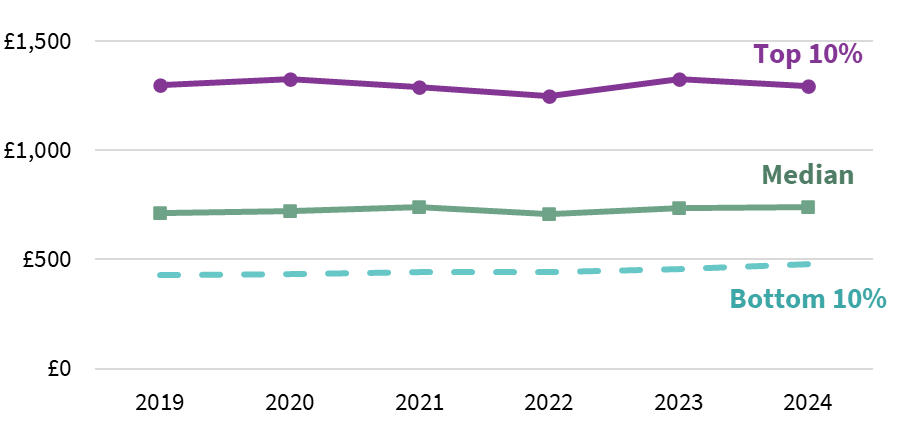

One labour market indicator that we can look at with more confidence is earnings. Data on earnings comes from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), which is based on a 1% sample of PAYE data and fortunately does not suffer from the same issues that the Labour Force Survey is facing. Here, there has been a marginal narrowing of the gap in the 2024 statistics, driven both by real-terms increases for the bottom 10% (likely partly driven by Minimum Wage and National Living Wage increases) and the median, and real-terms decreases for the top 10%, but the gap remains stubbornly wide (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Average weekly full-time employment earnings (in 2024 £)

Source: SHERU analysis of the Office for National Statistics (2024) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (85)

Housing and homelessness

Housing quality, access, and affordability all shape people’s physical and mental health (86). Housing affordability also affects disposable income, limiting the ability to spend on other necessities. Additionally, insecure housing tenure can be challenging for families seeking stability and, in extreme cases, can lead to homelessness, which is closely related to a wide range of poor health outcomes (87).

Scotland has ambitious aims on new housing, but these are increasingly undermined by the existence of the housing emergency, which is marked by rising homelessness, unaffordable rents, and a slowdown in new builds. This is placing huge pressure on national and local policy responses.

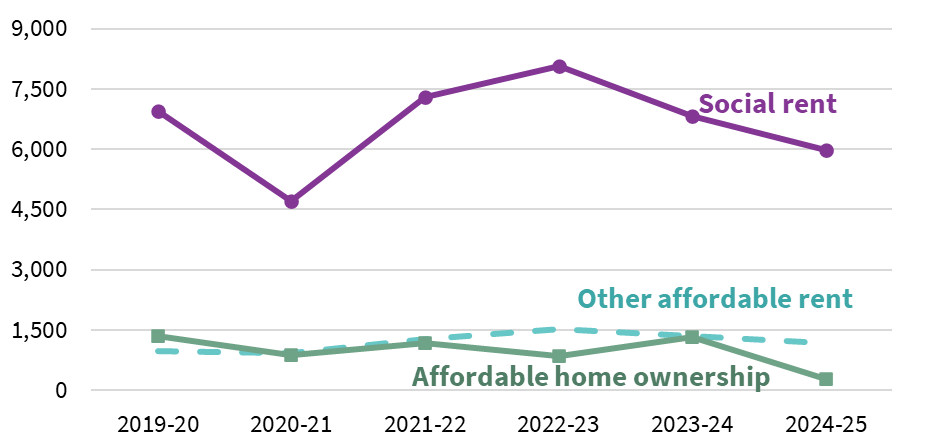

As Figure 5.1 depicts, the latest data on the number of new affordable homes built in Scotland shows a declining trend, particularly for homes built for social rent between 2022-23 and 2024-25. This comes after Scottish Government cuts to the affordable housing budget in 2022-23 and 2023-24. A restoration of funding levels in 2025-26 may help reverse this trend in future, but budget allocation remains below 2022-23 in real terms.

Figure 5.1 Number of new affordable houses built in Scotland

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (88)

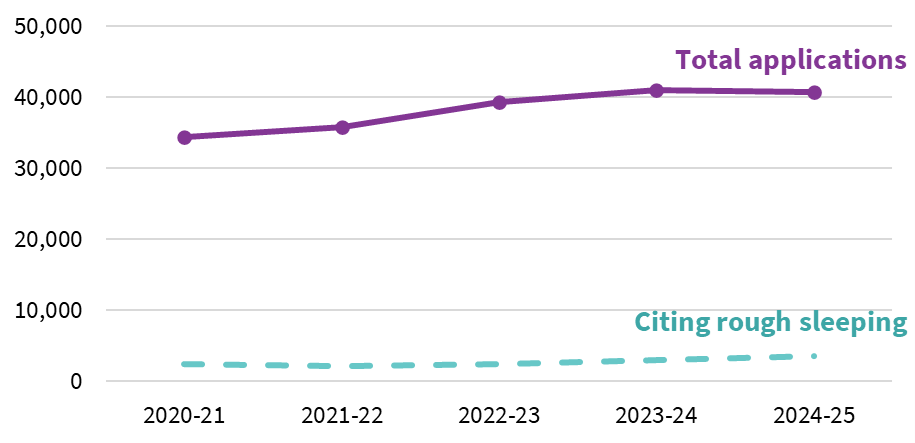

The Affordable Housing Supply Programme is part of a suite of measures intended to help ease homelessness levels. As Figure 5.2 shows, homelessness levels have risen in recent years, with a small decrease in application numbers in the most recent data. These figures only capture homelessness that is reported – a 2025 Scottish Government report examines the additional challenge of “hidden homelessness,” in which people do not declare themselves homeless but are living in unsuitable, temporary situations (such as sofa-surfing with friends or sleeping in their car) or in an abusive situation (89).

