Poverty among young adult men in Scotland

A PDF version of this article can be read here. Please refer to this version of the report for Annexes 1 and 2

Summary

Young adult men facing socio-economic deprivation are at inordinately high risk of experiencing early, preventable deaths, particularly those relating to drugs, alcohol, and suicide.(1) These ‘deaths of despair’ are also more prevalent in Scotland than they are in other UK nations. Comparing poverty rates in Scotland and the rest of the UK (rUK) – and explaining the differences between them – can shed light on the underlying determinants that are responsible for these negative outcomes.

Examining relative poverty before and after housing costs have been subtracted from household income – measures which we refer to as poverty BHC and AHC respectively – the report finds:

- Poverty among young adult men in Scotland has risen sharply since the pandemic and is now higher than in rUK. AHC poverty rates were generally lower in Scotland than in rUK before the pandemic, while the opposite was the case on the BHC measure. After the pandemic, poverty rates on both measures increased by several percentage points in Scotland while falling slightly in rUK. This has led to Scotland overtaking rUK on the AHC measure; the difference is not statistically significant, although significant differences do emerge when examining particular sub-groups. Meanwhile the gap in BHC rates has widened to become statistically significant in the latest period (2021-24).

- The post-pandemic rise in poverty among young adult men has not affected women in the same age bracket, nor has it been observed to the same extent in any other UK region. Indeed, the divergence in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK among young adult men has also represented a divergence in poverty rates within Scotland between young adult men and young adult women, who previously faced relatively similar risks of living in poverty. The AHC poverty rate among young adult men is now higher in Scotland than in any other UK region, while the BHC poverty rate is second only to Wales, having previously been around the cross-regional average.

- The increase in poverty among young adult men, and the resulting gap with rUK, was driven by an increase in poverty risk among those aged 18-24, those who are out of work, and those who are single without children. These men often live with other adults such as parents or housemates, who provide the majority of household income. The income of these other adults has reduced in Scotland – particularly in terms of earnings, reflecting a real-terms fall in hourly wages – but not in rUK. Further research is needed to understand why this specific group has experienced wage stagnation in recent years.

These results pose a major concern from a health equity perspective. The longer that individuals remain in poverty, the higher their risk of experiencing adverse health conditions, and the greater challenges they will face as they move further into working age. The results also reinforce our previous finding that young adult men fall into a blind spot in the Scottish policy landscape. There is a need to better understand the circumstances of this group to inform joined-up, preventative action, rather than only treating negative health outcomes as crises arise later. We will be undertaking further work to more fully understand the results of this report and to draw out the implications for policy.

Introduction

Poverty rates can vary across time and space for a wide range of reasons. Decomposition analysis is one way to identify the factors that are driving such variations. This method disaggregates a variation in poverty rates between two groups or two time periods into composition effects (variations in the makeup of the population, with different characteristics associated with different poverty risks) and incidence effects (variations in poverty risk for each characteristic). The method has previously been used by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, and the Scottish Government, as well as SHERU. (2–5)

When performing this kind of analysis, we must be mindful that apparent variations in poverty rates – whether across time or across space – do not always reflect the real world. Poverty statistics are derived from survey samples, which are scaled up to represent the population. As a result, erroneous variations can arise simply because certain households happened to be surveyed rather than others. Testing for statistical significance allows us to determine whether we can be confident that observed patterns reflect reality – as far as the survey design allows – rather than this kind of sampling error. In recent decades, a steady decline in the size of the survey sample has made it increasingly difficult to establish statistical significance.(5) Note however that if a pattern is not statistically significant, this does not imply that the pattern is the opposite of what we observe – only that we cannot be confident either way.

Throughout this report, we define poverty in relative terms, as having net equivalised household income below 60% of the UK median. In this context, equivalisation is a process of adjusting household income to enable consistent comparisons across different household types, which will tend to have different resource requirements. We examine relative poverty both before and after housing costs have been subtracted from income. Although after-housing-cost (AHC) poverty is the official measure, comparing this with before-housing-cost (BHC) poverty can help establish whether observed patterns pertain to housing costs or income narrowly defined.

Most of the analysis in this report is based on comparing poverty rates in Scotland and rUK. Clearly, rUK is an arbitrary aggregation, which is likely to conceal important variations between regions. The idea is not to generalise across this category, but rather to provide a comparison with Scotland. There will also be important variations within Scotland, but unfortunately the data do not allow for analysis at a lower geographical level.

