International Definitions and Measures of ‘Affordable Housing’ and Current Local Practices in Scotland

This report can be accessed as a PDF here.

Executive Summary

Safe, stable, and affordable homes are fundamental building blocks for health, wellbeing, and wider life outcomes. Housing precarity—such as insecure, poor-quality, or unaffordable housing—has well-evidenced negative impacts on health and wellbeing. The fact that Scotland is currently experiencing a housing emergency, as declared by the Scottish Government in May 2024, is therefore of major concern when it comes to population health and health inequalities.

The Scottish Government’s housing strategy, Housing to 2040, places a strong emphasis on affordable housing, with specific affordable homes targets. Yet, there is currently no agreed way of defining and measuring affordable housing in Scotland. The strategy included a commitment to work with stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of affordability and a Scottish Government Housing Affordability Working Group, chaired by Professor Ken Gibb, is due to report imminently. Ahead of this review, and in support of our broader assessment of the potential for Housing to 2040 to help reduce health inequalities, this briefing delves into some of the options for defining and measuring affordable housing. SHERU’s focus on health inequalities means we are particularly concerned with understanding how measures of affordable housing link to housing availability for low income, and very low income, households. We therefore focus particularly on how well definitions and measures capture the challenges facing low income households across all sectors (so homeowner, private rental and social housing).

Part 1 provides an accessible overview of common ways of measuring housing affordability and considers some of the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ of each option, paying attention to the extent to which each measure captures inequalities in access to affordable housing. Our review of definitions and measures is grounded in a 2018 UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) report, which sought to critically appraise measures and definitions of affordable housing in use internationally. Where possible, we also sought to update this overview.

The two most common measures both involve the calculation of a ratio. The most widely used, and often the easiest to calculate, involves a ratio of the average market value of properties in an area to average incomes/earnings. This measure tells us little about the affordability of housing for people in the private rented sector or in social housing. The second most common measure compares a household’s income with their housing costs, which is sometimes represented as a proportion or percentage. This measure captures people across sectors (homeowners, private sector renters and those in social housing) but still obscures a large amount of variation in the circumstances of different households. From an equity perspective, the less common approach of measuring residual income, after housing costs have been accounted for, is potentially more useful. While all three measures are relatively straightforward to calculate nationally, key data are often unavailable locally.

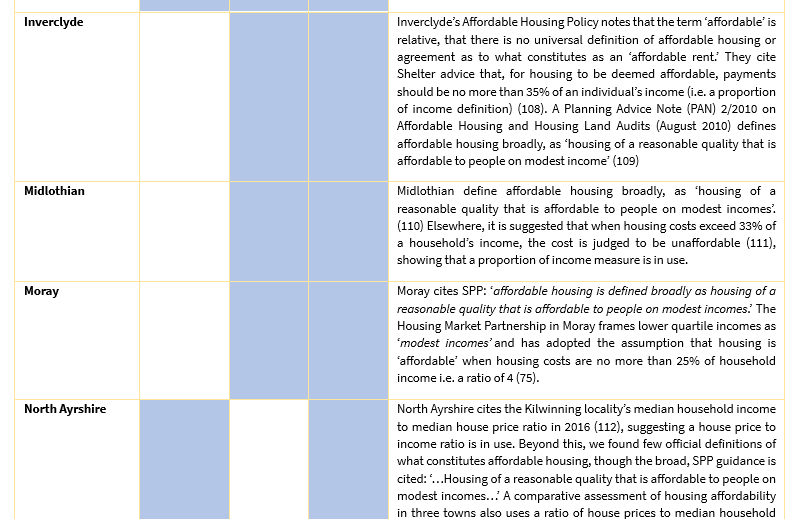

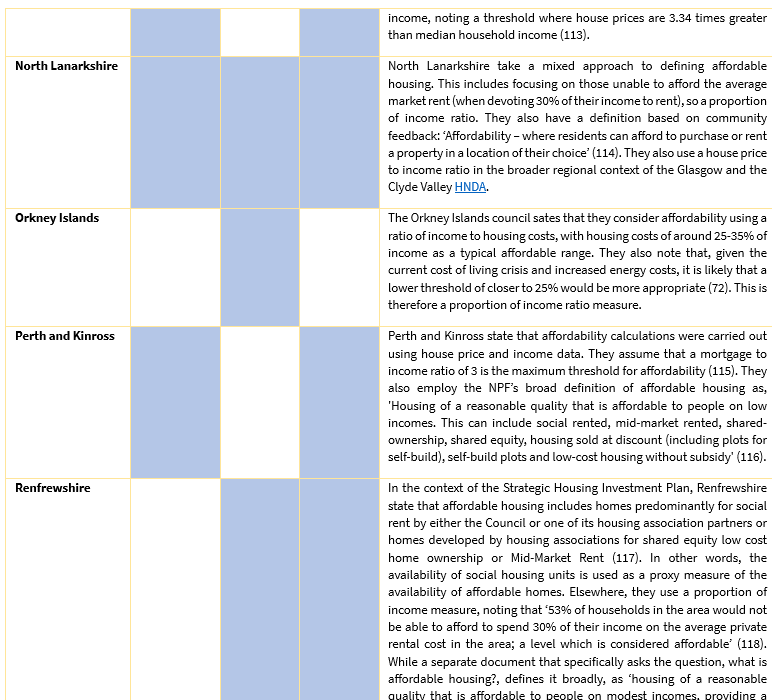

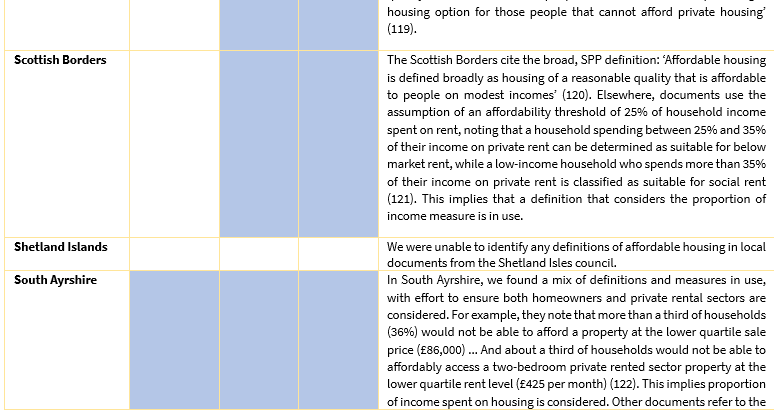

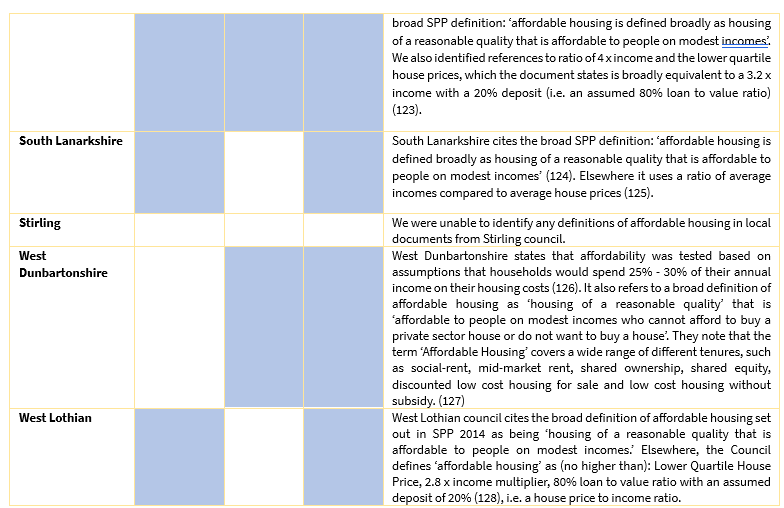

Part 2 provides an overview of the definitions that we were able to identify as in use at local authority level across Scotland. This information was not always easy to find and there are many examples in which councils, like the Scottish Government, refer to a broad definitions that do not specify how affordable housing should be measured. Where more specific measures are evident (e.g. in some Housing Needs and Demands Assessments), we find that councils are typically using one of the two most common measures identified in Part 1. Measures of affordability that better capture economic inequalities and the challenges facing low income households, such as residual income, are far less common.