Figure 5.2 Number of homelessness applications and applications citing rough sleeping in the previous 3 months

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (90)

Despite a slight decrease in homelessness applications in the most recent year, the overall rise in homelessness has led to an unprecedented number of families in Scotland living in temporary accommodation. A 2025 report by Shelter Scotland documents families’ experiences of temporary accommodation, highlighting multiple issues, including cramped conditions, broken (or absent) heating systems, limited facilities (for example, for laundry), infestations, and concerns about neighbourhood safety:

“It’s so small, the rooms are literally just like that basically. I can’t even put anything other than a bed.”

13-year-old participant (91)

“In the winter it is very, very cold, very cold. And always this [health] is affected, I take him into hospital. I tried to open, because all the heaters don’t work, I just have, like, a heater, I buy it from Home Bargains. […] This is very expensive and the house is very cold, in winter.”

Mother of children aged 13 and 17 (91)

“Nowhere to wash our clothes”

Mother of children aged 10 and 5 (91)

“Within the first three months, there was a moth infestation. The carpet had a hole in it had been eaten, but a cupboard had just been placed on top. And I had been like, what? Where are all these moths coming from? Till I moved everything. […] I had rats […] My son […] ended up back in hospital with an infection that comes from animals. And he had been in hospital for two weeks ill. It did hit his chest again, yeah, to get help, to get rid of the rats, was almost near impossible.”

Mother of 4-year-old child (91)

“I had thumping music on at all hours, and to go to school after that, it’s just like so annoying. And also, you don’t really feel safe because you can’t exactly go and ask him to turn the music down or something, because he’s got lots of mental issues. And also the person next us in the flat, I don’t know, just doesn’t feel very safe. We were on the outskirts of the town we were in, but it wasn’t a safe town.”

15-year-old participant (91)

The consequences of this, as described by participants, include direct mental and physical health problems, social isolation (caused by regular moves and having accommodation that is too small to invite people into), and difficulties with accessing key public services (such as GPs or schools).

Another study released in 2025 noted variations in council support, highlighting that the quality of supported accommodation between, and within, councils seemed variable (33). In the year 2023-24 there were 7,400 households placed in temporary accommodation which was deemed by law to be “unsuitable.” These breaches of this law, the Unsuitable Accommodation Order, has increased over time, rising from around 6% of all households in temporary accommodation in 2022 to 12% in 2024 (92).

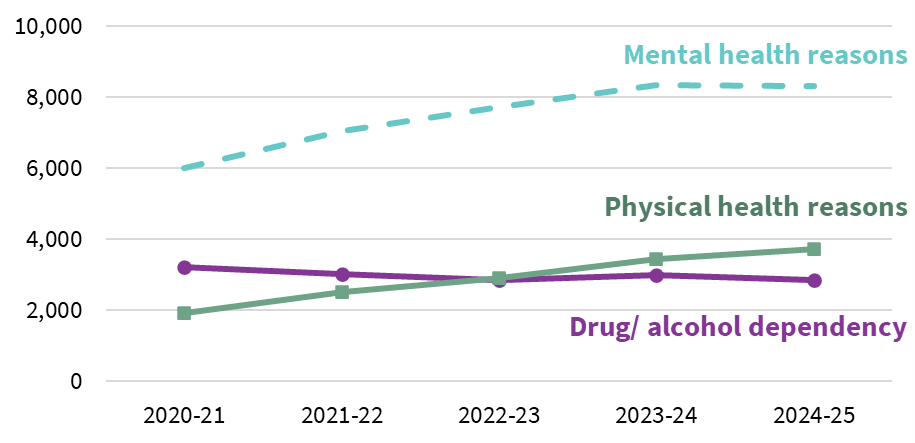

Mental health continues to be the most common reason for failing to maintain accommodation prior to a homelessness application. There has also been a notable rise in people citing physical health conditions as a factor, which has overtaken those citing drug and alcohol dependency (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Number of homeless applications citing mental health, physical health, or a drug or alcohol dependency

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (90)

A 2025 Scottish Government report exploring housing insecurity and hidden homelessness underlined the role that mental ill health can play in people’s pathways to becoming homeless:

“I was in a house with three kids with additional needs all in the one room. It was difficult. That wee boy was quite suicidal at the time as well, [he would] climb out windows and jump over bannisters and bring me knives [out the] drawers. It was difficult because he wasn’t getting his own space to regulate. So, we’re all very on top of one another and [it was] very frustrating.”

Participant (89)

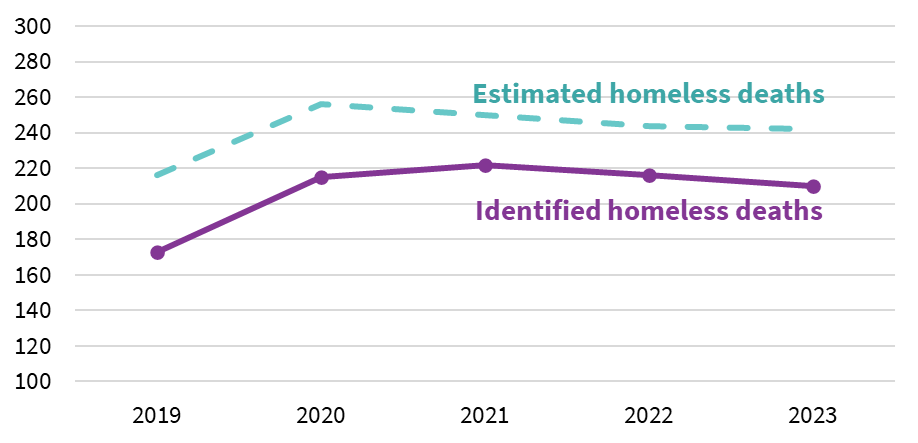

On a more positive note, the number of estimated and identified deaths amongst people experiencing homelessness continued to reduce slightly in the latest data for 2023. These statistics include people experiencing rough sleeping as well as in temporary accommodation (Figure 5.4).