Note also that our population of interest is defined solely in terms of age (18-44) and sex (male). It therefore includes 18- and 19-year-old men who are technically classified as dependents for purposes of the benefit system – namely those who are in full-time training or education and still living with their parents or guardians. Conversely, it excludes any individuals who identify as men but whose sex is not reported as male. The underlying survey data also excludes people who are homeless or in custody – populations that are strongly associated with poverty and in which young men are overrepresented. (6,7)

The report firstly examines trends in poverty among young adult men, in particular the difference in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK, before decomposing these differences in the following section. The annexes provide supplementary outputs.

Trends in poverty

Key points

- The AHC poverty rate among young adult men in Scotland has increased since the pandemic to overtake the equivalent rUK rate, although the difference is not statistically significant.

- A similar trend was observed on the BHC measure; and since the BHC poverty rate among young adult was already higher in Scotland than rUK, this has opened up a statistically significant difference in the latest period (2021-24).

- The increase in poverty was specific to young adult men in Scotland: it was not observed to the same extent among women in the same age bracket or among young adult men in any other UK region.

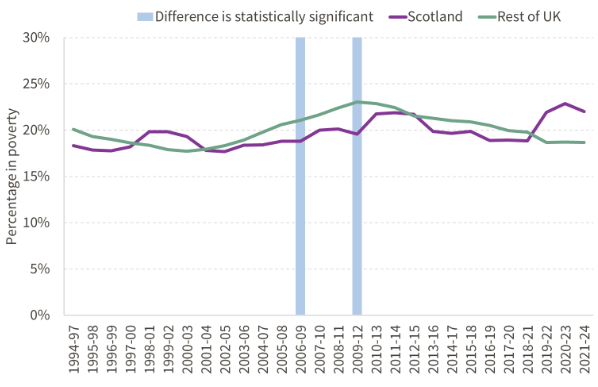

Figure 1 shows AHC poverty rates for men aged 18-44 in Scotland and rUK. Poverty was lower in Scotland than rUK in most time periods since the early 2000s, but the difference was only significant in a statistical sense in 2006-09 and 2009-12. Since the pandemic, however, this group experienced a steep rise in poverty in Scotland that was not reflected in rUK, with the result that the pattern has inverted: poverty among this group has been higher in Scotland than rUK since 2019-22, although the difference has not been statistically significant. Notably, AHC poverty is now almost as prevalent among men aged 18-44 (22%) as it is among children (23%). There has however been a reduction in the latest time period.

Figure 1: Proportion of non-pensioner households with £1,000 or more in liquid savings, by equivalised income quintile

Based on the methodology outlined by DWP, 2025, Measuring Uncertainty in HBAI Estimates. Relative poverty defined as having net equivalised household income below 60% of the UK median. Significance measured at 5% level. Data for 2020-21 has been excluded owing to data quality issues. Source: FAI analysis of DWP, Households Below Average Income

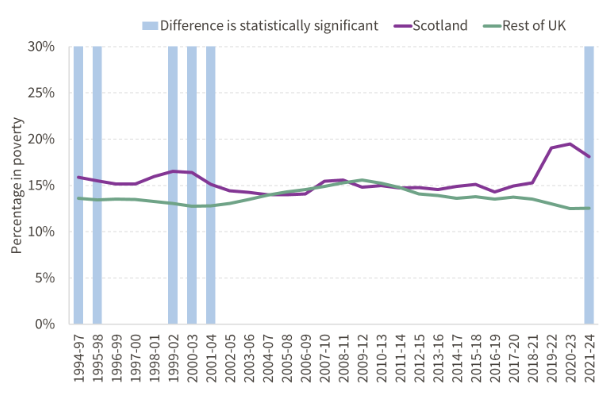

Figure 2 shows the same comparison for BHC poverty. A similar pattern has been observed since the pandemic, with a steep rise in poverty observed in Scotland but not rUK. However, as the BHC poverty rate among young adult men had already been higher in Scotland than rUK since the mid-2010s, the resulting gap is wider, with a statistically significant difference observed in the latest time period (2021-24).1 The emergence of a statistically significant difference repeats the pattern observed before the early- to mid-2000s, when the poverty rate among this group, along with the population as a whole, was higher in Scotland than rUK.