If the ambitions of Housing to 2040 are to be realised, there needs to an agreed way of measuring affordable housing in Scotland to enable ongoing monitoring and evaluation. If affordable housing is, as the strategy suggests, designed to help reduce inequalities in Scotland, then this measure needs to work across tenure types (homeowners, people in social housing and private sector renters) and reflect the situation of the communities most in need (e.g. by incorporating a residual income element).

Introduction

Housing has long-been recognised as an important social determinant of health in Scotland (1); ‘affordable, warm housing which is free from damp’ (2) is widely accepted as central to improving public health and reducing health inequalities (3). The Scottish Government’s May 2024 declaration of a national housing emergency, and the 13 local authority declarations of housing emergencies, are therefore of concern from a health inequalities perspective. A recent Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee Housing Inquiry finding that a shortage of affordable homes, both for rent and for purchase, is a key driver of the housing emergency in Scotland.

Scotland already has an ambitious housing strategy, Housing to 2040, which aims to ensure that everyone in Scotland has access to a home that is affordable and choices about where they live. Yet, the term ‘affordable’ is used inconsistently when it comes to housing policy and practice in Scotland, often leading to confusion (4). The challenges that some people face in securing affordable housing can be obscured by average affordability indicators (5) and it can be hard to find measures that suit Scotland’s diverse local authorities. Yet, Scotland’s lack of an agreed way of measuring affordable housing means that it is hard to assess progress with official targets to create 110,000 affordable homes by 2032 (6, 7).

For now, there remains no single statutory definition of housing affordability in Scotland, leaving wide scope for variation at a local level. The Housing to 2040 strategy commits to ‘develop a shared understanding of affordability which is fit for the future’, and a working group, chaired by Professor Ken Gibb, is developing recommendations for the Scottish Government to consider when defining and measuring affordable housing. A letter from the Housing Minister to the convenor of the Scottish Parliament’s Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee noted that these recommendations would be shared with the Scottish Government ‘this Summer’ (9). Ahead of its publication, this SHERU briefing summarises measures of affordable housing that are in use internationally and compares these with the definitions we have identified in use locally in Scotland.

A key source is a 2018 UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) report, which sought to identify measures and definitions of affordable housing in use internationally (10). The CaCHE report compromises four ‘existing measures’ and two ‘new proposed measures’ (10). Part 1 of this SHERU briefing aims to provide an accessible overview of each of these measures, accompanied by examples of where each measure is in use, and key ‘pros’ and ‘cons’.

Part 2 of the briefing attempts to map how, in the absence of an agreed, measurable definition at the national level, Scotland’s 32 Local Authorities have been defining affordable housing in practice. This is important since many planning decisions sit at the local level. In this part of the briefing, we set out the definitions of affordable housing that we were able to identify in local policies and guidance documents. We focused particularly on Section 75 agreements (legally binding contracts between planning authorities and landowners which are often used to secure commitments to affordable housing) and Housing Needs and Demands Assessments (HNDAs) (see appendix).

Our analysis suggests that most local authorities in Scotland are currently employing broad definitions of housing affordability which do not explicitly outline measurement parameters. A common reference point is section 126 of Scottish Planning Policy, which defines affordable housing as, ‘housing of a reasonable quality that is affordable to people on modest incomes’ across a range of tenures (see this Scottish Government answer to a parliamentary question on this topic). Where local authorities do outline specific measures of housing affordability, they tend to use the ratio of average market property value to average incomes/earnings or a measure that compares a household’s income with their housing costs (see appendix). While the latter captures a wider range of tenures, neither is especially good at reflecting housing affordability for those on low incomes.

Assessing local definitions of affordable housing across Scotland has been challenging; there is a complex housing policy system and it is likely that further definitions are also in use in some settings. Nonetheless, we hope that Part 2 makes two useful contributions. First, it demonstrates the variability that currently exists at local level; this is the landscape into which any nationally agreed definition will emerge. Second, it shows that the most popular ways of measuring housing affordability in Scotland do not necessarily capture, or support a policy focus on, the situation facing the lowest income households. This raises questions about the extent to which current commitments to achieving affordable housing targets in Scotland will help tackle inequalities.

Part 1: Understanding Existing Measures

1. House price to income aka earnings ratio

A popular measure of how affordable housing is involves a simple ratio comparing the average price of houses to the average incomes or earnings of people living in the area. It is often presented by showing how many years of income it would take to buy a home – as in how many times a person annual salary a typical house would cost (10). In other words, 5 means the average house price is 5 times the average annual income. Internationally, this seems to the most widely used measure (4, 10). Higher ratios generally suggest housing is less affordable, though this does not capture the cost of capital, mortgage rates and interest rates. The ratio is easy to construct and intuitive to interpretate. This measure primarily focuses on the affordability of buying houses and is not effective at capturing housing affordability for people who rent (which, in Scotland, includes most households in the lowest income quintile, according to 2022 Fraser of Allander Institute analysis).

This measure generally looks at the median population as an indicator of costs, ratios, and proportions. Median price and income measures better reflect the economic impacts on middle-income households, as opposed to other averages, such as the mean, which are skewed upward by the inclusion of the highest incomes and prices (11, 12). Sometimes the lower quartile of house prices or incomes are used instead (12). In some cases, methods to calculate this use average earnings for people working in the area, rather than people resident in the area (4). This is done to avoid some gaps in annual earnings data at a constituency level. Regardless of the approach, this measure provides little sense of housing affordability for people who are in rented accommodation.

Where it is used:

· This is the most commonly used indicator in the UK, particularly in England and Wales and is widely used in many other countries (11), including the US, South Africa (13), Malaysia (14).

· In England and Wales, it is the measure used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and government to assess housing affordability (12). It is now included in the NPPF (National Planning Policy Framework) as part of the ‘standard method’ for determining housing need within a local planning authority in England and Wales (4). It is referenced in a range of UK governmental departments and policy-related documents (15, 16).

· In Scotland, this measure is used by many local authorities (see Part 2 of this briefing). This measure is referenced in most Housing Need and Demand Assessments (HNDAs). There are default settings for ‘percentile’ and ‘income ratio’ provided by the Centre for Housing Market Analysis, and the Glasgow Council’s Residential Housing Need and Demand Monitoring Project are content with this (17). Other housing related documents also reference this measure (see appendix)

· Widely used internationally by organisations like the United Nations, World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund, the Bank for International Settlements, national government ministries, financial institutions and other organisations to compare affordability across different cities and regions (18).