For people who are not homeless, the quality of homes that people on low incomes live in remains an issue of concern, with damp and mould in particular presenting health hazards. Data on housing quality was disrupted during the pandemic but, with two subsequent waves of data from the Scottish Housing Conditions Survey which are comparable to pre-pandemic data, we can once again monitor changes over time.

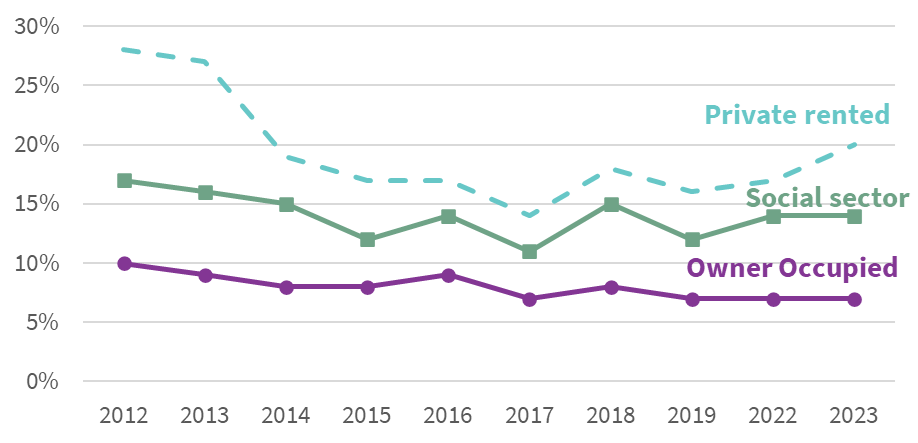

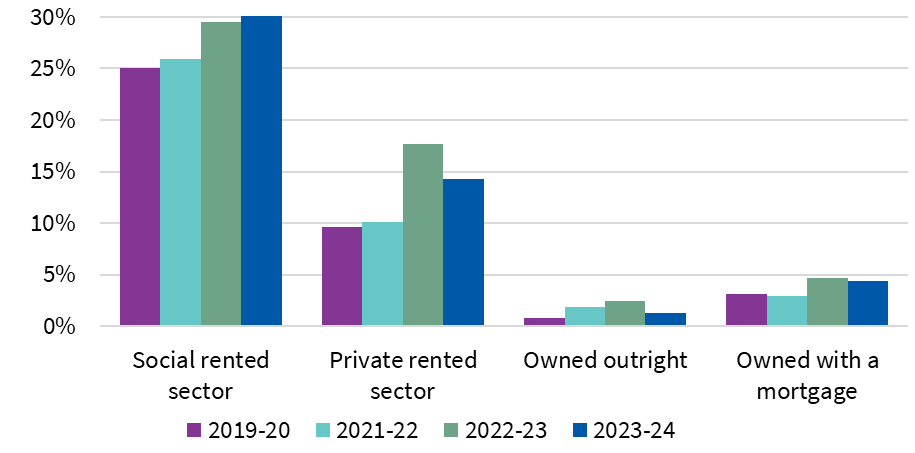

In the private and social rented sector, there has been deterioration in housing conditions, with an increase in reports of damp and condensation (Figure 5.5). The same survey reports an increase in mould within the private rented sector over the same time period.

Figure 5.4 Number of estimated and identified deaths among people experiencing homelessness

Source: National Records of Scotland (2024) (93)

Figure 5.5 Proportion of housing stock with damp or condensation by tenure

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (94)

Note: Data from the years 2020 and 2021 are not available due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As well as directly impacting people’s health, qualitative reports highlight how stressful living with damp and mould can be and note the material consequences of having to replace items that become mouldy:

“I moved from a flat to a house and the standard of living just went up extremely because, in the flat there was mould and damp on the walls. It was terrible living conditions. Anything you bought, like materials, after a while the damp would just sit into it and you’d have to get rid of it, because it was unbearable.”

Participant, age 17(33)

Being able to heat a home sufficiently is a further safeguard against poor quality homes. Rates of fuel poverty (based on the proportion of a person’s income required to heat a home and the residual income after fuel costs are deducted) continued to rise in the latest data, at 34% in 2023 compared to 25% in 2019.

An update on the impact of the rent cap

The Scottish Parliament is progressing a Housing Bill that includes Awaab’s Law, named after Awaab Ishak, who died in 2020 in England from mould exposure. The measure would set time limits for social landlords to investigate disrepair and start repairs. Similar duties are not currently planned for the private rented sector, even though these problems are often more prevalent there.

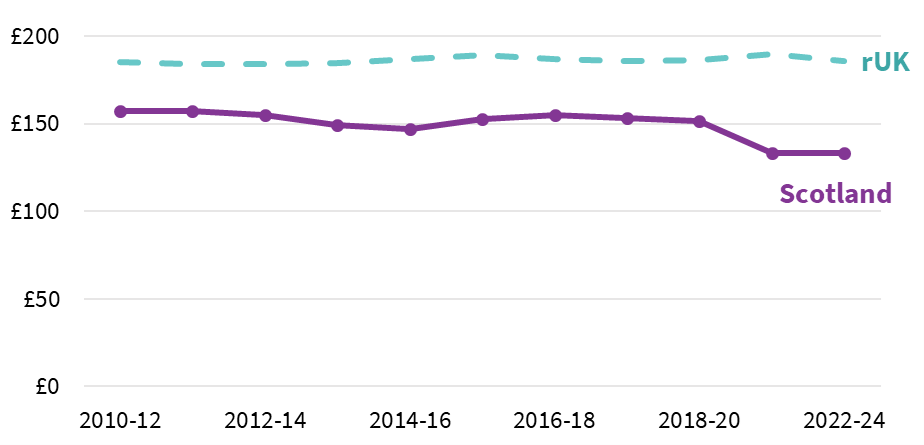

The Bill also proposes rent controls, allowing the Scottish Government to designate rent control areas based on evidence from local authorities. In our September 2024 Inequality Landscape report, we considered whether the rent cap, in place from October 2022 to end March 2024, might be driving relatively lower housing costs in Scotland. Preliminary data at that time (up to the end of 2023) showed private sector rents declining in Scotland, whilst remaining fairly flat in the rest of the UK.