Figure 2: Percentage of men aged 18-44 in relative poverty before housing costs, three-year average

Based on the methodology outlined by DWP, 2025, Measuring Uncertainty in HBAI Estimates. Relative poverty defined as having net equivalised household income below 60% of the UK median. Significance measured at 5% level. Data for 2020-21 has been excluded owing to data quality issues – averages including this year are two-year averages. Source: FAI analysis of DWP, Households Below Average Income

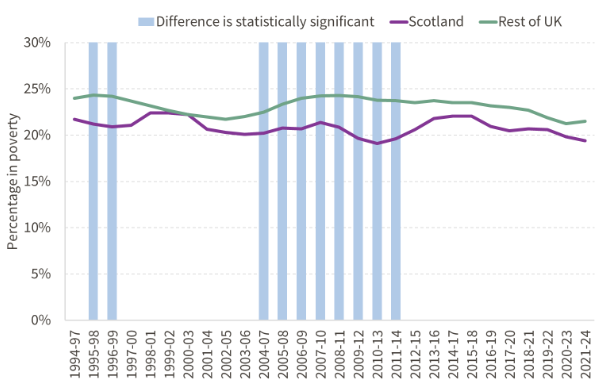

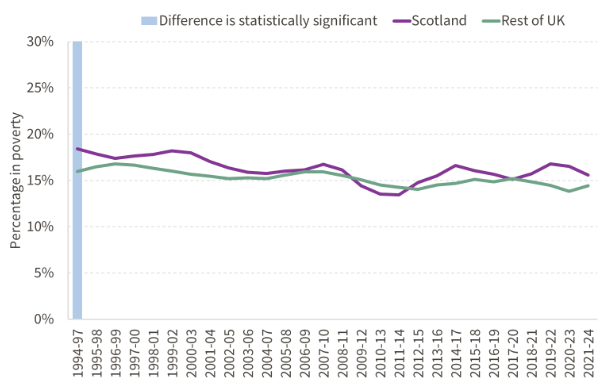

The post-pandemic rise in poverty among young adult men is not evident among women in the same age bracket, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. AHC poverty rates among women aged 18-44 have been lower in Scotland than rUK since the beginning of the data series in the mid-1990s, although the difference has not been statistically significant since the mid-2010s. Meanwhile, BHC poverty rates among young adult women in Scotland and rUK have closely tracked each other since the mid-2000s. This implies that there are factors at play that are specific to men. Indeed, the post-pandemic divergence in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK among young adult men has also represented a divergence in poverty rates within Scotland between young adult men and young adult women, who previously faced relatively similar risks of living in poverty.

Figure 3: Percentage of women aged 18-44 in relative poverty before housing costs, three-year average

Based on the methodology outlined by DWP, 2025, Measuring Uncertainty in HBAI Estimates. Relative poverty defined as having net equivalised household income below 60% of the UK median. Significance measured at 5% level. Data for 2020-21 has been excluded owing to data quality issues. Source: FAI analysis of DWP, Households Below Average Income

Figure 4: Percentage of women aged 18-44 in relative poverty before housing costs, three-year average

Based on the methodology outlined by DWP, 2025, Measuring Uncertainty in HBAI Estimates. Relative poverty defined as having net equivalised household income below 60% of the UK median. Significance measured at 5% level. Data for 2020-21 has been excluded owing to data quality issues. Source: FAI analysis of DWP, Households Below Average Income