· Used by policy makers for example it can be used to identify areas with high housing costs relative to incomes, which can then inform policy decisions aimed at improving affordability (10). For example, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in England have both employed this measure.

· Mortgage lenders often use this measure to assess how much people can ‘afford’ and therefore borrow in the UK (19).

Pros:

· Easy to calculate and understand (10).

· Relatively easy to apply at an individual-level based on calculations you can do for your own household.

· Good for broad comparisons across different areas and over time (10) so can be used comparatively (20).

· Uses readily available data at a national level, which makes this a feasible measure to use for cross-country comparisons (10).

Cons:

· Overly simple – does not account for variations in income distribution (some people earn much more or much less than the average), different interest rates on mortgages, or the amount of savings people have for a deposit (10, 20).

· Provides no information on the distribution of outcomes across household types and income levels, such as for single-income households or joint-income households (10).

· Like other measures, does not assess the quality of housing that is being measured as affordable. This is important because poor quality housing is bad for health and costs occupiers (whether owners or renters) money in maintenance, utilities, etc (10, 21).

· Can be misleading as an indicator of changes in affordability over time (10) since it doesn’t account for factors like mortgage interest rates, down payment requirements, and property taxes (22).

· Rarely advocated by housing researchers because of its limitations in meaningfully capturing housing affordability as it is experienced by many residents (22).

· Not useful for understanding the affordability of the rental market for people in either the private renal sector or social housing because it primarily focuses on the affordability of buying a home, not renting one (10). This makes this measure unrepresentative of the lowest incomes households, who more typically rent (16).

· Difficult to target (impact or intervene) through policy; the ratio itself is a simplification of a multifaceted housing market influenced by factors like supply, demand, and government policies (10).

2. Proportion of income spent on housing or the housing cost to income ratio

This measure looks at what percentage (or proportion) of a household’s income goes towards housing costs (rent or mortgage payments, sometimes including utilities and property taxes). The common benchmark is the ‘30% rule,’ which suggests that housing is affordable if it costs no more than 30% of a household’s total monthly income (10). This is also known as a ‘ratio approach’ (23). In the UK, 35% of disposable income has traditionally been used as the threshold for affordability (24).

Low-income households who spend a high proportion of their income on housing may face conditions of housing stress. For example, there is evidence from England that low-income households with high housing expenditure ratios are more likely to face stress than those on high incomes (10).

Where it is used:

· This measure is also widely used internationally (10, 23), most notably in Australia (10) and also in New Zealand (25) and by mortgage lenders in Malaysia (14).

· While it is also used in the UK and Europe, it is often considered to be ‘an alternative measure’ (26), though it has been proposed as a new measure by the Affordable Housing Commission in England (20).

· Used by many local authorities in Scotland as part of Housing Need and Demand Assessments (see appendix)

· Think tanks such as The Resolution Foundation use this measure for research and reports on affordability (27, 28).

· Used when looking at private rental affordability in England and Wales by government and research institutions (30).

Pros:

· Familiar and widely used, simple and intuitive (10, 32).

· Relatively easy to understand and apply at an individual level based on calculations you can do for your own household.

· Directly relates housing costs to a household’s financial situation (10) and takes account of benefits received as part of income.

· Captures affordability for renters and home-owners (if they have a mortgage) (10, 33).

· Data is often available on income and housing costs at a broad level (10). The 30:40 indicator has been used long enough so that researchers and policy-makers can observe housing affordability stress trends over time (34).

· Can be used to make comparisons within local areas (such as cities) and across broader geographic areas (such as countries)(10).

· Provides an indication of the extent to which high housing costs may cause households financial stress (33).

Cons:

· Does not consider the absolute level of income or disposable income (30% of a very low income might still leave very little for other necessities) (10).

· Does not account for different household sizes or other essential living costs that can vary significantly, so does not account for whether residual income for housing costs is enough to live on (4). For example, 30% for a single person is different from 30% for a family with children (10). The ‘30%’ benchmark is somewhat arbitrary.

· Where it doesn’t include other housing costs, it ignores: council tax, maintenance charges, heating costs (i.e. efficiency) – all of which are policy intervention points.

· Depends on a normative judgement about what proportion of income should be spent on housing, despite evidence of variation by time, place, household type, life stage, etc (4, 27).

· Like other measures, does not assess the quality of housing that is being measured as affordable. This is important because poor quality housing is bad for health and costs occupiers (whether owners or renters) money in maintenance, utilities, etc (10, 21).

· Housing expenditures relative to income can appear more affordable than the reality for buyers due to restrictions on loans (e.g. it does not take into account credit market constraints, such as loan and deposit restrictions) and because it does not account for the quality and location of the property (10, 35).

· Reliable income data is not available for some small areas (including in Scotland), making it difficult for local actors to use this measure (4).

3. ‘Residual income’ for housing

Instead of looking at how much people spend on housing as a percentage of their income, this method asks: How much money do households have left after paying for housing? And is that enough to cover essential living costs? It subtracts the financial cost of a pre-defined standard of non-housing needs (e.g. food, transport, healthcare, energy) from disposable income, to assess how much money is left to spend on housing (e.g. rent or mortgage payments) (10). Unlike ratio-based methods, ‘residual income’ methods concentrate on the difference between incomes and housing costs rather than ratios. Housing often has first claim on people’s income, and if the amount paid for housing is unaffordable, the residual (or left over) income left for non-housing purposes will not be sufficient (10).

The focus is not just on spending, but on whether households can afford both housing and a decent standard of living. It is a very direct way to assess financial strain. It is often based upon a Minimum Income Standard (MIS) which represents the income that different households are believed to need to reach a minimum socially acceptable standard of living (4, 8). This can be understood in the UK to include, ‘more than just, food, clothes and shelter. It is about having what you need in order to have the opportunities and choices necessary to participate in society’ (36). Ratio approaches can be combined with residual income methods to construct a hybrid indicator (37).

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which works to promote an equitable and poverty-free society, uses a minimum income standard (MIS) to measure housing affordability, which is similar (though not exactly the same as) the residual income measure (38). The Josephe Rowntree Foundation’s MIS measure is considered in a recent Scottish Government Housing Affordability study (39). While a Scottish Government literature review on rent affordability, found that MIS to be foundational for new approaches in residual income measures (35). This is different from residual income measures because MIS defines the income needed for a socially acceptable standard of living, while residual income represents the money left over after essential expenses are covered.

Where it is used:

· Most relevant for analysing the affordability of housing for the poorest households (40); useful for measuring poverty (40).

· Used by policymakers particularly in relation to housing benefit allocations in places such as the UK and Austria (40, 41). For example, it is referenced by Scottish Government in a literature review as a potential improvement over ratio-based methods, particularly for low-income households (42) and also appears in research commissioned by the UK Government.

· Used by advocacy groups in the UK, such as Shelter (23, 43) and in UK-based research (36).

· Advocated by many housing researchers across diverse contexts, including Austria, Malaysia, India, the UK, US, and Australia (5, 41, 44).

Pros:

· Provides a more realistic picture of affordability than ratio measures for different household types and income levels by considering other essential expenses, so better reflects actual living conditions (10, 35).

· Can highlight affordability issues even when the percentage of income spent on housing is low, if the total income is also very low (8).