Now we have data up till the end of 2024, and we do not see a continuation in the divergence between Scotland and the rest of the UK, which we may expect if the rent cap was having a significant impact on rents in Scotland. This suggest that the rent cap, which continued through to the end of 2024, may not have been the main driver of the previous reduction. As we noted in our 2024 Inequality Landscape Report, Scotland does not have good enough data on rents to analyse the impact of the rent cap more rigorously.

Figure 5.6 Weekly housing costs in the private rented sector

Source: SHERU analysis of DWP (2025) Households Below Average Income (HBAI) (95)

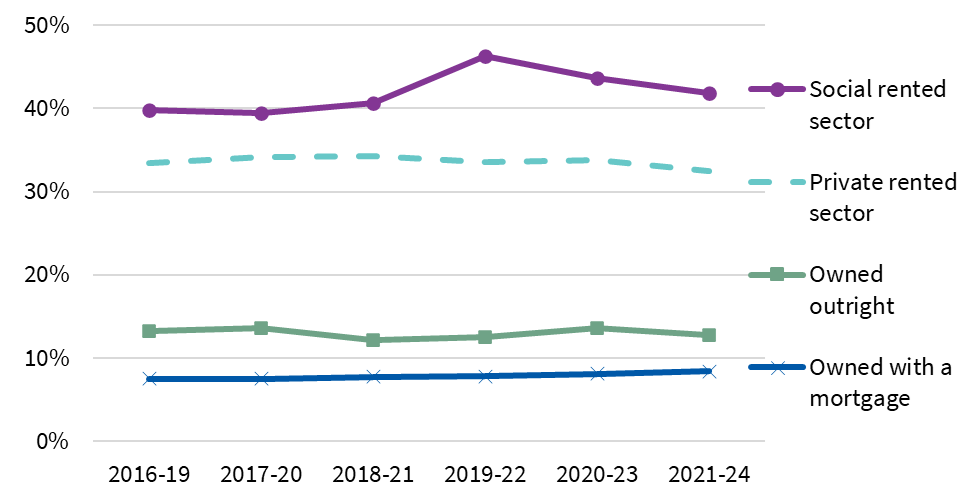

The main inequalities in terms of housing in Scotland remain between different tenures; those who rent tend to be poorer and, as seen above, are more likely to be living in poorer quality homes. Poverty rates within the social rented and private rented sectors are trending downwards but remain much higher than for owner occupiers (Figure 5.7).

Rates of food insecurity for people in the private rented sector have come down from their peak last year, while in the social rented sector they remain at about the same rate as last year. Levels of food insecurity among owner occupiers are much lower than in the two rental sectors (Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.7 Proportion of population in relative poverty by tenure

Source: Scottish Government (2025) (32)

Figure 5.8 Proportion of people that are food insecure by tenure

Source: SHERU analysis of DWP (2025) Households Below Average Income (HBAI) (95)

The Scottish Government’s ambitious Housing to 2040 strategy sets out a long-term vision for ensuring that everyone in Scotland has access to a safe, good-quality, affordable home that meets their needs and supports wellbeing. There are multiple references to addressing inequalities and disadvantage within Housing to 2040 and this strategy has the potential to help reduce health inequalities. Key actions include preventing homelessness, improving housing standards and retrofitting homes for energy efficiency. Some of these commitments are incorporated into a new Housing Bill, which is currently progressing through the Scottish Parliament.

Yet, while the ambitions in Housing to 2040 and the linked Housing Bill are commendable, major questions are being raised about its potential to realise the strategy’s vision, as we discuss in more detail in Raising the roof: Can Scotland’s Housing to the 2040 Strategy help as an approach to reduce health inequalities? (96). Since June 2023, 13 of Scotland’s 32 Local Authorities have declared a housing emergency. In May 2024, the Scottish Parliament recognised that Scotland was facing a national housing emergency. Calls for clearer implementation plans for achieving the key commitments have been growing. For the moment, the political commitment to ensuring people have access to “affordable housing” is being questioned in light of limited resources. Assessing the implementation of Housing to 2040 will continue to be a core focus for SHERU in the coming year.

Part 1 Conclusion

This year’s analysis of Scotland’s inequality landscape reveals a mixed picture. While some indicators show modest improvements, particularly in household income and child poverty, the broader context remains one of persistent and, in some cases, deepening inequality. Life expectancy and early mortality rates have seen slight recoveries from pandemic-related declines, but these improvements are fragile and uneven. The socio-economic gradient in health outcomes, for example as seen in statistics on deaths from cancer and coronary heart disease, remains stark with only marginal narrowing of gaps between the most and least deprived areas.

The data on poverty and income suggest that targeted interventions, such as the Scottish Child Payment, are beginning to have an impact. Child poverty in Scotland has started to show signs of divergence from the UK trend, and incomes have risen for many households. However, these gains are not universal. Families with three or more children, those with disabled members, and those in rural areas have not seen falls in their poverty rate. Moreover, the failure to meet interim statutory child poverty targets underscores the limitations of current policy efforts and the need for more comprehensive and sustained action.

Housing and homelessness trends are particularly concerning. Affordable home building has slowed, homelessness applications have increased, and the quality of temporary accommodation remains inconsistent and, in many cases, inadequate. The rise in homelessness applications citing mental and physical health issues highlights the intersection of housing insecurity and poor health outcomes. Fuel poverty and poor housing conditions for some, especially in the private rented sector, further compound these challenges.