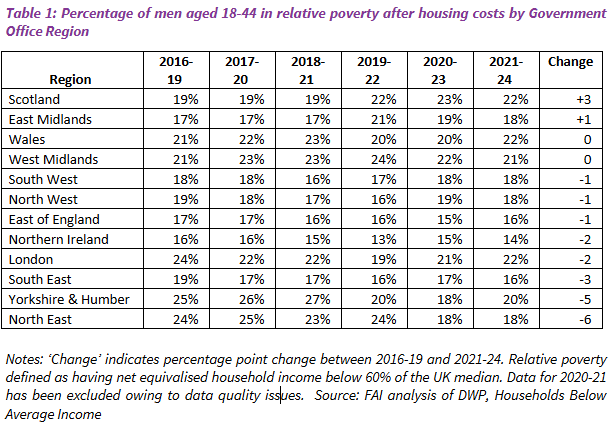

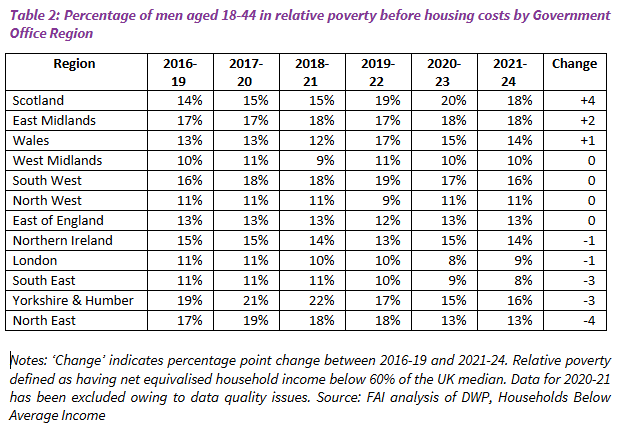

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the magnitude of the increases are also unique to Scotland. Among the other twelve ‘government office regions’ in the UK, six saw increases in BHC poverty among young adult men between 2016-19 and 2019-22, while four saw increases in AHC poverty. However, by 2021-24, the AHC poverty rate remained higher than 2016-19 in only one region other than Scotland, namely Wales, with the East Midlands also recording an elevated poverty rate when measured BHC; and in neither of these regions were the increases as severe as they were in Scotland. As a result, having previously been around the middle of the pack, the AHC poverty rate among young adult men is now higher in Scotland than any other UK region, while the BHC poverty rate is second only to Wales. It therefore appears that the factors underlying the post-pandemic increase are not only specific to young adult men, but are particularly acute for young adult men in Scotland.

Decomposition

Key points

- The difference in the BHC poverty rates between Scotland and rUK among young adult men in 2021-24 primarily reflects a higher risk of living in poverty in Scotland among men aged 18-24, those out of work, and those who are single without children.

- On these dimensions, differences between Scotland and rUK in the composition of young adult men do not play a large role in explaining the difference in poverty rates, which is driven instead by a higher incidence of poverty among young adult men with these characteristics in Scotland.

- Similar results are found when decomposing the increase in BHC poverty among young adult men within Scotland between 2016-19 and 2021-24, implying that these are new differences that have emerged since the pandemic.

To investigate why poverty among young adult men is higher in Scotland than rUK – and why this pattern has emerged since the pandemic – we perform our decomposition analysis on three key sets of characteristics: individual work status, age band, and living situation. Work status provides an indication of an individual’s sources of income and helps to establish whether the difference in poverty is related to labour-market factors. Age is also a crucial piece of information, not least because the experience of those just entering the labour market is likely to differ substantially from those further on in their working lives. Meanwhile, an individual’s living situation – that is, whether they live with a partner, children, or anyone else – helps us understand whether they are benefitting from other sources of household income and conversely whether they are providing for dependents.

As the difference in poverty rates is statistically significant BHC but not AHC, we focus on BHC poverty in this analysis. The fact that similar increases in poverty were observed BHC and AHC also implies that the contributing factors relate to income rather than housing costs, and focusing on BHC poverty allows us to examine these factors more directly. However, for the same reason, the results would be similar if we instead examined AHC poverty.

Decomposing changes in poverty rates over time requires us to additionally select the time periods to compare. The increase in poverty among young adult men in Scotland began earlier on the BHC measure than it did on the AHC measure, namely from 2017-20. We therefore use 2016-19 as the base period, representing the latest point before the increase began. Although both AHC and BHC poverty fell in Scotland in 2021-24, we use this as the comparison period, both to ensure that the analysis is current and because the previous period includes 2020-21, for which data is omitted due to quality issues.

Note that the increase in poverty among men aged 18-44 in Scotland between 2016-19 and 2021-24 was not statistically significant before or after housing costs. This means we can be more confident in explaining the differences between Scotland and rUK than we can be in explaining the changes over time, even though the two are closely related. It is still possible to decompose the changes, but more caution is needed when interpreting the results.

Differences between Scotland and rUK

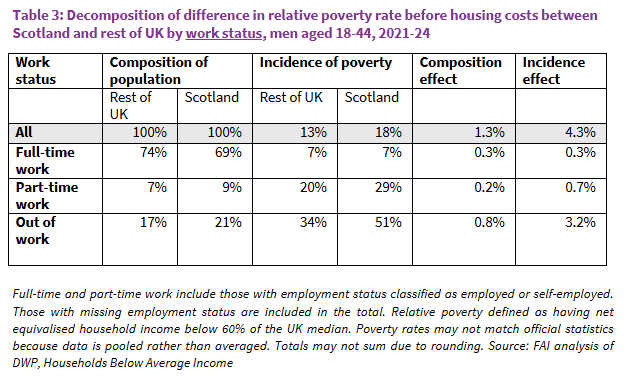

Table 3 decomposes the difference in poverty rates among men aged 18-44 in 2021-24 by work status. There are some differences in composition, with Scotland containing a lower proportion of full-time workers and higher proportions in the other categories. However, the main differences lie in the incidence of poverty – particularly among those who are out of work, half of whom are in poverty in Scotland as compared to one-third in rUK. Accordingly, the incidence effect among this group explains most of the overall difference in poverty rates.