· Captures variations in household sizes and needs; accounts for some households having higher living costs e.g. families (10).

· Reveals hidden hardships – this approach shows that households could spend same proportion of income but with contrasting results in terms of poverty levels (45).

· Useful in guiding policy efforts to address inequalities and poverty.

Cons:

· More complex to calculate as it requires defining and estimating ‘essential’ non-housing costs, which can be subjective and vary across regions and households (though measures exist in the UK, such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Minimum Income Standard (38))

· More complex to communicate than simple ratios (10, 35).

· Does not take account of borrowing possibilities (10).

· Data on essential housing costs might not always be readily available. Requires detailed information on incomes, housing costs, and living costs, none of which are easily available at a local level.

· Like other measures, does not assess the quality of housing that is being measured as affordable. This is important because poor quality housing is bad for health and costs occupiers (whether owners or renters) money in maintenance, utilities, etc (10, 21).

· Not standard practice in many countries, making international comparisons harder (10).

4. Incorporating supply

The CaCHE report (10) notes that measures can be made to incorporate both demand and supply elements such as through attempting to relate the number of housing units potentially affordable by different income groups to the total number of households in each income group. This approach looks at housing affordability in the context of availability of housing, especially whether there is enough supply to meet demand. The idea is that lack of supply is a root cause of affordability problems. It links affordability outcomes (like high prices and rents) directly to shortages in housing provision, offering a broader view of market pressures. Low vacancy rates usually indicate high demand and limited supply, often driving up prices and making housing less affordable. It is not a direct measure of housing affordability but examining vacancy rates, or comparing the distribution of available housing by costs with the distribution of household incomes, can provide some sense of the number of housing units potentially affordable by different income groups compared to the total number of households in each income group. Rather than just looking at prices or rents, this measure considers: the balance of supply and demand (e.g. new homes built versus household growth); vacancy rates; and pressure on existing stock, which can drive up costs even if incomes stay the same. It helps focus policy attention on building more homes, rather than on managing the cost of housing.

Where it is used:

· In England, the National Planning Policy Framework incorporates a baseline of local housing stock which is then adjusted upwards to reflect local affordability pressures to identify the minimum number of homes expected to be planned for (49).

· In Scotland, this information is considered in the Affordable Housing Supply Programme (50, 51).

Pros:

· Provides a market-level perspective on affordability pressures which gives more attention to the supply of homes available to the lowest income groups, including those in the private rental sector and in social housing (52).

· Acknowledges that availability of housing is a crucial factor in housing affordability (10).

· Data on vacancy rates are often collected and publicly available.

· Measures can be built to reflect the balance between available housing units and the number of households that can afford them. This approach helps determine how many households can potentially afford housing within the available stock (10).

· Helps highlight important regional differences since areas with housing shortages often have the worst affordability (10).

· Frames housing affordability as part of wider housing system market dynamics (10).

Cons:

· This approach does not directly measure housing affordability (10) so is only an indirect indicator of potential housing affordability, which is likely to be influenced by many factors beyond just affordability (e.g., economic growth, migration). It is therefore best used alongside other measures, especially since adding supply does not guarantee lowered prices if demand remains high (10).

· Difficult to measure accurately; true housing need and future demand is complicated (10). There is no single, universally accepted method for measuring housing supply. Measurements tend to be in relation to number of dwellings rather than bedrooms or quality of housing (53-55).

· Risk of oversimplification – supply focus can overshadow other important factors such as income inequality, credit conditions, quality/ standard of housing, and investor demand (10).

· Not widely used internationally; comparisons are harder to make (10).

New Proposed Measures

Low-income renter affordability

This measure focuses on how affordable rents (in private rental and social housing sectors) are for people on lower incomes, typically those in the bottom 20% or 40% of the income distribution. A spending measure, weighted by the income quintile (poorest 20%, 40% etc.), is more appropriate when exploring low-income renter affordability (10). For example, those in the bottom income 20% who are spending more than 25% of their incomes on housing costs are twice as likely to face stress as those in the top 20%. The goal is to understand affordability specifically for people who are most at risk of housing stress and exclusion.

Where it is used:

· Noted in the Scottish Government literature review on rent affordability (35).

· The OECD has rankings for low-income rental affordability (56), which enables international comparison.

· Informs some social housing affordability measures in Scotland (57).

Pros:

· Focuses on those most affected by affordability; targets the experiences of vulnerable households (10).

· Monitors a portion of the market in which policy might most easily intervene with current levers (e.g. housing-related benefits and social housing supply).

· Helps focus policy attention on improving affordability for low-income renters, who include many households in the lowest income quintile in Scotland.

· Can be used to track trends in poverty and housing exclusion over time.

Cons:

· Requires accurate information on both low incomes and rents, which are not always available at local levels (10).

· Like other measures, does not assess the quality of housing that is being measured as affordable. This is important because poor quality housing is bad for health and costs occupiers (whether owners or renters) money in maintenance, utilities, etc (10, 21).

· Renter focused; does not capture housing market pressure, particularly for first time buyers.

First-time buyer affordability

This measure looks specifically at how affordable it is for people to buy their first home. It usually compares house prices of first homes (often median prices for starter homes) to incomes (often median incomes of younger households or first-time buyer households). It focuses on entry to homeownership, rather than overall housing costs. This measure aims to show whether people who do not already own a home can realistically afford to buy one – an important signal for social mobility and access to homeownership. This approach often underlies Help to Buy schemes. Multiple versions of this measures have been used in by the UK Office for National Statistics (58). When considering first-time buyer affordability one must consider purchase affordability (whether the household is able to borrow sufficiently to buy a house) and repayment affordability (which considers the proportion of income spent on servicing the mortgage) (10, 59).

The CaCHE report provides some illustrative examples for first-time buyers. Assuming a 5% mortgage rate, a 5% deposit and a 25-year mortgage, it shows that the bottom 60% of the income decile would have to spend more than 30% of their income to purchase any property in the Southeast of England. In the Northeast, the bottom 30% of the income distribution would not be able to buy a home without spending more than 30% of their income.

Where it is used:

· Reflected in ‘help to buy’ schemes in the UK (60)

Pros:

· Focuses on a critical life stage for many people: buying first home (10, 58).

· Recognises the importance of variations in the availability of different types of property (10).

· Good for tracking market trends, including regional analysis (10, 58).

Cons:

· Overly simple; first time buyers have varying levels of income, saving, and support (10). Does not capture credit availability and tighter lending standards (10). Ignores other factors (e.g. deposits, mortgage rates and legal fees).

· There are considerable differences in conditions (both in terms of the housing market and credit availability) around the country and internationally.

· Assumes home ownership is the goal of affordable housing policy.

· In some cases only an indication of an individual’s affordability and so does not apply to those who purchase a property with other people (58).

· Excludes affordability for renters (10).

· Like other measures, does not assess the quality of housing that is being measured as affordable. This is important because poor quality housing is bad for health and costs occupiers (whether owners or renters) money in maintenance, utilities, etc (10, 21).

· Misses wider financial pressures that are acknowledged in residual income measures.

· Focuses on a particular group; misses most younger and older households (10, 58).

· Quality of housing not included; may show affordability even in poor quality or inadequate housing (10).