Education and early years data show limited progress. The attainment gap remains wide, and early developmental concerns among children in deprived areas are as prevalent as they were a decade ago. While there have been improvements in higher education access for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, persistent inequalities in school attendance, attainment, and early years’ experiences continue to hinder long-term outcomes.

Labour market data present a complex picture. Underlying data quality issues limit confidence in recent trends, particularly around economic inactivity. Elsewhere, earnings inequality remains entrenched, and the quality of work, especially for young adults, raises concerns about long-term financial security and wellbeing.

Overall, the evidence indicates that while certain policy measures are beginning to deliver positive outcomes, they remain insufficient to counteract deeply embedded inequalities. Structural drivers, such as housing insecurity, unequal access to secure and well-paid employment, and the enduring effects of austerity, continue to shape outcomes across education, living standards, and ultimately health. Without a more integrated and preventative approach that tackles these root causes directly, there is a significant risk that health inequalities in Scotland will become further entrenched.

As we move into Part 2 of the report, we turn our focus to the acute consequences of these inequalities among younger adult men. Their experiences offer a lens into how socio-economic disadvantage can escalate into crisis, and why early, coordinated intervention is essential to improving outcomes and reducing preventable deaths.

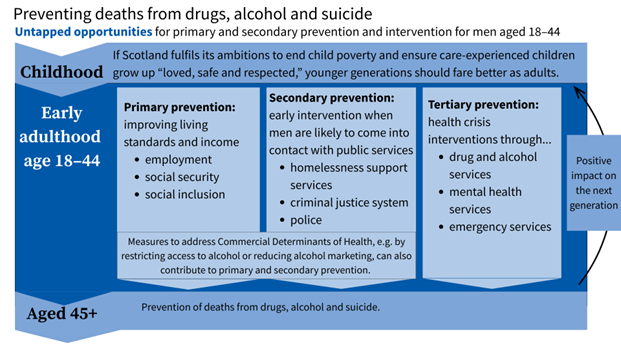

Part 2: Reducing preventable deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide – the role of socio-economic determinants

People in Scotland are more likely to die from drugs (6), alcohol (7), or suicide (8) than any other country in the United Kingdom. Even worse, Scotland has the highest drug-related mortality rate in Western Europe, and among the highest mortality rates from alcohol and suicide (97,98).