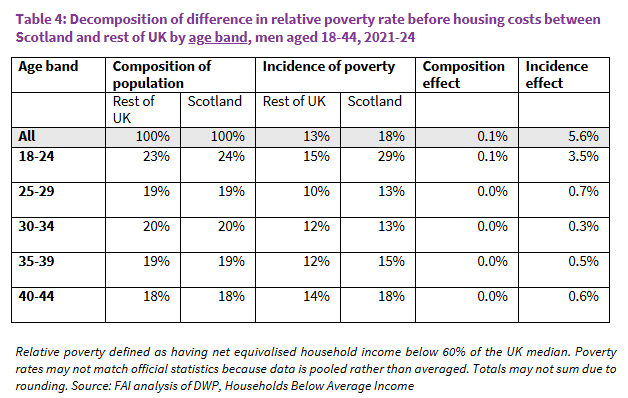

Table 4 presents the same decomposition across age bands. Any compositional differences are marginal, and accordingly the composition effect is minor. While poverty rates are higher in Scotland than rUK across age bands, the incidence effect is concentrated among 18-24 year-olds, for whom the poverty rate is almost twice as high in Scotland (29%) as it is in rUK (15%).

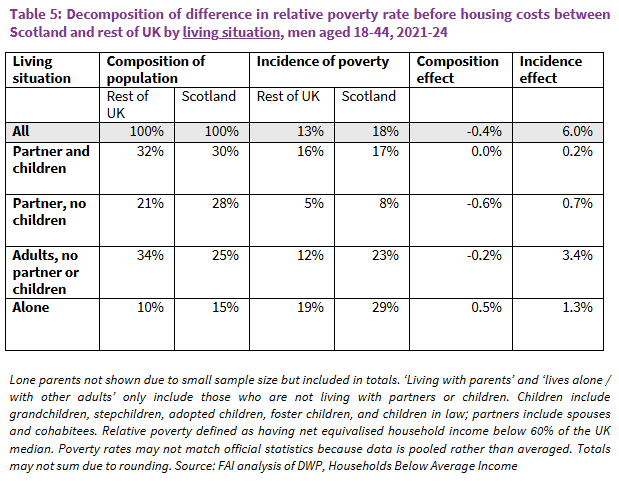

Table 5 repeats the decomposition by living situation. Differences in composition are again relatively minor – in fact they are cumulatively negative, meaning that on this dimension the entire difference in poverty rates is explained by the incidence effect. Furthermore, most of this effect derives from men who are living with adults other than partners, such as parents or housemates. These men face a poverty rate that is nearly twice as high in Scotland (23%) as it in rUK (12%.) A smaller but still substantial incidence effect is detected among those living alone, who also generate a composition effect by representing a larger share of young adult men in Scotland than in rUK. Note that individuals who are homeless, serving prison sentences, or living outwith private residences for other reasons are not included in the data.

Changes over time

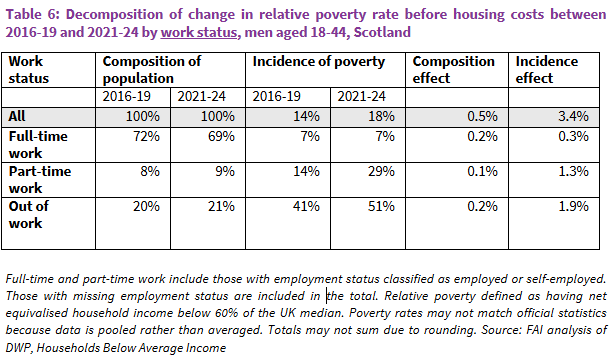

Table 6 decomposes the change in poverty rates among men aged 18-44 between 2016-19 and 2021-24 in Scotland by work status. As per the comparison with rUK, most of the change in the poverty rate is explained by the incidence effect, with relatively minor changes in composition. However, while the out-of-work group still shows the largest incidence effect, we also see a notable effect among part-time workers, with a doubling of the poverty rate among this group accounting for about one-third of the overall increase. The implication is that this poverty rate was previously lower in Scotland than in rUK, so that the increase contributes more to the change within Scotland than it does to the difference with rUK in the latest period.