Defining and measuring housing affordability in Scotland

Alongside the declared national housing emergency, 13 of Scotland’s 32 local authorities have declared local housing emergencies, beginning with Argyll and Bute in June 2023 (66). Homelessness charities and NGOs such as Shelter Scotland also describe the current situation in multiple areas of Scotland, including the two largest cities – Glasgow and Edinburgh – as an emergency (6, 7). Affordability pressures are playing a key role in this challenging context, and the resulting experiences of poor quality homes and homelessness are not only harming health and wellbeing but also generating significant fiscal pressures, with many councils reporting rising costs for temporary housing provision. (61). Progress with affordable housing is therefore an urgent task, as the Scottish Government has recognised via Housing to 2040 and the Affordable Housing Supply Programme, which aims to deliver 110,000 affordable homes by 2032, with a focus on social rent and rural communities (51, 67). Yet, as we outlined in the Introduction, there is no single standard definition of affordable housing or measure of housing affordability in Scotland (63).

In the second part of this briefing, we focus on definitions in use in Scotland. We start by noting that, in public evidence on 16 April 2024, the Minister for Housing was clear that ‘we do not actually have a definition of what [affordable housing] is’ (64). A report by Audit Scotland (65) confirms that Scotland takes a local approach to defining housing affordability, which could be argued to be appropriate in terms of reflecting variations in the local context. However, as already noted, this makes it hard to assess Scottish Government progress with meeting official commitments to growing affordable housing, as well as contributing to public and stakeholder confusion.

Examples of definitions nationally include the Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) definition, noted earlier, and the National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) definition of: ‘good quality homes that are affordable to people on low incomes’. While the Affordable Housing Supply Programme focuses on social rent, mid-market rent and low-cost home ownership, the NPF4 defintion is slightly broader, applying to ‘social rented, mid-market rented, shared-ownership, shared-equity, housing sold at discount (including plots for self-build), self-build plots and low cost housing without subsidy.’ (68).

At a local level, councils often need to provide more specific definitions. For example, in Section 75 Agreements, which are typically used to clarify conditions for new housing developments, councils need to be clear to housing developers who they are requiring to include affordable housing what they will class as affordable (69). Another example is the Housing Need and Demand Assessment (HNDA) tool, which is used by the Scottish Government to help local authorities assess housing needs and demand in their areas. It plays a key role in informing local housing strategies and local development plans. The HNDA provides evidence for decisions related to housing, homelessness, and the provision of specialist accommodation (70). Our work to map definitions of affordable housing in use locally suggest this is often the document that provides most insight into measures and definitions, alongside local housing strategies, local development plans, and briefings.

How affordable housing is being defined locally in Scotland

Most councils do not explicitly articulate how they measure affordable housing but it can often be inferred from local policy documents and HNDAs. However, even in these documents, councils sometimes evade concrete definitions by referencing the ambiguous and broad national definitions (see above). The table provided in the Appendix summarises in greater detail how different Scottish Local Authorities define affordable housing, according to our analysis of local policy documents.

The most commonly cited national definition comes from the SPP which, as noted earlier, describes affordable housing as, ‘housing of a reasonable quality that is affordable to people on modest incomes.’ (71). This is followed in incidence by the definition found in the NPF4, which refers to ‘good quality homes that are affordable to people on low incomes’ (68). The variation in language – particularly the use of ‘reasonable’ in the SPP and ‘good’ in the NPF4 – suggests a subtle but important difference in emphasis, with NPF4 hinting at a more holistic and optimistic understanding of the housing experience in terms of quality and affordability.

Beyond national definitions, local authorities’ HNDAs also reflect differing levels of clarity and detail. Councils including Dundee City, Orkney Islands, and Falkirk include a broader, economically contextualised definition, describing housing affordability as encompassing ‘income, house prices, rent levels, access to finance and key drivers of the local and national economy.’ (72-74). However, many local planning documents do not provide an explicit definition of affordable housing or detail how affordability is measured. Some councils, like Moray, offer clear and concise definitions about how their council defines affordability in their document titled ‘What is ‘Affordable’ in the Moray Context’ (75), or Clackmannanshire Council’s Housing Revenue Account Business Plan & Capacity Review which offers a range affordability measures (76). While others, such as Aberdeen City, adhere closely to the more general Scottish policy definitions with little (if any) elaboration on measures of affordability such as those explored in this report.

HNDAs are designed to give broad, long-run estimates of what future housing need might be, rather than precision estimates. They provide an evidence-base to inform housing policy decisions in Local Housing Strategy (LHS) and land allocation decisions in Local Development Plans (70). The HNDAs conducted for the local authorities broadly define affordable housing based on whether households can afford to access market housing (rented or owned) without subsidy (e.g. housing benefit or housing allowance). A housing consultancy firm, Arneil Johnston, was commissioned to deliver a Housing Need & Demand Assessment for many Scottish local authorities. According to their website, over the last 28 years, they have worked with every local authority in Scotland (77).