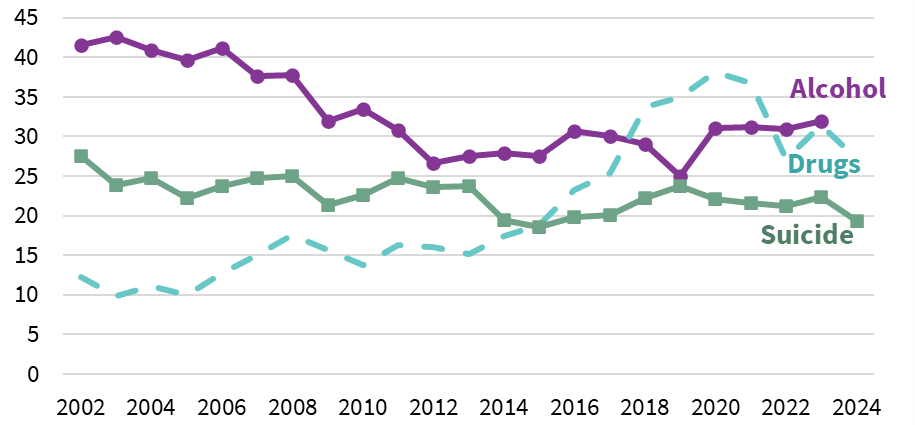

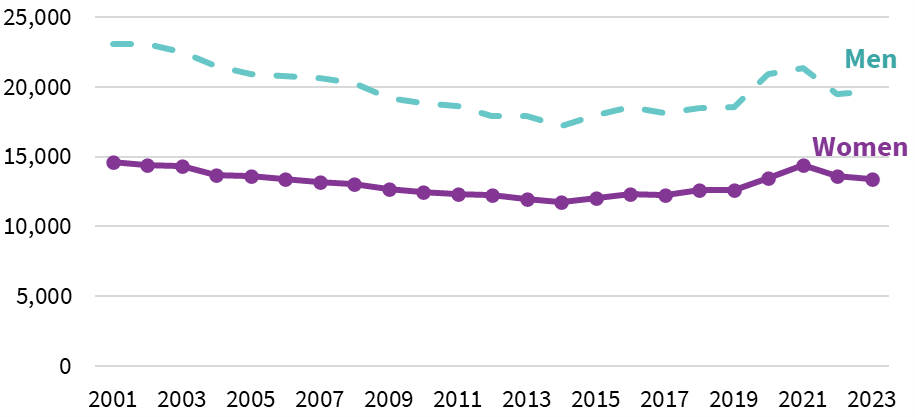

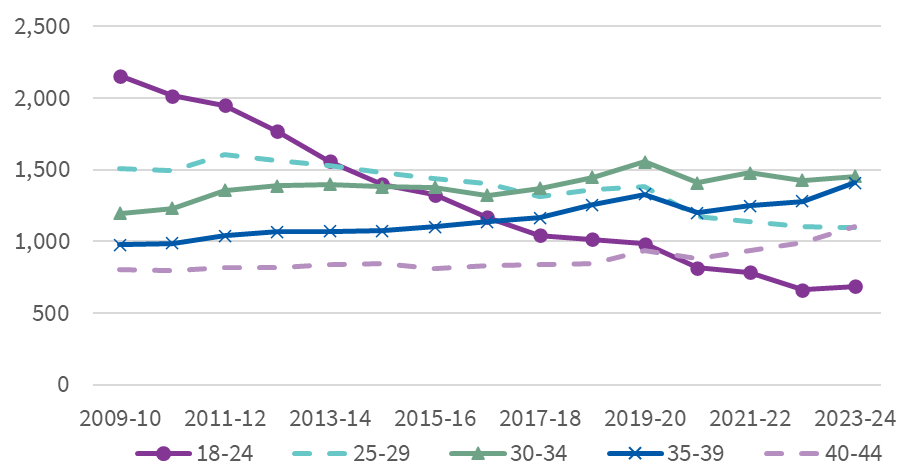

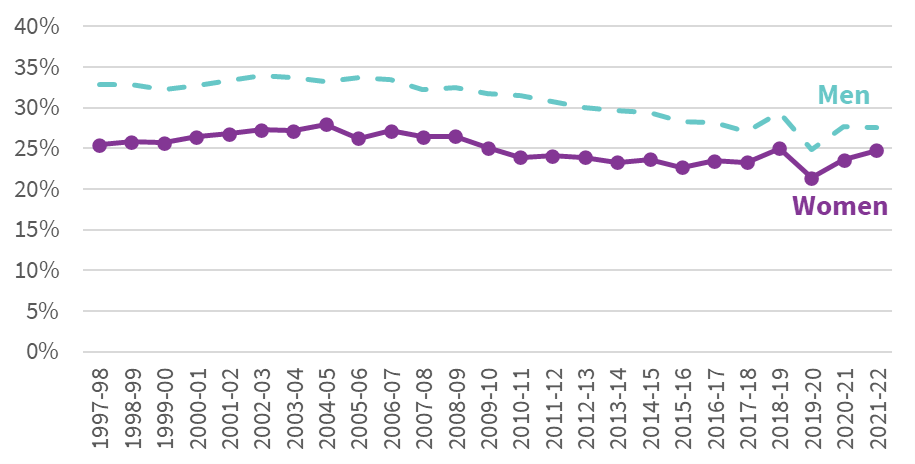

The issue is most acute for men in Scotland. In 2023, 70% of the people who died from drugs, alcohol, and suicide were male[1]. Since 2001, the cumulative effect of these three outcomes has grown over time, driven largely by dramatic increases in drug-related deaths. And, while deaths from alcohol and suicide are lower than they were nearly 25 years ago, neither has seen much change in the last decade.

Figure 6.1 Age standardised mortality rates for men from alcohol, drugs and suicide (per 100,000 population)

Source: SHERU analysis of National Records of Scotland (2024) Drug-related Deaths, Probable Suicides, and Alcohol-specific deaths (6,29,99)

Suicide, especially among younger populations, has been described as “[…] the ultimate expression of disaffection and alienation” and a “measure of our collective mental and social wellbeing” (100). Similarly, harmful consumption of alcohol and drugs have long been shown to be associated with a sense of powerlessness and social alienation (101,102). In short, where deaths from suicide, drugs and alcohol are high and rising, it suggests something is going deeply and acutely wrong for that population. For this reason, these three causes of death are sometimes collectively referred to as “deaths of despair” (103). This term highlights the fact that deaths from suicide, drugs and alcohol are often shaped by social and economic conditions that accumulate in ways that cause people to experience a strong sense of despair.

Factors associated with preventable deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide include trauma (including in childhood), poverty, poor educational experiences, unemployment, the breakdown of interpersonal relationships and homelessness (87,104–106). People who are have prior interactions with the criminal justice system are also disproportionately represented in the statistics on deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide in Scotland, with men in prison being a much higher risk of death from suicide and drug use compared to men in the wider community (107,108), suggesting that it is important to consider the role of the Scottish justice system in perpetuating harm.