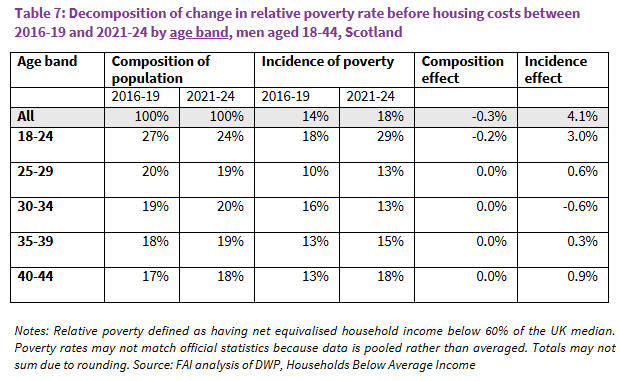

Table 7 presents the same decomposition across age bands. The results are similar to the rUK comparison: the change in poverty rate among young adult men is entirely explained by the incidence effect, with this effect mainly albeit not exclusively experienced by 18-24 year-olds.

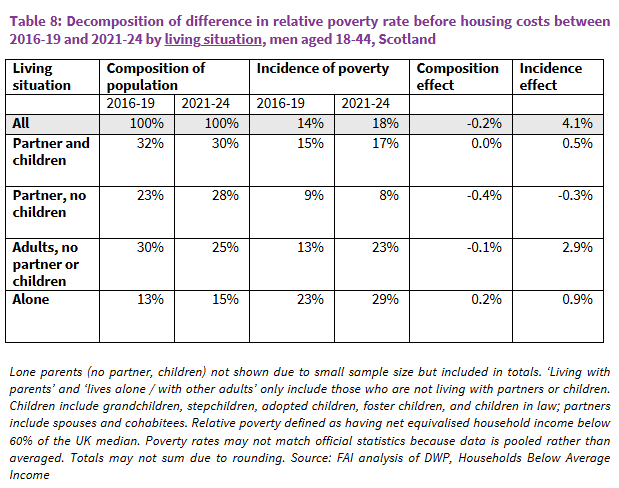

Table 8 repeats the decomposition by living situation. The results likewise mirror the comparison with rUK: the entire increase in poverty among young adult men since the pandemic is explained by the incidence effect, the majority of which is concentrated on men living with other adults but not a partner or children. Again, those living alone also show a notable incidence effect, reflecting an increase in poverty risk over time.

Discussion

Key points

- The young men who face a higher poverty risk in Scotland as compared to rUK most acutely – those who are on the younger end of the age range, those who are out of work, and those who are single without children – will tend to have little income of their own. Instead they will tend to rely on the income of other adults in the household, such as parents and housemates.

- On average, income from these other household members has reduced in Scotland since before the pandemic and the ensuing cost-of-living crisis, driven by a real-terms fall in hourly wages among full-time workers that was not reflected in rUK.

- Further research is needed to determine why this specific group – those living with young adult men in Scotland – has experienced wage stagnation. The findings are nevertheless concerning from a health equity perspective and provide further evidence of a policy blind spot around young adult men in Scotland, underlining the need for preventative action.

The analysis in this report has shown that the difference in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK among men aged 18-44 primarily affects those on the younger end of the range, those who are out of work, and those who are single without children but living with other adults, with the underlying factors appearing to relate to income rather than housing costs. Similar results were found when decomposing the change across time, indicating that the difference in poverty risk among these individuals has appeared since the pandemic. In other words, these changes in the incidence of poverty have been specific to Scotland, resulting in a divergence with rUK. This can be confirmed mathematically by combining the two decompositions, as shown in Annex 1.

We also find that differences in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK become statistically significant even after housing costs when focusing on young men who are single without children and those who are out of work, although not when focusing on those who are aged 18-44 and those who are single without children but also living with other adults. There is a trade-off here between magnitude and precision: although particular sub-groups show larger differences, making it easier to establish statistical significance, they necessarily correspond to smaller samples, making it more difficult to do so. However, the same overall pattern is observed for each of these subgroups as it is for young men as a whole.

While these results reveal proximate causes, they also raise further questions. Individuals who are out of work will clearly have no earnings of their own. Their benefit entitlements are also likely to be limited if they are economically inactive rather than unemployed – which is the case for the majority of those who are out of work – and if they do not have children. If any these individuals are not in poverty, they must therefore be relying largely on the income of other adults in the household. By implication, the increase in poverty observed among young adult men in Scotland must reflect a reduction in the income of these other adults – specifically parents and housemates as opposed to partners, based on our decomposition results – rather than their own income.