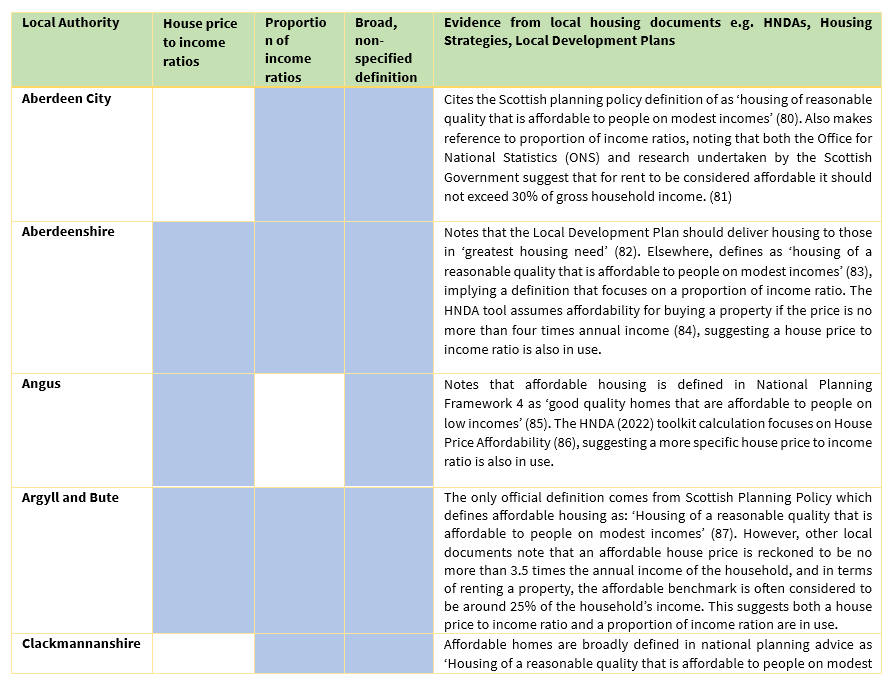

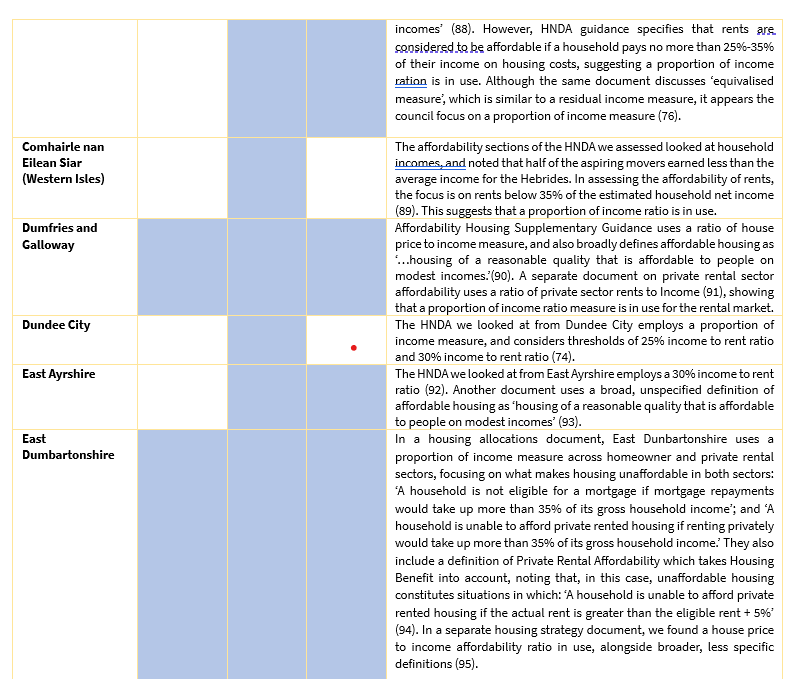

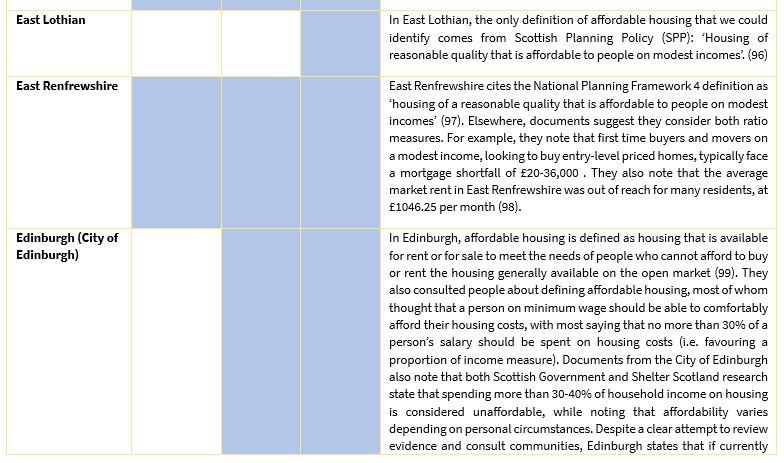

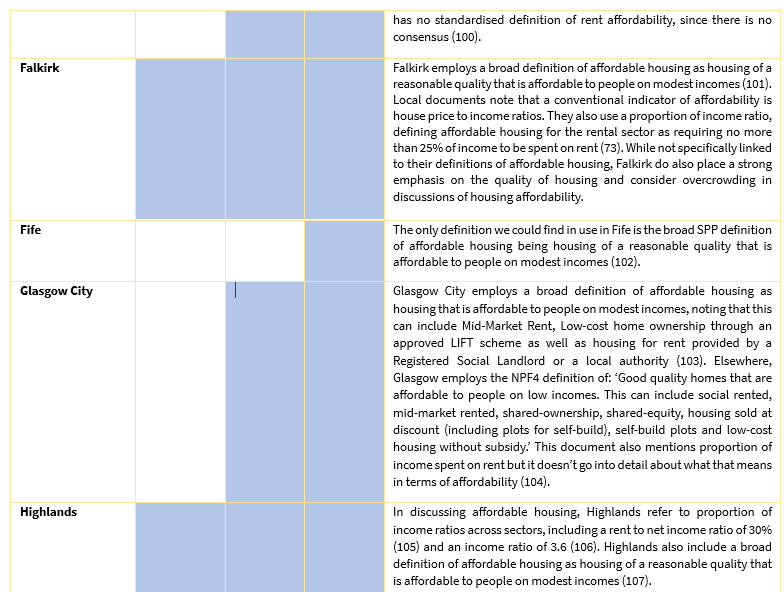

In many local housing documents, the terms affordable and affordability were used without providing a specific definition or measure. West Dumbartonshire, for example, provide a helpful glossary in their housing strategy report but it does not include affordable or affordability (78). Nonetheless, for most Local Authorities, we were able to identify at least some definitions. Most commonly, we found broad, non-specific definitions that reflected national definitions. Beyond this, our findings (summarised in Table 1) show that most local authorities in Scotland utilise one or both of the two most common international measures: house price to income ratio and/or a proportion of income spent on housing. Some councils employ both measures, often using the house price to income ratio to capture affordability for house purchaser/homeowners, and a proportion of income measure to capture affordability for private sector renters. Where measures focused on the proportion of income spent on housing, several councils suggested specific thresholds of between 25% and 35% of income. In many cases, perhaps because social housing is already heavily regulated, social housing was not included in measures. Other council documents refer to ratios but do not clarify the parameters. There are less common mentions of residual income.

Table 1: Table showing approaches to housing affordability measures of Scottish Local Authorities

The documentation surrounding affordable housing is complex and we may well have missed additional definitions in use in some local contexts. However, our findings are sufficient to conclude that definitions of affordable housing in use locally in Scotland are: (1) dominated by measures that do not capture the situation facing the lowest income households; and (2) rarely linked to definitions of what is deemed to constitute reasonable or good quality housing (76). This underlines a sense that current approaches to affordable housing in Scotland are disconnected from efforts to assess and improve housing quality. This is important from the perspective of health inequalities since homes that benefit (or at least, do not harm) people’s health need not only to be affordable but also to to be of decent quality (e.g. warm, dry, mould and pest-free).

Summary

There are multiple ways of defining affordable housing and Scotland does not currently have an agreed national definition, despite the fact Housing to 2040, the Scottish Government’s national housing strategy, includes specific targets for affordable housing. In this briefing, we reviewed common definitions of affordable housing (10), considering the pros and cons of each. Simpler methods like ratio measures are useful for broad comparisons and relatively easy to calculate, which makes them popular. However, some measures exclude key low-income groups, such as renters or those in social housing. More sophisticated approaches, such as the residual income measure, provide a deeper understanding but are more challenging to track. There may, therefore, be merit in combining elements from different measures. If affordable housing is, as the strategy suggests, designed to help reduce inequalities in Scotland, then this measure needs to work across tenure types (homeowners, people in social housing and private sector renters) and reflect the situation of the communities most in need (e.g. by incorporating a residual income element).

In the absence of an agreed national definition, and in the context of substantial contextual variation, it is unsurprising that local areas in Scotland have adopted contrasting definitions of affordable housing (see Appendix). This does, however, raise questions about how to track and assess policy commitments to expanding affordable housing. Additionally, it seems that many of the most popular measures may not be focusing policy attention on the lowest income households. In the coming year, SHERU will be exploring local approaches to affordable housing commitments, and community views about this, in our ongoing Strengthening Policy Implementation work. Our focus will be on the people facing the greatest challenges when it comes to health and housing.

References

1. Walsh D, McCartney G, Collins C, Taulbut M, Batty GD. History, politics and vulnerability: explaining excess mortality in Scotland and Glasgow. Public health. 2017;151:1-12.