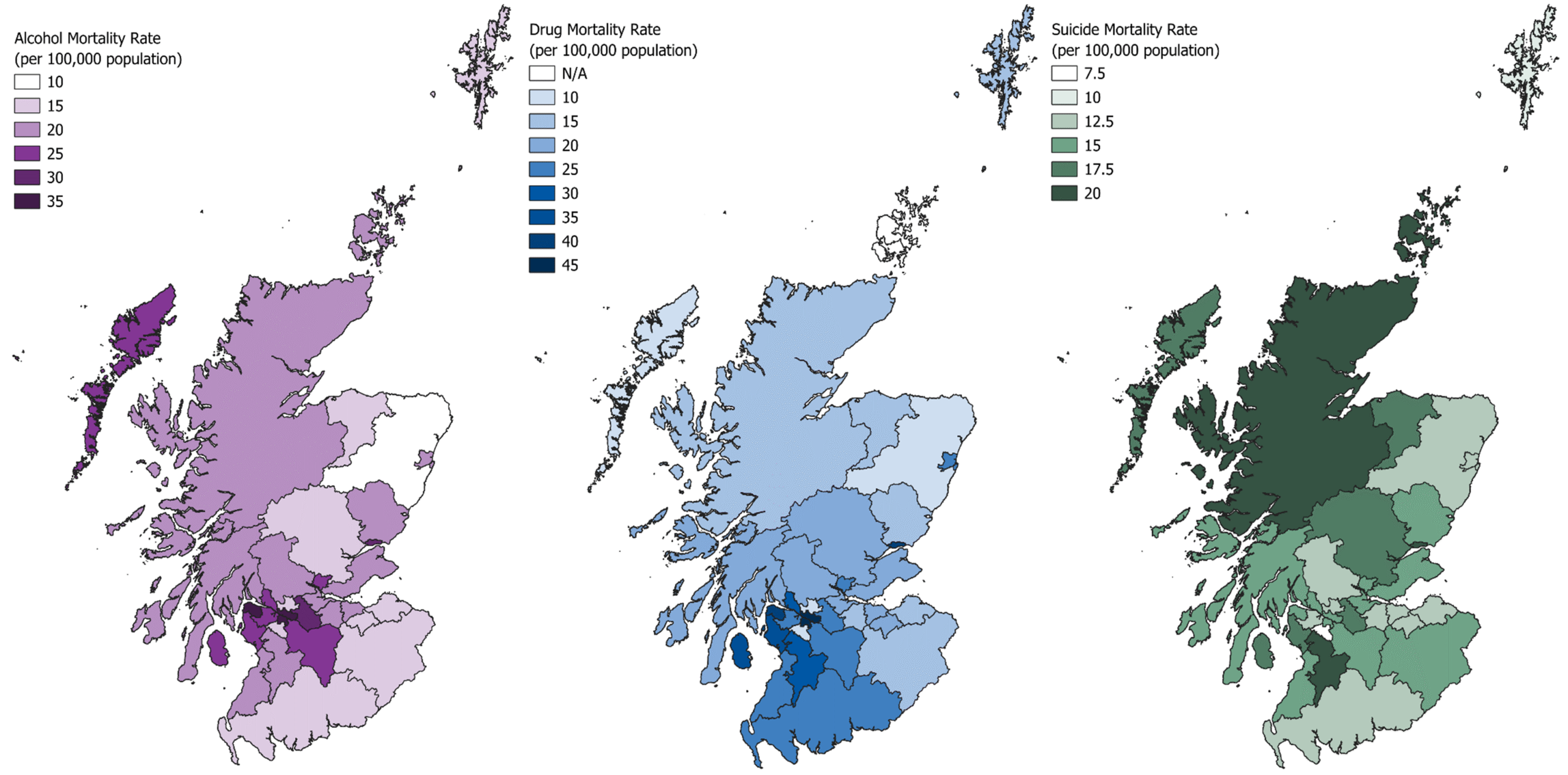

Scotland is an extreme example of the socio-economic inequalities associated with deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide: people living in the most deprived 20% of the country accounted for nearly 40% of all deaths from drugs, alcohol or suicide in 2023. Nearly a quarter of all people dying from alcohol and suicide[2] in 2023 were men living in the most deprived Scottish neighbourhoods[3] – a group which only makes up about one-tenth of the total Scottish population. (6,29,99)