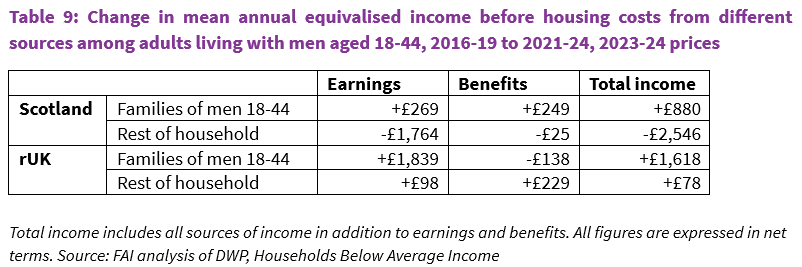

This is verified in Table 9, which distinguishes between the income received by young adult men’s own family units (including themselves and their partners) and the income received by other household members (such as parents and housemates).2 The table shows that while the incomes of their families increased in real terms in both Scotland and rUK between 2016-19 and 2021-24, on average this increase was around twice as large in rUK. Yet the difference is even starker when it comes to the rest of the household, for whom average income grew marginally in rUK while falling by around £2,500 per year in Scotland. Most of this fall reflected a real-terms drop in earnings rather than benefits.

Mathematically, real earnings among other household members could have fallen for three reasons: a reduction in the proportion of adults who are in work, a reduction in their working hours, or a reduction in their real hourly wages. To discern which of these is causing the increase in poverty, we can repeat the decomposition analysis on the work status of adults living in the same households as men aged 18-44 (see Annex 2). Poverty also increased among these individuals – which is unsurprising given that poverty is measured at the household level – though by less than for young adult men themselves.

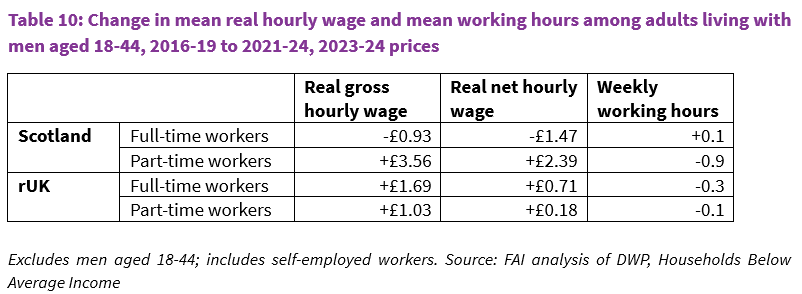

The decomposition indicates that changes in employment patterns – that is, people moving between full-time work, part-time work, and being out of work – explain only a small fraction of the overall increase in poverty. It therefore appears that the fall in earnings among adults living with young adult men reflects a fall in real wages rather than a fall in working hours or employment levels. This is supported by Table 10, which shows that, although a reduction in average working hours was observed among part-time workers in Scotland, which was larger than the reduction observed in rUK, more notable was the real reduction in average hourly wages among full-time workers, by nearly £1.50 per hour in net terms.3 This reduction was not mirrored in rUK or among part-time workers in Scotland among the adults living with young men.

Further research would be needed to understand why wages have failed to keep pace with inflation for this specific group of individuals, namely adults in Scotland who are working full-time and living with young men. However, it is clear that the explanation must lie in the interrelations between these geographic, economic, and demographic factors. One account that is consistent with the data – although certainly not proved by it – is as follows.

Young men in deprived areas face a lack of labour-market opportunities, causing them to stay out of work when they would otherwise be starting their careers and to either continue living with parents or to move in with others rather than forming their own households. As demonstrated by the lack of composition effects in our results, this is not a new problem since 2016-19, nor is it unique to Scotland. The literature does suggest, however, that co-residence has increased across the UK and beyond in recent decades, coinciding with reduced marriage and parenthood – and that this trend is particularly pronounced among men and among low-income households.(8,9)

Some of these same geographical areas – particularly in Scotland – could have relied for employment on sectors that lacked the institutions to protect workers from real wage cuts amidst the period of high inflation that followed the pandemic. Thus, the pay of the other adults in the household fell in real terms, pulling them – as well as the young men that live with them – into poverty. On the other hand, women in the same age bracket may have been shielded from these effects by the very factors that make women less likely to co-reside, such as differing patterns of household formation and labour-market participation.