2. Greater Glasgow Health Board. THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC HEALTH 1992/93 Glasgow; 1995.

3. Best R, editor Health inequalities, the place of housing. Inequalities in health: the evidence presented to the Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health, chaired by Sir Donald Acheson; 1999.

4. Wilson W, Barton C. What is affordable housing? . House of Commons Library; 2023.

5. Stone ME, Burke T, Ralston L. The residual income method: a new lens on housing affordability and market behaviour. 2011.

6. Shelter Scotland. 2024. [21/05/25]. Available from: https://scotland.shelter.org.uk/campaigning/what_is_the_housing_emergency.

7. COSLA. Scotland’s Housing Emergency. 2024.

8. Marshall L. 2016. [21/05/25]. Available from: https://www.housing-studies-association.org/articles/98-defining-and-measuring-housing-affordability-in-the-prs-using-the-minimum-income-standard.

9. Scottish Government. Housing to 2040 and building safety: Correspondence to the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee. 2024.

10. Meen G. How should housing affordability be measured. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence; 2018.

11. Cox W. Demographia International Housing Affordability 2024. Center for Demographics and Policy; 2024.

12. ONS. Housing affordability in England and Wales: 2024. In: team HA, editor. 2025.

13. Mmesi L. A comparative study of housing affordability in South Africa using the adjusted Debt-Service Ratio and Price-Income Approach: University of the Witwatersrand; 2021.

14. Subramaniam GK, Zaidi MAS, Karim ZA, Said FF. Constructing Housing Affordability Index in Malaysia. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia. 2024;58(1):20-39.

15. UK Government. Official statistics: rural housing. 2022.

16. Hilber C, Schöni O. Housing policy and affordable housing. Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political …; 2022.

17. Glasgow City Region Housing Market Partnership. Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Housing Need and Demand Assessment. Glasgow; 2024.

18. Cox W. A question of values: Middle-income housing affordability and urban containment policy. Frontier Centre for Public Policy; 2015.

19. ONS. Housing purchase affordability, UK, QMI. 2023.

20. Affordable Housing Commission. A report by the Affordable Housing Commission-Defining and measuring housing affordability – an alternative approach. 2019.

21. Bramley G. Affordability, poverty and housing need: triangulating measures and standards. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. 2012;27(2):133-51.

22. Svensson LE. Are Swedish house prices too high? Why the price-to-income ratio is a misleading indicator. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2023.

23. Rao PK, Biswas A, editors. Measuring housing affordability using residual income method for million-plus cities in India. Proceedings of the International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism-ICCAUA; 2021.

24. Reynolds L. Shelter Private Rent Watch. Report 1: Analysis of local rent levels and affordability London: Shelter. 2011.

25. Biljanovska N, Fu MC, Igan MDO. Housing affordability: A new dataset: International Monetary Fund; 2023.

26. ONS. Research Output: Alternative measures of housing affordability: financial year ending 2018. 2020.

27. Clarke S, Corlett A, Judge L. The Housing Headwind: the impact of rising housing costs on UK living standards. Resolution Foundation; 2016.

28. Corlett A, Judge L. HOME AFFRONT Housing across the generations. Resolution Foundation; 2017.

29. Corlett A, Judge L. The Resolution Foundation Housing Outlook Q1 2024. The Resolution Foundation; 2024.

30. ONS. Private rental affordability, England and Wales: 2023. 2024.

31. Waters T, Wernham T. Housing quality and affordability for lower-income households. Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2023.

32. UK Government. Chapter 2: Housing costs and affordability. 2023.

33. UK Government. English Housing Survey 2023 to 2024: Experiences of the ‘housing crisis’. 2025.

34. AHURI. Understanding the 30:40 indicator of housing affordability stress 2019 [Available from: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/analysis/brief/understanding-3040-indicator-housing-affordability-stress.

35. Scottish Government. Rent affordability in the affordable housing sector: literature review. 2019.

36. Padley M, Marshall L. Defining and measuring housing affordability using the Minimum Income Standard, and the possibility of a living rent 2016.

37. Bramley G, Karley NK. How much extra affordable housing is needed in England? Housing Studies. 2005;20(5):685-715.

38. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. A Minimum Income Standard for the United Kingdom in 2022. 2022.

39. Scottish Government. Housing affordability study: Findings report. 2024.

40. Whitehead C, Monk S, Clarke A, Holmans A, Markkanen S. Measuring Housing Affordability: A Review of Data Sources. Cambridge: Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research; 2008.

41. Mundt A. Housing benefits and minimum income schemes in Austria – an application of the residual income approach to housing affordability of welfare recipients. International Journal of Housing Policy. 2018;18(3):383-411.

42. Scottish Government. Housing affordability study: Findings report. 2024.

43. Shelter UK. Costs and affordability of accommodation 2024 [Available from: https://england.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/legal/homelessness_applications/suitability_of_accommodation_for_homeless_applicants/costs_and_affordability_of_accommodation.

44. Sohaimi NS, Abdullah A, Shuid S. Determining housing affordability for young professionals in klang valley, Malaysia: Residual income approach. Planning Malaysia. 2018;16.

45. Stephen Ezennia I, Hoskara SO. Methodological weaknesses in the measurement approaches and concept of housing affordability used in housing research: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221246.

46. UNECE. Challenges and priorities for improving housing affordability in the UNECE region. New York, NY: United Nations Publications; 2025.

47. Stephens M, Van Steen G. ‘Housing poverty’and income poverty in England and the Netherlands. Housing Studies. 2011;26(7-8):1035-57.

48. Haffner M, and Heylen K. User Costs and Housing Expenses. Towards a more Comprehensive Approach to Affordability. Housing Studies. 2011;26(04):593-614.

49. UK Government. Housing and economic needs assessment 2025 [Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/housing-and-economic-development-needs-assessments#:~:text=An%20affordability%20adjustment%20is%20applied,address%20the%20affordability%20of%20homes.

50. Scottish Government. The delivery of the affordable housing supply programme 2022 [Available from: https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/committees/current-and-previous-committees/session-6-local-government-housing-and-planning/business-items/housing-to-2040-and-housing-emergency/the-delivery-of-the-affordable-housing-supply-programme#:~:text=The%20Affordable%20Housing%20Supply%20Programme%20(AHSP)%20comprises%20a%20range%20of,local%20authorities’%20Local%20Housing%20Strategies.

51. Scottish Parliament. Affordable Housing Supply Programme. 2025.

52. Kepili EIZ. Examining the relationship between foreign purchase liberalisation and housing affordability. International Journal of Property Sciences (E-ISSN: 2229-8568). 2020;10(1):26-38.

53. UK Government. Housing supply: net additional dwellings. 2024.

54. Rankl F, Barton C. Calculating housing need in the planning system (England). 2024.

55. Scottish Government. Housing Statistics 2024: Key Trends Summary. 2025.

56. Waite G. Resetting Benefits: benchmarks for adequate minimum incomes. Policy Quarterly. 2021;17(4):58-64.

57. East Ayrshire Council. Housing Need and Demand Assessment. East Ayrshire; 2018.

58. ONS. First-time buyer housing affordability in England and Wales: 2017. 2018.

59. Gan Q, Hill RJ. Measuring housing affordability: Looking beyond the median. Journal of Housing economics. 2009;18(2):115-25.

60. UK Government. Affordable home ownership schemes 2025 [Available from: https://www.gov.uk/affordable-home-ownership-schemes.