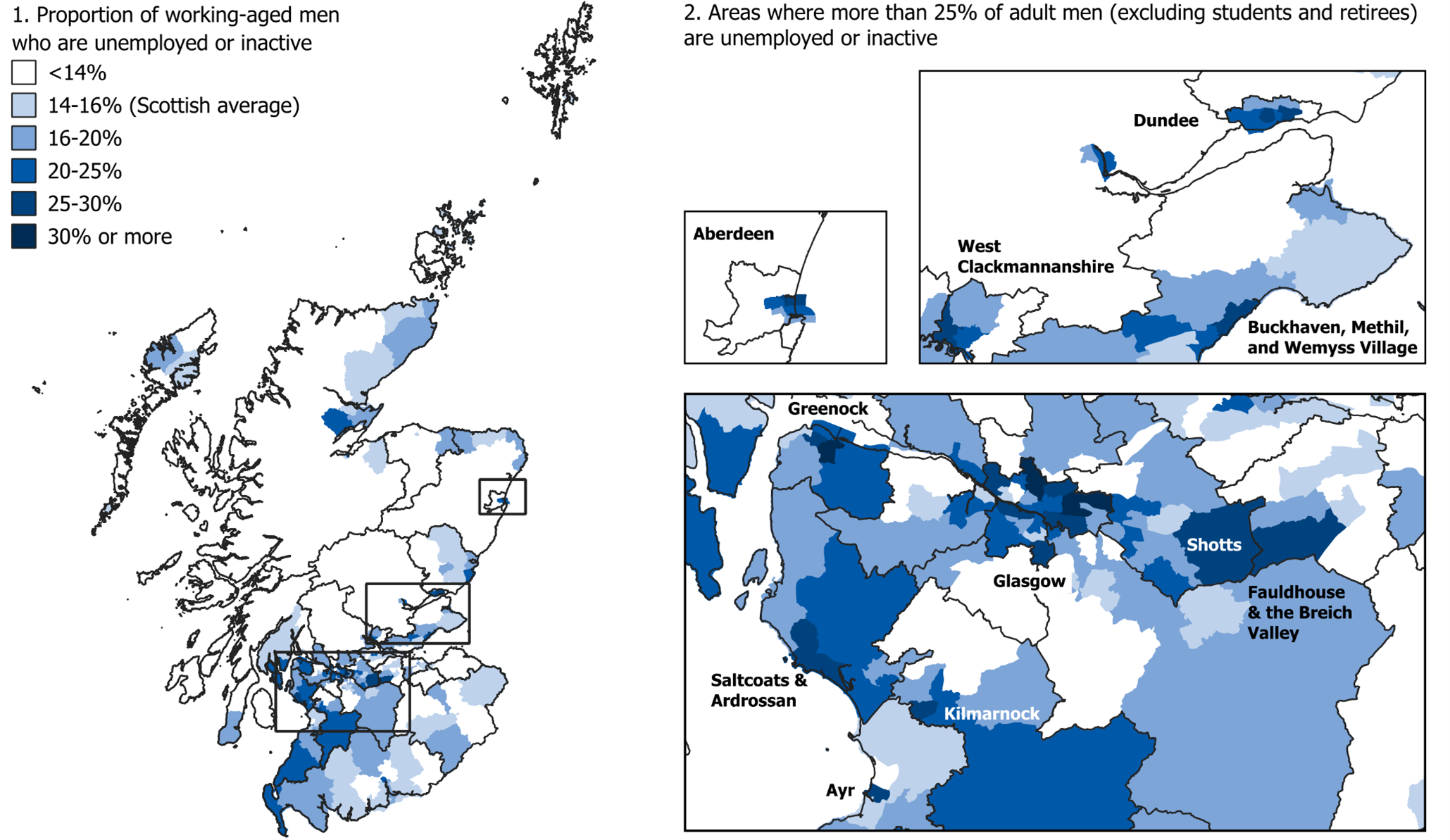

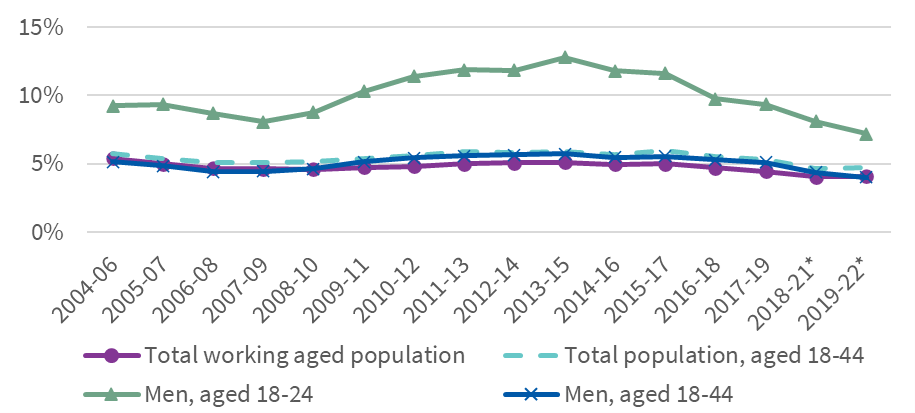

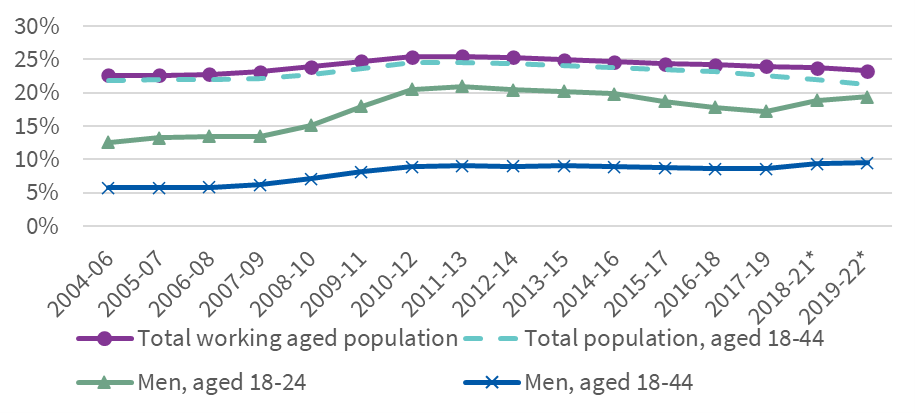

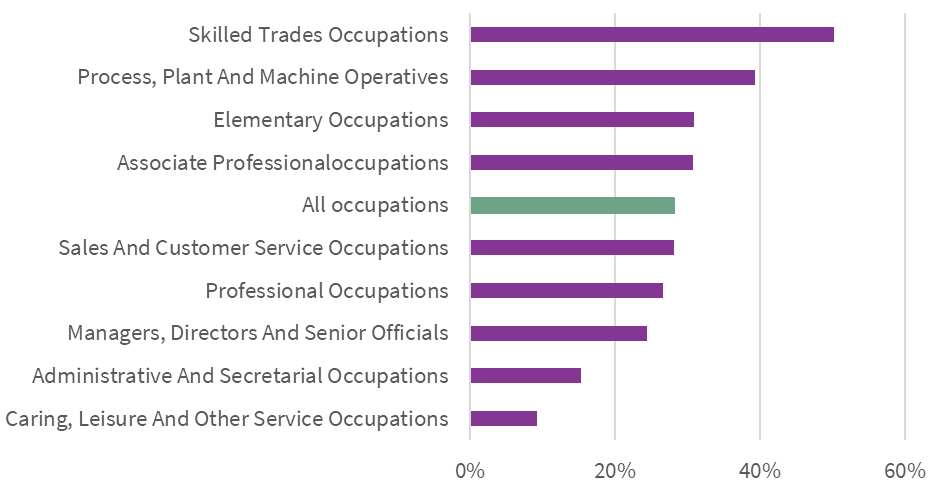

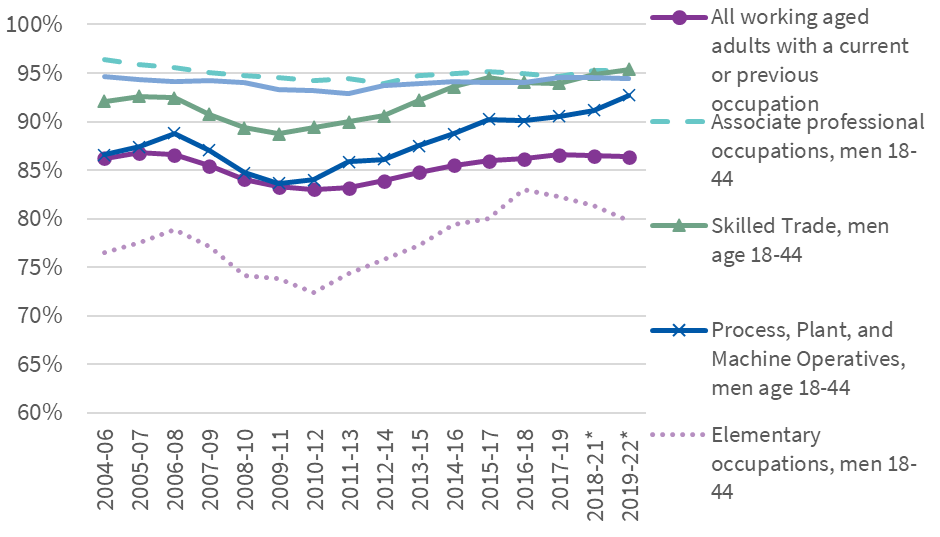

There is also a regional element to this picture. Mortality rates from suicide are highest for men living in remote small towns, followed by urban areas, and are low among rural communities. Alcohol mortality is highest in urban areas but is closely followed by remote small towns. Data for drug mortality based on urban/rural classification is not available. Regional differences are further reflected in local authority data (Map 1).