Ultimately, though, this is a speculative account, and a definitive explanation is beyond the scope of this report – not least because the underlying data do not allow us to examine geographical dimensions below the Scotland level. Meanwhile, information on sector is limited by sample sizes, although it is at least possible to observe that nearly half of the rise in poverty among adults who living with young men is explained by an increase in poverty risk among those working in health and social care and in education, despite these industries together representing only around one-quarter of the demographic group (see Annex 2). We also see that incidence effects are concentrated in the private sector – even though health and education are dominated by the public sector – in line with evidence that public-sector pay has grown faster in Scotland than in rUK in recent years.(10)

It is always possible that patterns such as those discovered in this report are the result of issues with the representativeness or accuracy of the underlying survey data. To the extent that these statistical biases vary across time and space, they could in theory result in a spurious divergence in poverty rates between Scotland and rUK. Validating our findings against other data sources is not straightforward,4 but we do not have any reason to believe that the sample is unreliable in this way, and our significance tests at least provide confidence that the difference in poverty rates is not the result of random variation within the sample. We note, however, that the DWP are planning a programme of work to improve the data, including by linking records to administrative benefit data and by introducing a revised grossing regime, the method by which the sample is scaled up to the population.(11) We expect this to result in appreciable changes to poverty rates, though the implications for this analysis cannot be anticipated.

Whatever their ultimate explanation, the results of the analysis are concerning for many reasons. From a health equity perspective, an increase in poverty among young adult men is likely to exacerbate the issues that they already face. Being out of work may independently increase their risk of experiencing adverse health conditions, particularly if sustained over the long run. There is also evidence to suggest that co-residence with parents into adulthood can negatively impact career development among young adult men, although findings are mixed.(12) The results of this analysis therefore act as an early warning sign of a further deterioration in outcomes among this group. We will continue to monitor these outcomes along with the poverty rate itself, not least to determine whether the reduction in poverty seen in the latest period marks the beginning of a downward trend.

The results also provide further evidence of a policy ‘blind spot’ when it comes to young adult men who face poverty and deprivation, reinforcing the need to better understand their circumstances and build the infrastructure for evidence-led action.(1) Although a subset of these individuals face a compounding set of issues across work, housing, justice, and mental health, they are typically supported only when they face an acute crisis rather than through preventative, joined-up policies. Young adult men now face a similar poverty rate as children, yet there is no central, overarching strategy for tackling the disadvantages that they experience. We will be undertaking further work to more fully understand the results of this report and to draw out the implications for policy.

References

1. Catalano A, Congreve E, Jack D, McHardy F, Smith K. 2025 Inequality Landscape [Internet]. 2025 Sep [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Available from: https://scothealthequity.org/inequality-landscape-2025/

2. Scottish Government. Tackling child poverty – progress report 2024-2025: annex C – decomposition analysis of the child poverty statistics [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/tackling-child-poverty-progress-report-2023-2024-annex-c-decomposition-analysis-child-poverty-statistics/

3. Congreve E. Poverty in Scotland 2019 | Joseph Rowntree Foundation [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.jrf.org.uk/poverty-in-scotland-2019

4. Brewer M, Goodman A, Shaw J, Sibieta L. Poverty and inequality in Britain: 2006 [Internet]. IFS; 2006 Mar [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Available from: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/poverty-and-inequality-britain-2006

5. Thompson S. Comparing poverty rates in Scotland and the rest of the UK [Internet]. Scottish Health Equity Research Unit; 2026 Jan [cited 2026 Feb 4]. Available from: https://scothealthequity.org/comparing-poverty-rates-in-scotland-and-the-rest-of-the-uk/

6. Scottish Government. Scottish Prison Population Statistics 2024-25, Supplementary Table B2 [Internet]. 2025 Nov [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-prison-population-statistics-2024-25/

7. Scottish Government. Homelessness in Scotland: update to 30 September 2025, Table 15b [Internet]. 2026 Feb [cited 2026 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/homelessness-in-scotland-update-to-30-september-2025/

8. Boileau B, Sturrock D, Atkinson I. Hotel of Mum and Dad? Co-residence with parents among those aged 25–34 [Internet]. Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2025 Jan [cited 2025 Dec 17]. Available from: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/hotel-mum-and-dad-co-residence-parents-among-those-aged-25-34

9. Esteve A, Reher DS. Rising Global Levels of Intergenerational Coresidence Among Young Adults. Popul Dev Rev. 2021;47(3):691–717.

10. Cribb J, Domínguez M, O’Brien L. Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2025 [cited 2026 Jan 9]. Public sector pay up by 5% in Scotland since 2019, in contrast to no UK-wide increase. Available from: https://ifs.org.uk/news/public-sector-pay-5-scotland-2019-contrast-no-uk-wide-increase

11. Department for Work and Pensions. GOV.UK. [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Family Resources Survey: release strategy. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/family-resources-survey-release-strategy/family-resources-survey-release-strategy

12. Saydam A, Raley K. Slow to launch: Young men’s parental coresidence and employment outcomes. J Marriage Fam. 2024;86(4):1009–33.

For Annexes 1 and 2, please refer to the PDF version of this report.