61. The Herald. Scotland spends £720m in putting homeless in housing limbo. 2024.

62. Scotland’s Census. Scotland’s Census 2022- Housing. 2022.

63. Argyll & Bute Council. Housing Need & Demand Assessment Technical Supporting Paper 04 Core Output 1: The Local Housing Market and Affordability in Argyll & Bute, 2020. Argyll & Bute; 2021.

64. Scottish Parliament. Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee Official Report. 2024.

65. Audit Scotland. Affordable housing: The Scottish Government’s affordable housing supply target. 2020.

66. Scottish Parliament. Housing emergency. 2025.

67. Scottish Government. More Homes. 2025.

68. Scottish Government. National Planning Framework 4. 2024.

69. North Lanarkshire Council. Apply for planning permission. 2025.

70. Moray Council. Moray Housing Market Partnership Housing Need & Demand Assessment Final Report. Moray; 2023.

71. Scottish Government. Planning Advice Note 2/2010: Affordable Housing and Housing Land Audits. 2010.

72. Orkney Islands Council. Housing Needs and Demands Assessment 2023. 2023.

73. Falkirk Council. Housing Needs and Demands Assessment 2022. 2022.

74. Dundee City Council. Housing Need & Demand Assessment Final Report. Dundee; 2022.

75. Moray Council. What is ‘Affordable’ in the Moray Context. nd.

76. Clackmannanshire Council. 2023 HRA Business Plan and Capacity Review Assignment Review 1: Rent Affordability. 2023.

77. Arneil Johnston. About Arneil Johnston nd [Available from: https://www.arneil-johnston.com/.

78. West Dumbartonshire Council. Local Housing Strategy 2022 – 2027. 2022.

79. Scottish Parliament. Evolving Goals: Insights into the National Performance Framework Review 2024.

80. NHS Grampian. HIALHS Workshop Report. 2018.

81. Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council. Housing Need & Demand Assessment 3: 2023 – 2028. 2023.

82. Aberdeenshire Council. Review of Policy 6: Affordable Housing 2013.

83. Aberdeenshire Council. Review of SG Affordable Housing 1: Affordable Housing 2013.

84. Aberdeenshire Council. Aberdeenshire Council Local Housing Strategy 2024 – 2029. 2024.

85. Angus Council. Affordable housing contributions. nd.

86. Angus Council. Appendix 3b: Refresh of the Housing Need and Demand Assessment. 2023.

87. Argyll & Bute Council. ARGYLL and BUTE STRATEGIC HOUSING INVESTMENT PLAN 2024/25 – 2028/29 2024.

88. Clackmannanshire Council. SUPPLEMENTARY GUIDANCE 5 AFFORDABLE HOUSING

2015.

89. Hebridean Housing. OUTER HEBRIDES HOUSING NEEDS AND DEMAND ASSESSMENT SURVEY REPORT. 2021.

90. Dumfries and Galloway Council. LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 Affordable Housing Supplementary Guidance. 2020.

91. Dumfries and Galloway Council. Housing Need and Demand Assessment August 2016. 2016.

92. East Ayreshire Council. East Ayrshire Council Local Housing Strategy 2025 – 2030. 2025.

93. East Ayreshire Council. East Ayrshire Local Development Plan 2 Housing Land Audit 2022 Volume 1: Summary Report. 2022.

94. East Dunbartonshire Council. Housing Allocations Policy. nd.

95. East Dunbartonshire Council. Local Housing Strategy 2023–2028. 2023.

96. East Lothian Council. Supplementary Planning Guidance: Affordable Housing February 2019. 2019.

97. East Renfrewshire. Supplementary Guidance: Affordable Housing. 2023.

98. East Renfrewshire. East Renfrewshire Local Housing Strategy 2024-29. 2024.

99. The City of Ediburgh Council. Affordable Housing Health, Social Care and Housing Committee. 2007.

100. The City of Ediburgh Council. Housing, Homelessness and Fair Work Committee: Edinburgh’s Local Housing Strategy – Draft Strategy 2025.

101. Falkirk Council. SG06 Affordable Housing. 2021.

102. Fife Council. Affordable Housing Supplementary Guidance September 2018. 2018.

103. Glasgow City Council. GLASGOW’S AFFORDABLE HOUSING SUPPLY PROGRAMME PERFORMANCE REVIEW 2021/22. 2022.

104. Glasgow City Council. Glasgow City Council City Development Plan 2 Evidence Report: Housing March 2024. 2024.

105. Bramley G, Watkins D. Highland’s Housing Need & Demand Assessment Appendix A HIGHLAND HOUSING NEED AND AFFORDABILITY MODEL REPORT 2009.

106. Highland Council. HIGHLAND COUNCIL HOUSING NEED AND DEMAND ASSESSMENT 2020. 2021.

107. Highland Council. Supplementary Guidance: Developer Contributions. 2013.

108. Inverclyde Council. Rapid Rehousing Transition Plan 2020.

109. Inverclyde Council. INVERCLYDE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2014 SUPPLEMENTARY GUIDANCE on AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROVISION. 2014.

110. Midlothian Council. Supplementary Planning Guidance AFFORDABLE HOUSING. 2012.

111. Midlothian Council. Local Housing Strategy 2021-2026. 2021.

112. North Ayrshire Council. Adopted Local Development Plan: Your Plan Your Future. 2019.

113. North Ayrshire Council. Locality Profile Three Towns. 2017.

114. North Lanarkshire Council. LOCAL HOUSING STRATEGY 2021-26. 2021.

115. Perth and Kinross Council. Developer Contributions and Affordable Housing. 2016.

116. Perth and Kinross Council. Elected Member Briefing – Affordable Housing Overview. 2022.

117. Renfrewshire Council. Renfrewshire Strategic Housing Investment Plan 2025 to 2030. 2025.

118. Renfrewshire Council. Renfrewshire Local Housing Strategy 2023-2028. 2023.

119. Renfrewshire Council. Renfrewshire Local Development Plan Main Issues Report 2017. 2017.

120. Scottish Borders Council. Scottish Borders Local Plan Supplementary Guidance on Affordable Housing Updated and Revised. 2015.

121. Scottish Borders Council. Local Housing Strategy (LHS) 2023-28 Evidence Paper 2023.

122. South Ayrshire Council. Local Housing Strategy 2023 – 2028. 2023.

123. South Ayrshire Council. South Ayrshire Housing Need and Demand Assessment 2021-2026 Consultative draft July 2021. 2021.

124. South Lanarkshire Council. South Lanarkshire Local Development Plan Supplementary Guidance 7.

125. South Lanarkshire Council. South Lanarkshire Local Housing Strategy 2022-27. 2022.

126. West Dumbartonshire Council. LOCAL HOUSING STRATEGY 2017 – 2022. 2017.

127. West Dumbartonshire Council. WEST DUNBARTONSHIRE Local Development Plan 2 Main Issues Report. 2017.

128. West Lothian Council. Affordable Housing. 2025.

Citation

Ljubojevic, Maya; with input from Katherine E. Smith (2025) International Definitions and Measures of ‘Affordable Housing’ and Current Local Practices in Scotland. Glasgow: Scottish Health Equity Research Unit.

Appendix: Table showing the 32 Scottish local authorities and our assessment of how they define or measure housing affordability